8. Kwaidan – 1964, Masaki Kobayashi, Japan

Kobayashi’s Kwaidan transformed the portmanteau subgenre of horror films popularised in the 60s and 70s by the Amicus and Hammer studios into a genuine work of art. Divided into four chapters, the film is based on four stories from Lafcadio Hearn’s collections of Japanese folktales, primarily Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things.

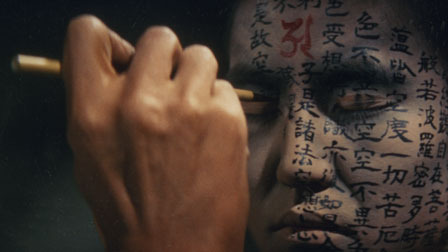

All four sections are excellent, but the best is undoubtedly ‘Hoichi the Earless’ – the tale of a blind musician of unsurpassed skill commanded by a ghostly imperial court to perform the epic ballad of their death battle. Drawing on aspects of Kabuki and Bunraku puppet theatre, Kobayashi makes few concessions to realism, instead drawing out the very theatricality of his source material to create one of the finest depictions of the supernatural ever to appear on screen.

Filmed completely in studio (a converted aircraft hangar was actually required to satisfy the scale of Kobayashi’s ambition) with sumptuously painted backdrops, Kwaidan makes a virtue of its own artificiality throughout; Kobayashi’s extraordinary use of light, expressionistic colour, and astonishing compositions drawing on his training as a student of painting and fine arts.

Equally remarkable is the soundtrack by Tōru Takemitsu: all strange clinks and clangs, unearthly vocal chants, plucked biwa strings and whispering shakuhachi flutes, interspersed with John Cage-inspired silences, it’s as eerie and disconcerting as the film’s magnificently haunting visuals.

Winner of the Special Jury Prize at Cannes, Kobayashi’s supernatural tour de force is a truly transportive experience – the cinematic equivalent of a portal into the supernatural world itself.

7. Orphée – 1950, Jean Cocteau, France

In the second part of Cocteau’s Orphic Trilogy, the French polymath artist gave his take on the Orpheus and Eurydice legend, reconfiguring the Thracian lyre-player as a famous Left Bank poet in post-occupation Paris.

Adapted from Cocteau’s own play, the film portrays the growing obsession of Orphée (played by Cocteau regular Jean Marais) with a mysterious black-clad princess whose leather-uniformed, death-dealing motorcyclists first claim the life of a rival poet, and then Eurydice, his wife. A reminder that the Surrealists wandered into their world of dreams hand in hand with Freud, Cocteau presents an Orpheus driven as much by Thanatos as by its opposing drive of Eros.

Considered by many to be Cocteau’s finest filmic achievement, even at a distance of over 60 years its special effects (particularly the dissolving mirror through which the characters pass into the underworld) still beguile. But it’s the overall dreamlike feel of the picture and its vision of a death-haunted universe that stays with you.

6. Häxan – 1922, Benjamin Christensen, Sweden/Denmark

Although witchcraft (as a practice) is not a myth per se, Benjamin Christensen’s remarkable documentary-cum-horror silent film Häxan is worthy of inclusion for the way it brings to life the superstitions and folklore which surrounded and informed the witch-hunt craze that spread devastatingly throughout much of Europe during the 14th to 17th centuries.

Ostensibly Häxan is a serious documentary contrasting the misinformed superstitions of the Middle Ages with the (now equally questionable) treatment of female hysteria in Christensen’s own day, but there’s also a great deal of black comedy at play. Revealing a mischievous sense of humour, Christensen casts himself as both Satan and Jesus Christ, while the film’s gallery of dissolute friars, sexually frustrated monks and gullible peasants all act as grist to the director’s satirical mill.

Conversely, in being based on actual historical events, the film attains a level of terror no conventional horror piece could ever achieve. The influence of Murnau and German Expressionism can be detected in places, but Häxan’s unholy mixture of nudity, violence, extraordinary animated sequences and cast of grotesquely made-up demons is quite unlike anything made before or since.

