8. Before Sunset (2004), dir. Richard Linklater

Richard Linklater’s second movie on this list is the second installment of his Before Trilogy. This film was directed nine years after Before Sunrise (1995), where a young American man Jesse (Ethan Hawke) and a young French woman Celine (July Delpy) meet on a train and spend one night in Vienna.

In Before Sunset, the two lovers meet again, by chance, and of course in Paris. Jesse has a little bit more than an hour to catch a plane, but when he sees Celine, they wander around the Paris streets together. The love that shapes their brief, first encounter in Before Sunrise illuminates in this film.

The audience follows the lovers as they discuss life, love, and marriage; they are observed by viewers in real time so there is not any dialogue disconnection. Since the concept of love is integral in this film, any single word—spoken or not—is important. Linklater applies the real time technique here not only to intensify each moment, but also to capture the essence of true love.

7. Dog Day Afternoon (1975), dir. Sidney Lumet

Dog Day Afternoon is another movie on this list that is directed by Sidney Lumet; It is apparent that the director was really fond of the real time technique. This masterpiece remains memorable for its great performances by Al Pacino, John Cazale, Charles Durning, Chris Sarandon, Penelope Allen, James Broderick, Lance Henriksen, and Carol Kane. Truthfully, though, the real time technique perpetuates Dog Day Afternoon’s battle with time.

Inspired by Thomas Moore and P.F. Kluge’s article, “The Boys in the Bank,” Dog Day Afternoon is the story of first-time crook Sonny Wortzik (Al Pacino), his friend Salvatore “Sal” Naturale (John Cazale), and Stevie (Gary Springer) who attempt to rob the First Brooklyn Savings Bank. The real time technique reveals the documentary style of the film, which helps the audience picture the tension and issues from which the U.S. was suffering in the 1970s.

6. My Dinner with Andre (1981), dir. Louis Malle

In New York during the late 1970s, two men in a café discuss life, existence, and theater. Though this scenario isn’t anything new, and the film isn’t that interesting, Louis Malle’s 1981 movie is both funny and thought provoking.

The crafty dialogue of its two main characters, Andre Gregory (as himself) and Wallace Shawn (as himself), and its real time technique represents the similarities between cinema and theatre. The logical connection between real time and a compelling narrative is partially because Gregory is a former theatre actor; thus, it is simple for audience to witness a simple, yet deep, story of two men conversing behind a dinner table.

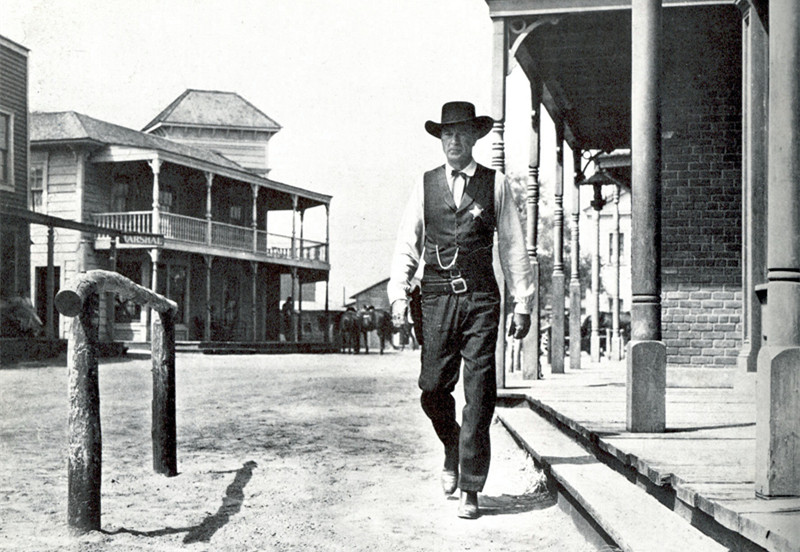

5. High Noon (1952), dir. Fred Zinnemann

High Noon is indubitably one the best Western movies of all the time. Directed skillfully by Fred Zinnemann, it tells the tale of Will Kane (Gary Cooper)—the longtime marshal of Hadleyville, New Mexico Territory—who turns in his badge, marries pacifist Quaker Amy Fowler (Grace Kelly), and intends to become a storekeeper elsewhere. Suddenly, the town learns that Frank Miller (Ian MacDonald), a criminal whom Kane brought to justice, is due to arrive on the noon train.

