Since Akira Kurosawa’s groundbreaking movie, Rashomon (1950), introduced Japanese cinema to the Western world, the Western film critics’ processes of discovery and evaluation of the Japan’s greatest directorial talents have constantly been both ideologically cloaked and selective.

First, humanist critics like Donald Richie hailed filmmakers who demonstrated a unique style and whose work supported a strong humanist attitude. Meanwhile, Richie dismissed directors he considered to be mere producers of commercial films—solid craftsmen at best.

This critical standpoint was then picked up by French critics, such as members of the infamous Cahiers du Cinéma, who applied their Auteur theory to the Japanese cinema. Subsequently, the Cahiers du Cinéma celebrated the Japanese masters who had a unified style and content in their bodies of work, but the French critics condemned more diverse directors.

The consequences of this rather limited perception of Japanese cinema continues to haunt the work of every new Japanese film writer. To this day, ridiculously narrow-minded critics and scholars thoughtlessly name, adopt, and redistribute renowned directors Akira Kurosawa, Kenji Mizoguchi, and Yasujiro Ozu as “The Big Three of Japan’s Golden Age of Cinema.”

Japanese genre directors are largely dismissed by film critics, and Japanese film criticism as a whole emerges as a confined space in which the work of “auteurs”—such as Kurosawa and Ozu—receive the most attention and often prolific, in-depth analyses. Many other great masters of Japanese cinema, however, still linger in the shadows of obscurity.

Nevertheless, the advent of the home video in the 1980s slowly changed the Japanese cinematic situation. Curious, young students of Japanese cinema, as well as often devoted fans or projectionists, began to rediscover the great Japanese genre cinema of the 1960s and 1970s. The arrival of the home video also gave talented studio artisans, like Kenji Misumi or Kinji Fukasaku, the attention their impressive bodies of work well deserved.

This list tries to go one step further and present ten great Japanese directors whose work, until recently, has received little-to-no attention in the West. As with most top ten film lists, the choices of the respective directors are meant to be nothing more than representative.

Since this list focuses primarily on directors who had their directorial prime in the 1950s and 1960s, few of the great directors of pre-war or modern Japanese cinema are included. Needless to say, many more brilliant Japanese directors that are to be rediscovered do exist. In times of globalization and the internet, this rediscovery doesn’t rest solely in the hands of Japanese film scholars anymore.

In this respect, this list should serve as an inspiration for every film fan to look beyond the well-known names of Japanese cinema. After all, one fan reading this list can be the individual to discover the next great, forgotten director of Japanese cinema and reevaluate his or her work for the public.

10. Toshio Masuda (1927 – now)

Despite the fact that Toshio Masuda was one of the most commercially successful directors of the famous production company, Nikkatsu, his work is doomed to exist behind the shadow of his more famous colleague, Seijun Suzuki. The reason for this is Suzuki’s alleged rebel status and extraordinary style.

He is said to have enriched the typical gangster films of his studio with his attitude and style, which, when made by other contract directors, normally were unoriginal and dull. Moreover, the trademark coolness and outlandish 1960s stylization of Suzuki’s films were highly influenced by Nikkatsu’s studio policy. A fact often forgotten by Western critics. Yet Masuda, who had an integral part in shaping the style of Nikkatsu’s typical company product, is often overlooked.

During his time as a contract director for Nikkatsu, Masuda specialized in a genre called mukokuseki akushon (borderless action). Set in contemporary Japan, these films strived for a more international style in which the main characters were usually former boxers and cops, drove in fancy modern cars, and drank their whiskey in Westernized nightclubs (instead of traditional Japanese inns).

Already his third film in the genre, Masuda managed to direct one of the highest grossing films of the year, the highly atmospheric Rusty Knife (Sabita naifu, 1958). In the following decade, he established himself as one of the studios top directors who, in contrast to Seijun Suzuki, was allowed to make films with Nikkatsu’s biggest star, Yujiro Ishihara.

Often those films, concentrating more on atmosphere than character or story, were fairly trivial affairs. However, when Nikkatsu Action films adopted a more somber tone in the late 1960s, it was also Toshio Masuda who directed two of the greatest masterpieces of that era: Velvet Hustler (Kurenai no nagareboshi, 1967) and Gangster VIP (Borai yori: Daikanbu, 1969).

Contrary to Suzuki, Masuda never allowed the visual excess reign over the content of his films. Thus, while his films were not as visually striking as Suzuki’s, they usually were much more emotionally arresting and visually united.

