Boycott Hollywood horror until they get it right. Don’t give them any more of your money. It’s cold this winter, so put your money to better use, and burn it for the warmth. Or, better yet, give it to people who made giallo, who actually cared about thrilling you! They established the slasher genre, invented tropes for the sole purpose of toying with them. They worked in a genre that, like most subgenres of the Western, adhered to strict guidelines in order to give greater importance to seemingly small variations.

Where Hollywood would seek to repeat the success of the villain’s straight razor by ensuring all future villains have and do the same things with said weapon, giallo directors would see its success and try to top it the next time by toying with the glare on the blade, slashing vs. slicing, using a fake razor to fake a death, or simply tapping the blade on a hot light bulb for the “he cut the power!” trope. Gialli sought to thrill on a budget, and like the censorship and budgetary constraints on emerging films noir in the 40’s, depriving talent of water forced their vines to grow deeper.

Since the vast majority of giallo were made to meditate on a few specific thoughts, many movies not on this list are equally as valuable to learn from and are as enjoyable to watch. Also, many directors have multiple giallo masterpieces to their names, and a list of ten movies from two or three directors would be unforgivably narrow. Gialli, and movies in general, do not get too much more thrilling than the following:

1. Tenebre (1982, Dario Argento)

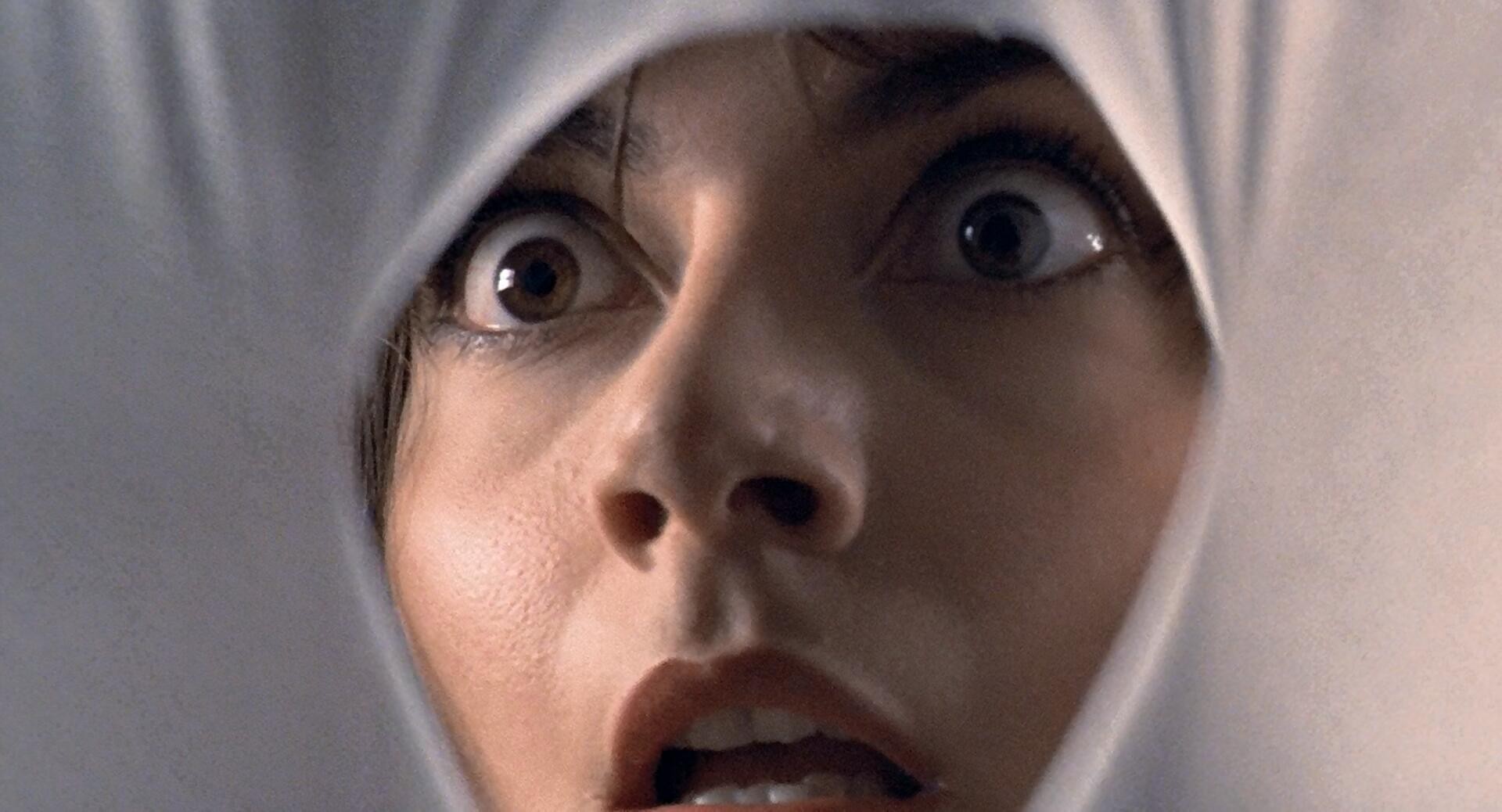

When thinking about the rest of Argento’s work, one usually imagines the black of night, but Tenebre is a “white” movie, through and through. Most of the scenes take place during the day, the actors wear bright colored clothes, the interiors are inspired by the 80’s cocaine addiction. While it would be easy to say that this undercuts any hope of being scared, that misses the point.

Goblin, the frequent collaborators on Argento soundtracks, created as thrilling a score for Tenebre as John Williams ever did for Spielberg. It’s as iconic as the Superman theme, but funky, and in a minor key. The audience is not meant to be scared, as much as they are entertained, a la Thriller. With this one aspect of the movie alone, the music serves to underscore that visual undercut.

