7. Eyes Without A Face (1960)

Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face was almost defanged by censors across the Western world, and it still found itself the main event at a critical slaughter in France upon its 1960 release. It’s easy to see why; the film’s plot, about a scientist (Pierre Brasseur) stricken by grief over the destruction of his daughter’s face and driven to murder for skin to replace it, more closely approximates a lurid B-movie than anything else. But the plot’s greatest effect was to convince Franju he couldn’t but make the movie with the utmost seriousness and highest artistry. That he did, and the end result is a horror film unlike any other.

The undeniable highlight of the film, however, is Edith Scob as the young woman eternally mocked by the mask she’s forced to wear to cover her dismemberment. Whatever color the mask was in person, the profoundly fleshy grey of the celluloid only sees it as human. The effect is to show Scob wearing a formless mask lacking any sense of humanity that nonetheless defines itself as inseparable from her face, same skin tone and all.

It is impossibly sad and eerie, especially when she requires it to move later on, to speak as she does, and it apes the human form but with no sense of expression whatsoever. If the mask is clinical, it depicts Scob herself as a person lost in her own emotion, eternally sad to the point of perpetual mourning. The film exploits Scob’s beauty, and her wonderfully solemn, expressive eyes, to create something truly disconcerting; an image at once monstrous and angelic.

Outside of Scob, the film’s tone is impossibly mournful and longing, creating a Shakespearean tragedy that would be melodramatic if it weren’t so plaintive. Visually, Franju’s work airs on the restrained side, but his framing does wonders with depicting and not depicting the film’s titular objects. It also pairs extraordinarily well with the film’s mesmerizing score, equal parts tragic, jaunty, and horrific. In particular, the opening theme is worried in a decidedly joyful way, like a nightmare carnival taking total and complete control of us and letting us know it’s enjoying every bit of it.

6. The Haunting (1963)

Director Robert Wise remains far more famous for his work in the musical genre, but his roots are all horror, right down to his first job directing for none other than Val Lewton himself. His greatest film, in any genre, remains one of his final horrors, The Haunting, a work which maintains the theatrical, grandiose technique found in his much lighter films but marries it to heaving visual chaos and soul-struck chills.

Not only does it use its grandiosity to give us the greatest haunted house in all of cinema – expressionist angles creating a heaving mass of drearily opulent geography sucked of emotion – it bleeds the house in reality and the house in the mind. In doing so, it calls into question the existence of “space” as we know it, and it has a darn giddy time messing with us while it’s at it.

Wise’s film is also deeply voyeuristic, feeding us its own intentionally confused identity by the spoonful. It questions our sanity, and its own storytelling perspective, at every turn. Mostly, this comes from Wise’s camera, itself a participant in the narrative even as it never gives us the voice of any one character in the film. Instead, it films from a space so close to its characters – but not quite one with them – that it can neither truly be subjective or objective. It’s stuck in the limbo in between, always there, observing the characters, watching, writing down notes, and ready to pass judgment.

This camera, more than any of the film’s narrative characters, suffers from a tortured identity. It is ever-unsure of whether to sit still in a shocked fright or to tremble about with angry humanity. When it is married to Wise’s stunningly concrete and expressionist use of sound, alternating between inhuman wails, gasped silence, and lurid stand-ins for everyday noises, it creates a film where form and content are wholly in unison.

The camera also comes anxiously close to breaking the fourth wall, at one point hitting the ground and shaking as if a human would. Yet this is a sign of something more broadly at stake in the film: when a character quite literally comments on how the whole house is a product constructed for fear, Wise is peeling back the layers of the horror film as an entity. In this regard, the film’s own haunted house is a metaphor for the playground fear-making of film itself.

5. Bride of Frankenstein (1935)

James Whale’s 1935 sequel to his first masterclass in horror, 1931’s Frankenstein, is the impossible: even better, and for few of the same reasons. The most iconic things, Boris Karloff in his most famous role and the monster’s famed ghoulish design, return, but the tone is radically different. While that film was rather straight, albeit masterful, horror, this one is equal parts theater piece, gallows comedy, kitsch-fest, and campfire story-time. It’s an all-together strange film, one of the most radical sequels ever released, and it is all the more gloriously alive for this very fact.

The film announces its loopy intentions right from the beginning, with a post-structuralist opening scene that has fun with the visual logic of horror. We open on a classic sight: a spooky castle with stormy weather all-but threatening to swallow it up for good. We expect Dr. Frankenstein and all manner of pseudo-science lighting up the darkness like fluorescent madness, but we’re treated instead to something even zanier inside: Mary Shelley explaining the contents of her book, which she then regales us with.

The film, in opening up on a bit that explicitly tears down the then-popular logic of continuity storytelling, informs us at once that this is not the Frankenstein we were expecting, and that, more than anything, we are about to be treated to a proper tall tale, a lark. To this extent, the film is at our service. It sets a gloriously left-field field ball rolling that doesn’t stop for anything.