For example, Velvet Hustler is modeled slightly after Godard’s Breathless (1959). The film—with the eternal coolness and air of melancholy of its main protagonist; the laid back atmosphere, and the excellent low-key jazz soundtrack—reveals itself as one of the greatest works to embody the tone of the Swinging Sixties.

Gangster VIP (1969), on the other hand, is actually a hybrid gangster film which effectively juxtaposes the international atmosphere of the classical Nikkatsu Action film with the honorable and pathos-filled ninkyo eiga-type yakuza films that the Toei Company made at that time.

Even after Nikkatsu switched to pornography in the 1970s, Masuda continued to helm often highly successful big-budget blockbusters for other studios.

While those films were highly restricted by studio requirements and the general decline of the Japanese film industry, at least during his time at Nikkatsu´s production facilities, he made some of the most perfect modern and hip gangster films to ever graze the Japanese silver screens. For this alone, he deserves to stand shoulder to shoulder next to his critically acclaimed contemporary, Seijun Suzuki.

9. Masahiro Makino (1908 – 1993)

Without exaggeration, Masahiro Makino is one of the most prolific directors of all-time. In his forty-six years as a director, he made no less than 261 films—most of them feature length. Why, then, are his achievements largely neglected by the critics? Makino is regarded as a hack by the few who know him.

He is seen as a craftsman who filmed fast, but whose films were barely more than routine programmers. Often forgotten, however, is (at least in the earlier part of his career) that he created some of the most influential jidai-geki ever made.

The son of famous Japanese film pioneer Shozo Makino, Masahiro Makino began directing period pieces in 1926 for his father’s production company. He rose to fame when he made grim samurai spectacles like his Roningai series (1928-1929) and Beheading Place (Kubi no za, 1929).

These films demystified the prevalent notion of the samurai as honorable heroes and depicted them as ordinary human beings who barely manage to survive in a cold, cruel world. Even though Makino emerged as a socially conscious filmmaker, it is true that most of his postwar films are fairly routine.

After World War II, he soon found himself working for the aspiring Toei Company where the now highly regarded veteran was busy directing the usual company product: countless trivial period films in the 1950s and ninkyo eiga-type yakuza films in the 1960s.

Yet, as the film critic Sadao Yamane argues, the director’s rushed filming practice “also contributed to Makino’s speedy, rythmic film style.” Though the stories are prosaic, most of Makino’s postwar films have gained other features from his unquestionable expertise.

For instance, the lyrical poetry of The Red Cherry Blosson Family (Junko intai kinen eiga: Kantô hizakura ikka, 1972), the retirement film of great Yakuza film icon Junko Fuji; the genuinely funny period comedy, Bull’s Eye of Love (Oshidori kago, 1959); or the highly atmospheric, yet somewhat dull Tateshi Danpei (1950), written by none other than Akira Kurosawa.

Makino’s Western equivalents might be directors like Michael Curtis or Anthony Mann, who seldom left familiar genre patterns, but whose expert craftsmanship made even their minor works never less than entertaining.

8. Kazuo Kuroki (1930 – 2006)

The son of Masahiro Makino, Kazuo Kuroki’s work as a filmmaker couldn’t be further away from the mostly conventional studio programmers in which his father specialized. Directing his first feature film in 1966—when the Western interest in Japan’s artistically daring and innovative art films had waned—Kazuo Kuroki’s imaginative and experimental works were mostly ignored by Western critics.

In Japan, however, he already established himself as one of the most fascinating new filmmakers with his first film, Silence Has No Wings (Tobenei chinmoku, 1966). Connected by the image of a caterpillar being unintentionally transported from Nagasaki to Hokkaido, the film functions as an allegory on the Japanese post war society told through several human stories.

Kuroki’s creative use of a handheld camera and his poetic nature imagery earns his spot on this list. One of the first scenes alone, showing a boy hunting a butterfly, must be named one of the most visually lyrical and moving sequences in the history of Japanese cinema.

In the following years, Kuroki continued to cultivate a lyrical and poetic film style while observing the Japanese postwar society. The films Tomorrow (Ashita, 1988) and Face of Jizo (Chichi to kuraseba, 2004), for example, deal with the aftermath of the atomic bomb; other films are deeply rooted in genre cinema but transcend genre mechanisms with visual experimentation and philosophical themes.

Thus, the yakuza film, Evil Spirits of Japan (Nihon no akuryo, 1970)—despite culminating in a rather atypical one-against-all climax—primarily is an existential drama about a cop and a criminal changing identities.