An alternate shortened version was released in 1968 entitled Witchcraft through the Ages, with a William S. Burroughs narration and a crazy jazz soundtrack adding another layer of weirdness to what was already a very mad film.

5. Alexander the Great – 1980, Theo Angelopoulos, Greece

Theo Angelopoulos’ 1995 film Ulysses’ Gaze may have taken inspiration from Homer’s Odyssey, but the Greek director’s attitude towards his nation’s rich mythological heritage was always an ambivalent one – once describing classical Greek antiquity as a millstone the Greek people are forced to bear. Although inspired by a legend from Greece’s medieval period rather than its antiquity, a similar ambivalence underscores Angelopoulos’ treatise on myth, history and revolutionary politics, Alexander the Great.

The film’s plot is loosely based on the Dilesi Incident of 1870, when the abduction and murder of a group of British aristocrats and an Italian count by Greek brigands at Marathon led to a British blockade of Greece and significant tension between the two nations. In the film, the bandits are led by an enigmatic character dressed in the armour of a Greek medieval warrior, the eponymous Megalexandros.

Confusingly translated into English from its original O Megalexandros, the film’s title and main character do not refer to the historical Macedonian ruler, but another Megalexandros – a legendary Greek liberator and King Arthur-esque figure whose tale originated in the 15th century when Greece was under Turkish domination. When Angelopoulos’ messiah-manqué seeks refuge in a mountainside village commune built upon socialist values, the villagers soon fall under his increasingly totalitarian rule.

With its glacial pacing, 192 minute running time and complex allusions to a specifically Greek cultural, socio-political and historical milieu, Alexander the Great is a demanding watch, but an undisputed masterpiece of Greek cinema.

4. Funeral Parade of Roses – 1969, Toshio Matsumoto, Japan

The flipside of Pasolini’s comparatively ‘straight’ telling of the Oedipus myth, Matsumoto’s Funeral Parade of Roses places the drama within the gay subculture of 1960s Tokyo to tell the story of Eddy, a popular young transvestite who murders his own mother before embarking on an affair with a cabaret bar manager in the city’s gay district. No prizes for guessing the identity of Eddy’s estranged father.

In many ways, Funeral Parade of Roses is very much a product of its counterculture time, with its restless experimentalism, genre hopping, self-referentiality and Pop Art sensibilities owing an obvious debt to Godard and the Nouvelle Vague. But in recontextualising the central theme of identity from Sophocles’ play to examine non-heterosexual identities and sexualities, the film stands alone even within the highly experimental Nuberu Bagu (Japanese New Wave) scene.

Moving from sensual love scenes to explosive outbursts of violence, low comedy to high tragedy, while incorporating documentary-style realism with wild, highly-stylised fantasy sequences, Funeral Parade of Roses makes for essential cult cinema viewing.

3. Medea – 1969, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Italy

Pasolini concluded his ‘Mythical Cycle’ with possibly the greatest rendering of Greek myth in all of cinema. The film takes us to the world of Colchis, where Jason has travelled with his Argonauts to claim the magical Golden Fleece that will restore to him the kingdom of Iolcus usurped by his uncle. Colchis is presented as an agrarian community, but one also in thrall to other older, more primitive ways.

We see the sacrifice of a young man; his body hacked into pieces, the blood and dismembered parts spread through the land to cultivate the crops. It is in essence the birth of tragedy (the dramatic form with its roots in the figure of the sacrificial scapegoat amid Dionysian rites), which would reach its apogee in 5th century BC Athens and whose Euripidean Medea informs Pasolini’s film.

But we are also given the beginning of the end for the mythic world. When Jason arrives in Medea’s homeland it marks a collision of two worlds: Jason’s one of proto-scientific, rationalism against Medea’s one of superstition and magic; a collision which will be to the detriment of the latter world.

Transported from Colchis, the Fleece becomes no more than a damp rag, and Medea – a sorceress and the granddaughter of a god – finds her powers diminished when she abandons her homeland for the fickle, self-centred Jason. As terrible as the old ways may appear, Pasolini makes us feel their loss and what that loss may mean to our own apparently enlightened times.

