20. Blood Simple (Dirs. Joel and Ethan Coen, 1984)

Julian Marty (Dan Hedaya) hires a PI named Loren Visser (M. Emmet Walsh) to investigate his wife Abby’s (Frances McDormand) infidelity. Little does Marty know that Visser has plans of his own to kill Marty and frame Abby. Blood Simple mixes dark humor and violence into a thrilling neo-noir.

The absurdist situations of the Coen Brother’s stories would become a trademark of their films, helping them to gains legions of devoted fans who relish in their brilliant films.

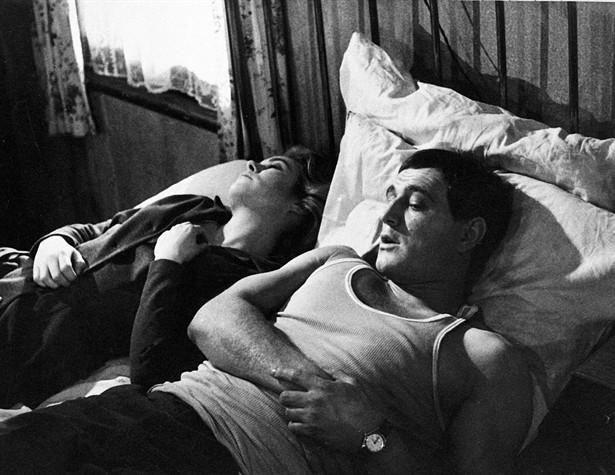

19. This Sporting Life (Dir. Lindsay Anderson, 1963)

Lindsay Anderson’s This Sporting Life follows Frank (Richard Harris), a rugby player who rises to fame and begins a relationship with his landlord, Margaret (Rachel Roberts).

Though British critics would openly criticize the film for its “kitchen sink realism,” This Sporting Life received praise and accolades from international audiences (including two Academy Award nominations for its leads).

18. Ivan’s Childhood (Dir. Andrei Tarkovsky, 1962)

After making a few brilliant short films, Tarkovsky ventured into feature filmmaking with Ivan’s Childhood, an adaptation of Vladimir Bogomolov’s short story “Ivan.” The film’s loose narrative structure uses dream sequences, flashbacks, and a war-torn terrain to tell the story of Ivan (Nikolai Burlyayev), a young boy who seeks vengeance against the German soldiers who killed his family.

The film garnered praise from international film audiences, even though Tarkovsky would openly criticize the final cut. In spite of the director’s criticism, Ivan’s Childhood is a compelling depiction of youth and violence, setting the stage for the illustrious career of the Soviet director.

17. La pointe courte (Dir. Agnès Varda, 1955)

In a seaside town, a man (Philippe Noiret) and his wife (Silvia Monfort) deal with the tattered remains of their failing relationship. The film intercuts between the specificity of the relationship and a globalized view of the inhabitants of the town. Inspired by the work of Faulkner, Varda’s first feature film takes a realist approach towards its fictional characters.

This style (which contains its own aesthetic flourishes) would heavily influence Varda’s fictional features, as well as her brilliant documentaries.

16. Reservoir Dogs (Dir. Quentin Tarantino, 1992)

Following a botched diamond heist, a group of men (most of whom use “colorful” aliases) try to figure out who is the undercover cop in the group.

The fast-paced, ultra-violent, and self-reflexive world of Reservoir Dogs laid the groundwork for Tarantino’s future endeavors, which would be known for their witty dialogue, their narrative experimentation, and their filmic references.

15. Shadows (Dir. John Cassavetes, 1959)

Shadows is considered by many scholars to be a landmark film in independent cinema. From its jazzy score and improvised lines to its controversial subject matter, John Cassavetes created a unique perspective that had rarely been explored in American cinema.

Though he would create a much more widely seen alternate cut of the film (Ray Carney is said to possess the only copy of the original cut), Cassavetes’ Shadows is a powerful depiction of American culture, showcasing the talents of one of America’s most ambitious filmmakers.

14. Night of the Living Dead (Dir. George Romero, 1968)

After suffering the shock of seeing her brother get killed in a cemetery, Barbra (Judith O’Dea) takes shelter in an abandoned home. There, she meets a host of characters who are all trying to survive the onslaught of zombie attacks.

This is the mother of all zombie movies (though that title would be usurped by Romero’s 1978 film, Dawn of the Dead). Romero creates a tense atmosphere and interesting characters that stand the test of time. Its “indie” feel and its unique creatures helped create a new zombie trope, one that would be used (and often abused) by countless directors.

13. Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (Dir. Mike Nichols, 1966)

George (Richard Burton) and Martha (Elizabeth Taylor) host a night of sadistic games with a young couple, Nick (George Segal) and Honey (Sandy Dennis). Their drinking and verbal abuse take their toll, and by the end of the night, the couples are at one another’s throats.

Nichols began his feature filmmaking career with a bang, not only challenging censorship regulations, but also taking a power couple and stripping them of their glamour. The film would win Oscars for Taylor, Dennis, and its cinematographer, Haskell Wexler.

12. Sex, Lies, and Videotape (Dir. Steven Soderbergh, 1989)

Soderbergh began his career with the brilliant Sex, Lies, and Videotape, an intriguing examination of an impotent man (James Spader) who records women while they discuss their sexual experiences.

The film not only put its distributor, Miramax, into the national spotlight, but it also showed Soderbergh’s unique talent of blending art house techniques with commercially viable actors.

11. The Night of the Hunter (Dir. Charles Laughton, 1955)

The Reverend Harry Powell (Robert Mitchum) has a penchant for killing his wives, but when he marries Willa Harper (Shelley Winters), her two children – John (Billy Chapin) and Pearl (Sally Jane Bruce) – prove to be too clever (especially because they are hiding a large sum of money from their stepfather).

Laughton’s directorial debut is an expressionistic thriller whose horror is generated as much from Harry Powell as it is by the shadows splashed across the walls. It is a brilliant and influential film that tanked at the box office, but has since developed an audience that appreciates it for its cinematic quality.