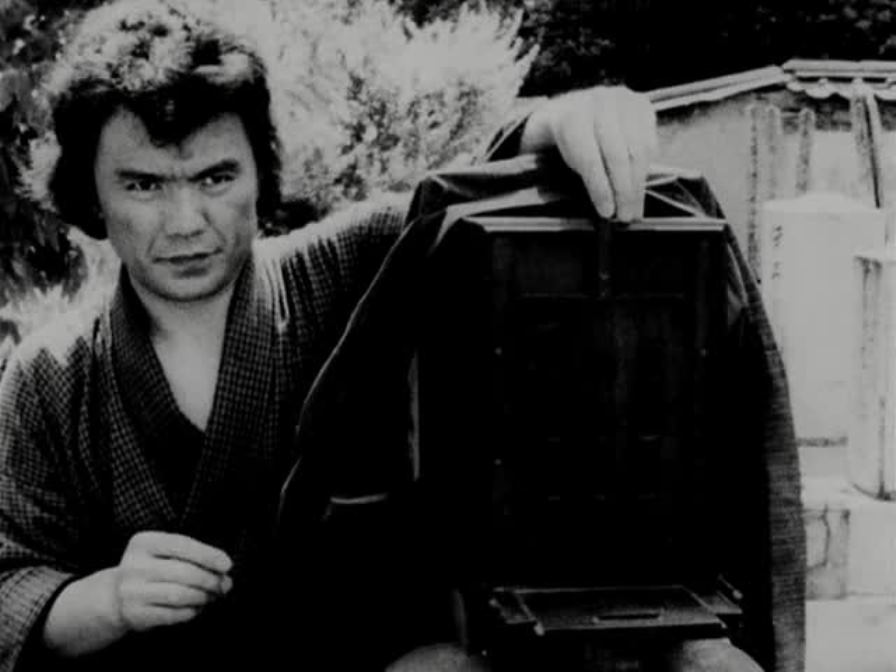

Yet, his masterpiece is probably the independently produced jidai-geki, The Assassination of Ryoma (Ryoma ansatsu, 1974). Shot in grainy 35 mm, and mimicking old black and white photos, the film portrays the historical figure Ryoma Sakamoto (1836-1867), whose progressive ideas were integral in overthrowing the Tokugawa shogunat, which led Japan to modernity.

Both melancholic and funny, the film denies Sakamoto any idealization; instead, he is perceived as an ordinary human being. Nontheless, Kuroki, pays tribute to Sakamoto`s revolutionary ideas.

In Roningai (1990), Kuroki paid homage to his father by remaking one of the latter’s greatest successes. Though it is well-crafted, the film is quite pedestrian and not one of Kuroki’s best works. Nevertheless, it gave seasoned genre star, Shintaro Katsu, a memorable last screen credit.

Katsu’s character, the dilapidated Ronin, proved that Kuroki transcended above everything he touched. The filmmaker’s use of characterization is mastery, especially with his poetic film style and his fine sensibilities in drawing his actors’ screen personas.

7. Tai Kato (1916 – 1985)

Among the many almost unknown directors featured in this list, Tai Kato is probably one of the least known in the West; even in Japan, he seems to be largely forgotten. Yet, the critics’ negligence of his filmography should not mask fact that Tai Kato could actually be named one of the most influential filmmakers of Japanese cinema.

The nephew of renowned director, Sadao Yamanaka, Kato initially started by directing documentaries during the war. He made his first feature film for the production company, Takara Productions, where he subsequently churned out several low-budget jidai-geki. In the late 1950s, he switched over to the aspiring Toei Company, where he was assigned to shoot so-called Toei gorakuhen (Toei Entertainment Edition).

Usually those films were trivial jidai-geki—with young stars, covered in heavy make-up—which were designed to play at the lower end of a double-feature. Instead of repeating the usual stereotypes prevalent in those type of genre films, Tai Kato managed to infuse this genre with a groundbreaking sense for realism.

In films like Wind, Woman and Vagabonds (Kaze to onna to tabigarasu, 1958) or Ghost of Oiwa (Kaidan Oiwa no borei, 1961), he abolished the use of make-up entirely, providing credibility to the screen characters by carefully drawing on the respective actors’ personalities.

Some critics argue that director Akira Kurosawa—with his gritty realism and unheroic action scenes—revolutionized the jidai-geki. Kurosawa, however, directed big-budget films, and his sheer magnitude was unreachable for the average contract director. Tai Kato, on the other hand, directed low-budget features.