After this sequence, the film tiptoes a line so razor-thin between horror, tragedy, and gallows humor, it soars sky-high on the sheer tension it creates through threatening to implode on itself. Firstly, the film is rather in the monster’s corner this time out, with Karloff ing him as a child let loose on the world struggling to comprehend its contradictions and inadequacies. More than horror, the film evokes mirthful joy and childlike glee, as well as soul-deep trauma, when we witness the monster love and lose within the span of minutes. It takes us to the pit of guilt and the summit of innocence, often within the same scene.

As if that weren’t already enough, the B-plot, about Dr. Frankenstein and a fellow doctor attempting to create life for Frankenstein in the form of a Bride, is off somewhere simmering with campy psycho-sexual tension that fascinates with its perturbed energy.

The film is so busy poking and prodding at society and humankind and filmic invention it occasionally forgets to frighten – but when it does, any concern is washed away. Bride of Frankenstein is horror at its most frustrated, excited, and delirious, a film that takes a sort of pure, sheer joy in screwing with us, refuses to be classified, and always comes back for more. More than anything, it is the very antithesis of sequel logic, and it is endlessly fascinating.

4. Ugetsu (1953)

It’s a shame Mizoguchi’s name has been almost wiped clean from the canon, but it’s easy to understand considering his total and complete distance from anything resembling modern film-making. If Kurosawa was a story-teller and Ozu a painter – two things very much still alive in today’s film-world – Kenji Mizoguchi was a fable-maker. A director who bled physical space but abstracted it to find the unconscious spaces of our mind layered within, Ozu’s greatest tool was the elegiac long take. He had no interest in cutting to capture characters as individuals, and found himself far more compelled by the idea of people in relation to their environments.

Naturally, an emphasis on geography lends itself to horror, but the genre was not Mizoguhi’s forte. He usually worked with a particularly horrifying, malaised, haunting form of drama – look no further than Sansho the Bailiff, arguably his greatest film. But Ugetsu is dramatic horror, subsuming narrative to mood, using atmosphere to define character, and elevating imagery to a sort of hazy, heavenly film-making that feels leisurely yet undeniably poetic.

Ultimately, Mizoguchi cares very little about plot and very much about feeling. He lets his films breathe, giving them an air wholly at odds with the norms of the horror genre. His cavernously wide shots capture a profound emptiness, of miniscule people crushed under the weight of their own insignificance.

It wafts around, fills the cracks of our minds, and gives us a space to sit around in and explore. Of course, it doesn’t leave us unguided – it gently prods us toward the darker corners of the human mind, and forces us to confront them with nothing left between us and our barest emotions. The end effect is cinema’s greatest unholy dream, as eerie as it is darkly seductive.

3. The Night of the Hunter (1955)

Charles Laughton’s only directorial effort destroyed any future chance of a career behind the camera. Perhaps the film was too anxious, too radical, or just too stunningly left-field and out-of-touch with anything considered “good” film-making as of 1955. Or maybe it was just too terrifying.

As American film-making has only gone further embraced continuity editing since then (with few exceptions, namely the entirety of the 1970’s), it is no less radical, and no less magisterial today. With each shot, we hear the death rattle of a career still in the womb; but as for what we see, that is most certainly a different story.

The Night of the Hunter is most famous today for Robert Mitchum’s glorious huckster, a criminal masquerading as a preacher and on the hunt for two children who know where their father has hidden a surfeit of money he stole. The performance is monumental, to be sure, equally depraved and avuncular, a sooth-sayer for the ages. But the pall it casts over the film tends to distract from how subversively and maddeningly well constructed it is, with impressionist sound design basking in the moonlight and some of the finest shadow use ever featured in an American film.

The childrens’ river boat trip, its most famous scene, is as magical as it is disturbing, and melds German expressionism with a more French form of impressionism. But other scenes, such as one where the preacher Powell murders the childrens’ mother, laying on a bed and encased in a coffin of light, wring raw beauty out of grueling tension.

The most radical thing about the film, perhaps the one which turned people off the most, is that it doesn’t subscribe to any one particular cinematic language. In addition to impressionism and expressionism, there’s a harsh realism to the film, no doubt the impression of writer James Agee’s life and the loss of his father at a young age (mirrored here). Yet the film is also an openly religious parable about good and evil, and everything is subsumed with an undeniable air of the Southern Gothic.

It’s an indefinable film, but as a horror that plunges into the depths of the human experience and melds the dreamy and the nightmarish to come out on the other side forcefully composing itself to hide the aching, self-destroying emotions under-neath, it’s the cinema’s ultimate fable of human existence.

2. Psycho (1960)

Few films have been prodded at, analyzed, observed, examined, steamed, pressed, and burnt to a crisp like Alfred Hitchcock’s first foray into true horror. Indeed, in some respects, it may be the most important film made since its release, or at least the one that has most shaped the ensuing 55 years of film. That it is also a stunner in its own right sometimes plays like an afterthought, but it’s important to remember nonetheless.