This is the moral of the lesson given by Jason’s centaur-teacher in the film’s opening: ‘That which man, discovering agriculture, saw in grain, that which he understood from the example of seeds that lose their form beneath the earth to be born again, all that has become the ultimate truth: resurrection. But the ultimate truth is no longer valid. What you see in the grain, in the growth of the seed has lost all meaning for you. Like a discarded memory. In fact, there is no god.’ Later, as part of that process of desecration, the centaur will be revealed as just a man.

Maria Callas, in her only film role, gives a controlled but charismatic performance as the spurned queen; her performance perhaps drawing on personal experience (the opera singer had recently been unceremoniously dumped by the Greek shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis so he could marry Jackie Kennedy). But it is Pasolini’s rich evocation of the mythic Colchis that stays with you.

Filmed in and around the early Christian churches of Göreme and accompanied by a non-diegetic soundtrack of Iranian love songs and Japanese and Tibetan ritual music, the virtually dialogue-free scenes play out almost like an ethnographic documentary (albeit one featuring graphic scenes of human sacrifice and sparagmos). Pasolini’s violent poetic masterpiece elicits an atavism that is both repulsive and darkly alluring.

2. Profound Desires of the Gods – 1968, Shohei Imamura, Japan

Now acknowledged as a masterpiece of 60s Japanese cinema, Profound Desires of the Gods went largely unappreciated at the time of its release, while Imamura’s unhappy experience shooting his 18-month super-production led to him abandoning conventional filmmaking for almost a decade. After his return, he would go on to receive a deserved Palme d’Or for the similarly-themed 1983 film The Ballad of Narayama, but the earlier quite brilliant work remains Imamura’s magnum opus.

The film depicts the traditional society that exists on the fictional island of Kurage (a thinly veiled Okinawa), where the islanders are caught between their traditional shamanist religion and the promises of modernity when an engineer arrives from the mainland to supervise the drilling of a well.

Central to the story are the Futori, the oldest and most primitive family on the island, whose confused sexual relations mirror an indigenous creation myth in which the islands of Japan were created from discarded objects thrown by incestuous brother and sister deities. Nekichi and Uma Futori are the tragic sibling lovers at the centre of Imamura’s powerful allegory about Japan’s killing of its own traditional gods.

Combining Imamura’s customary anthropological interests with dazzling colour ‘Scope cinematography used to capture some of the most resplendent images seen in world cinema, the film (while not entirely representative of the movement) stands as one of the crowning achievements of the Japanese New Wave.

1. Nosferatu – 1922, F.W. Murnau, Germany

One of the earliest treatments of the vampire myth and perhaps the most iconic, Murnau’s silent horror was an adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, published only twenty-five years before. Unable to obtain the rights to the novel, Murnau simply changed names and other details (Count Dracula, for instance, became Count Orlok).

Stoker’s widow sued regardless; the resultant lawsuit forced the film’s production company into bankruptcy and all copies of the film were ordered to be destroyed. Fortunately, some prints survived of a film that would become a classic of the horror genre and arguably the most influential example of German Expressionism.

Of the changes made from the source novel by far the most significant was in the depiction of the vampire itself. As far removed from Stoker’s seductive, Romantic Dracula as can be imagined, Murnau’s Orlok (played by Max Schreck) is a truly unheimlich figure, closer in appearance and behaviour to the repulsive strigoi of Romanian mythology.

Although appearing on screen for less than nine minutes, his creepy, unsettling presence made such an impression that it led to rumours Schreck may not have been entirely human himself (an urban myth which would provide the basis for E. Elias Mehrige’s semi-serious 2000 horror film Shadow of the Vampire). Klaus Kinski would later reprise the role in Werner Herzog’s excellent 1979 remake Nosferatu the Vampyre, but Schrek’s original Count Orlok remains a singularly disturbing creation.

Author Bio: Gordon Knox is a writer and journalist from Edinburgh. He has a particular interest in Eastern European and Japanese cinema from the 1960s and 70s, as well as the films of Werner Herzog, Andrei Tarkovsky, Béla Tarr and František Vláčil.