Thus, it is an understatement to claim that he was an even more pivotal figure than Kurosawa, especially in the transformation of the period film—from simple escapist entertainment in the ’50 to the more the serious, nuanced and violent jidai-geki of the ’60s.

When the Toei Company started producing ninkyo eiga in the ’60s, Kato enhanced these genre films with well-drawn characters and a somber atmosphere, which often resulted in uniformly great performances by his actors. Junko Fuji, one the greatest stars of the ninkyo eiga, called Kato’s film Blood of Revenge (Meiji kyokaku: Sandaime shumei, 1965) her personal favorite of Toei Company’s ninkyo eiga.

The rushed mass production methods of his company also taught Tai Kato to cultivate his unique and highly economical style. His camera often remained in fixed, low-angle positions, running an unusually long time, so as not to interrupt the natural, emotional flow of his films.

Beginning in the 1970s, Tai Kato—who always tried to refine his style from film to film— experienced a period of unrestricted excellence. Among the many masterpieces, often long and complex yakuza or jidai-geki epics, he made in the last years of his career, especially his last work, Like a Burning Flame (Honoo no gotoku, 1981) deserves wider exposure.

The moving story of a Bakumatsu era gambler, whose tragic quest to protect the beloved women of his life often ends in misery, ranks among the last really great jidai-geki. The film signified Tai Kato’s importance as a director, who transcended stereotyped narratives of genre films. His skills make his films truly unique and often masterfully crafted classics of the Japanese cinema.

6. Kosaku Yamashita (1930 – 1998)

Like Tai Kato, Kosaku Yamashita worked as a contract director for Toei. While his films seldom reached the heights of Kato’s best works, Yamashita was nevertheless a director of taste and integrity. He never let the generic nature of his many genre pictures limit his talent for the creation of atmosphere and for milking sincere pathos out of often hackneyed scenarios.

Yamashita made his debut in 1961, but he first gained acclaim for his third feature, the matatabi eiga: Yakuza of Seki (Seki no Yatappe, 1963). The film is an adaptation of a well-known novel about a feudal yakuza who cares for a fatherless child—one whose father was killed before his own eyes.

Yamashita, however, transcends the story into a genuinely moving tragedy of a low-born man being forced to take the violent path of a wandering gambler—instead of a common citizen—due to the demands of his criminal environment.

However, Yamashita didn’t come fully into his own until the 1960s when Toei switched from producing jidai-geki to yakuza eiga. In those days, Toei’s gangster film output consisted mainly of so-called ninkyo eiga, films. Primarily, honorable yakuza were caught in a steady conflict between their often cruel obligations toward their yakuza brothers (giri) and their human emotions (ninjo).

Often those films were reactionary and generic; In Yamashita’s hands, however, the genre flourished. His film, Big Gambling Ceremony (Bakuchiuchi: Socho tobaku, 1968), is hailed by genre aficionados as one of the greatest classics of the Japanese gangster film.

The story is about a noble yakuza who fulfills his duty toward his boss by bringing misery upon himself, and Yamashita brings the central giri-ninjo conflict to its very essence. In fact, the last statement of the main character—played by ninkyo eiga icone Koji Tsuruta (before he finally slays his devilish boss)—belongs to the most celebrated lines of the genre: “I know nothing about the way of the yakuza.”

Yamashita also directed Red Peony Gambler (Hibotan bakuto, 1968). First of a revolutionary film series, the director transformed the male-oriented genre by casting a female yakuza in the lead role.

By giving the female lead a strong—but feminine and sensitive—personality, Yamashita and script writer, Norifumi Suzuki, created a completely new type of action heroine—one who simultaneously enchants and slices up her enemies. Actress Junko Fuji turned into a successful film star into after performing in this film of tremendous proportions.

Yamashita remained a stalwart of Toei’s until his death in 1998, directing everything from big-budget war movies to the more realistic jitsuroku eiga-type yakuza eiga. Yet, his greatest works were made within the ninkyo eiga circle.

Unparalleled by gangster films from other countries, Yamashita’s unobtrusive mise-en-scène, sincere pathos, and strong emphasis on the giri-ninjo tragedy—which often tore apart the characters of Yamashita’s films—gave those works a bleak and dense tone. By creating them, Kosaku Yamashita repeatedly proved himself again as the great master of the ninkyo eiga.