And any analysis of Psycho begins with Hitch’s mind-bending narrative self-destruction. Pscyho follows one very clear narrative down the rabbit hole for half of its running length and then blows up the hole. It performs one of the most graceful, yet intentionally jarring, fundamental story self-mutilations in filmic history, and it does so wrapped in a barbed-wire commentary on the nature of performance and the movie star.

After all, with Janet Leigh in the film, it is assumed – even regardless of her clearly less than likable character – that any audience will ultimately want to follow her, and on this front, Hitch lulls us into submission and then smashes our hopes forthrightly. He clearly enjoys it too.

The second half of the film also happens to be a truly stunning work in itself, filtered through an arch-clinical detachment we never see in this sort of genre and capturing something far scarier than the normal filmic sensation of “being” a killer. It captures something less common – the feeling of sitting next to a murderer or killer, knowing it, and knowing that they do not yet know, and being absolutely helpless to do anything about it as Hitch intentionally holds us back at a distance.

Although Hitch’s direction stands out in a few particular scenes – the noted shower sequence which may be the most perfectly edited minute of film ever, and the famously disorienting, intentionally sloppy, tumble down the stairs – the whole film is a masterclass in escalating tension and subversive direction. In other words, not only did Hitch take on a genre – he just about perfected it.

1. Vampyr (1932)

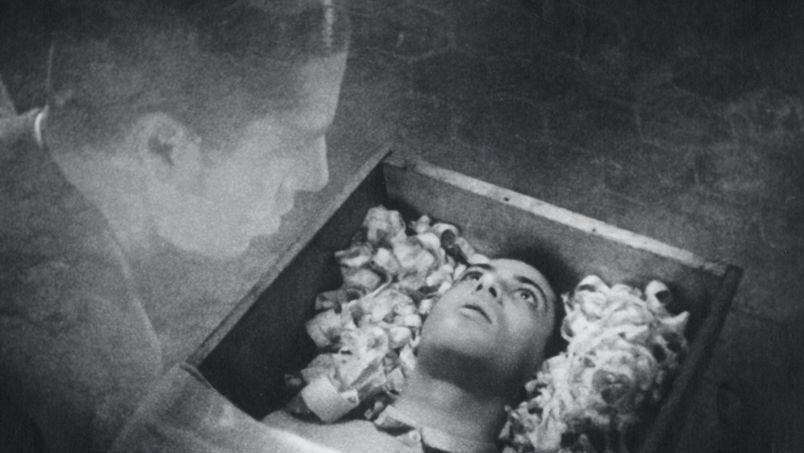

Deep in the heart of the post-German-Expressionism American horror craze (largely populated by Universal’s slate), no film challenged the idea that only hard angles and grain-stricken blacks can be chilling beyond belief like Carl Theodor Dreyer’s 1932 tone-poem of hazy malaise, Vampyr. It’s heavily indebted to German expressionism, yes. But it replaces angularity and high-contrast black-and-white with a barely-there haze and sense of passing presence that threatens to suck the very meaning of black and white from the terms. There was nothing like it at the time, nor is there today, in cinema, or in life.

The film’s plot can’t be tied to event – it is a story of our relationship to the images and sounds on screen, and nothing more. Essentially, there is a man who explores a town and observes things that ought not be there, and this allows Dreyer to coax us into viewing these things.

The film works, simply put, because of what we are viewing, and how tenuously and tentatively its images shall continue to exist. It blends styles like they’re cereal – it marries aspects of expressionism to a deeply impressionist mise-en-scene, both of which are thrown for a loop due to Dreyer’s famed dramatic use of piercing close-ups that threaten to scratch the celluloid itself.

If Vampyr knows no approximate, it’s because it doesn’t approach us as something of the human world. It’s less a finished film than an afterimage of a work from another world, a sliding dream we move in and out of that knows nothing of pesky everyday concerns like cohesive narrative. It’s a purely visual piece, but it may do more with visuals than any other film in existence.

If there is one glue holding the film together, it is that Dreyer intentionally shot every image through a layer of gauze, hoping to give the film an indefinable transparency. It works, capturing not so much a work made by a film-maker as an aura felt and forgotten long ago, struggling to remember itself fully but still deeply latched onto the unconscious of the mind. It’s a deeply sickly film, constantly threatening to fade away on a moment’s notice. Perhaps for this reason, we should take every minute to cherish it.

Author Bio: Jake Walters is a recent graduate of Amherst College and an aspiring film-writer/ist. He shares his thoughts on film at his website, thelongtake.net and is particularly interested in film in relation to society, race, class, and gender, He writes frequently on horror films and looks to Werner Herzog, Michel Foucault, and John Shaft for life advice. You can find him on Twitter@long_take.