It is almost impossible to imagine that High Noon could be made any other way than in real time. The arrival of the enemies is certain, and Will Kane has only about two hours to decide about his future and who his true friends are. The viewer will never forget the ending duel. One will constantly look at his or her watch to see how fast time has gone, though it seems in such a short amount of time, there is much more to be accomplished!

4. Russian Ark (2002), dir. Alexander Sokurov

Russian Ark is an experiment of a life time. The movie—filmed in one continuous shot, with a camera that moves leisurely around St. Petersburg’s Hermitage Museum—contains more than 2000 actors and narrates the 300-year history of St. Petersburg in 96 minutes. The film breaks the mold when the “dead” narrator talks to the audience. Last, but not the least, the movie occurs in real time, as if the viewer is a visitor of the museum, moving along its corridor and familiarizing oneself with the city’s history.

The experimental stake of Russian Ark is so high one can’t ignore it. Thus, unsurprisingly, the film was an international sensation and participated in many film festivals, including Cannes.

Moreover, the director’s use of real time here is not just to place the viewer inside of a museum. In fact, the film also contains a philosophic function: history is continuous. Thus, if the audience is supposed to learn a historical lesson, perhaps it is to view history without any gaps.

3. 12 Angry Men (1957), dir. Sidney Lumet

It appears that fate and the real time technique are inseparable. In Sidney Lumet’s masterpiece, twelve jury members must deliberate the guilt or acquittal of a defendant on the basis of reasonable doubt. The movie has been always hailed for its actors’ great performances, most notably Henry Fonda and Lee J. Cobb. It was deservedly nominated for Academy Awards in the categories of Best Director, Best Picture, and Best Writing of Adapted Screenplay.

However, one may or may not realize that the film takes place and is narrated in real time; how, then, is the director’s use of this technique important? Watching the movie, the audience feels they are in the shoes of the jury members. The film forces the viewers to become voyeurs, as they sense the tension of deciding one’s fate and life. Thus, 12 Angry Men is more effective than other types of courtroom dramas because of its narration in real time.

2. Rope (1948), dir. Alfred Hitchcock

One of Alfred Hitchcock’s most innovative movies, Rope takes place in real time, and of course, the movie consists of only ten long takes. The movie is about two brilliant, young aestheticians—Brandon Shaw (Dall) and Phillip Morgan (Granger)—who, in their own apartment, strangle a former classmate, David Kentley (Dick Hogan). They commit the crime as an intellectual exercise; they want to prove their superiority by committing the “perfect murder.”

After six decades, Rope is still a fresh film, and one may enjoy the way Hitchcock has eliminated editing by his mise-en-scène. However, it is the real time technique he uses that adds thrill and suspense to the film.

1. Cléo de 5 à 7 (1962), dir. Agnès Varda

Agnès Varda’s innovative and wayward movie narrates the story of a girl (singer Cleo) waiting for the results of a medical test. Varda playfully presents two hours of Cleo’s life, and like any other French New Wave film, Cléo de 5 à 7 (Cleo from 5 to 7) is full of long dialogues about life, death, hope, and despair. Varda emphasizes the film’s natural real time by dividing it into several chapters that last a few minutes each.

In approximately two hours, the audience experiences how general life in contemporary (60s) France is “black and white,” and an individual’s existence depends on the way he or she perceives it. Varda distinctly depicts this concept in the short film (starring Jean-Luc Godard and Anna Karina) that Cleo watches in a cinema. The movie is an intimate portrayal of a woman’s life, and the real time technique repeatedly reminds the audience of her hopes and worries.

Author Bio: Hossein Eidizadeh is a film critic and cinephile from Iran. He has interviewed David Lynch, Margareta von Trotta, Barbara Sukowa and many others. He writes film posts on his blog closeupkino.blogspot.com.