As for the plot, well, you may be surprised to find that an American travels to Italy only to find murders surrounding him. This tourist becomes an amateur detective and almost gets himself killed in the process. And you won’t believe who the killer is. As always, Argento’s mission is to traverse the well treaded minefield of horror, exploiting any hidden live bombs he finds along the way. He always has a soft spot in his heart for misinterpreting past events.

“That thing that I witnessed; did I hear it wrong? Did I see it wrong? What piece of the puzzle am I missing?” The biggest asset he has here, as used in The Bird With the Crystal Plumage, is that the reveal has always been the mission from the get-go. The audience knows full well that there is something they’re not getting, that the joy is in the process of getting there, and that the satisfaction is getting it wrong.

Too often, binging on genres will put a checklist in your lap. How well did they do the falling heroine? How many boo-scares did we suffer through? Was the reveal the person we expected it to be? If the movie passes whatever criteria you have, then it passes; if not, it fails. But Tenebre really is not about the checklist. It fails the checklist. The checklist belongs to Opera, Phenomena, and Inferno, all of which would pass with flying colors.

Tenebre, like Deep Red, is about the joy of watching movies. Straight razors tapping a naked light bulb. Watching a couple in love from a distance, and slowly realizing you’re watching them break up. A murder in broad daylight, in the middle of a crowd. Tapping your feet to the rhythm of a psychopathic rampage.

At a certain point, it’s depressing to compare these cheezy movies with big budget Hollywood horror. These Italians had a budget of around twelve dollars, and all it took was the desire to be creative to make something worthwhile.

2. Don’t Torture a Duckling (1972, Lucio Fulci)

The camera is always moving, circling a character, looking up from the desk or following somebody in and out of a room. The editing is tight, cutting when the audience has received barely enough syllables to make the necessary inferences. Scenes start when the action does, and end when it’s over. This approach alone is enough to make the viewer feel like they’re watching it on a treadmill. Fulci doesn’t rely as much as Argento on extravaganzas of color. His expertise is the art of pacing and timing, none of which requires pushing the budget envelope.

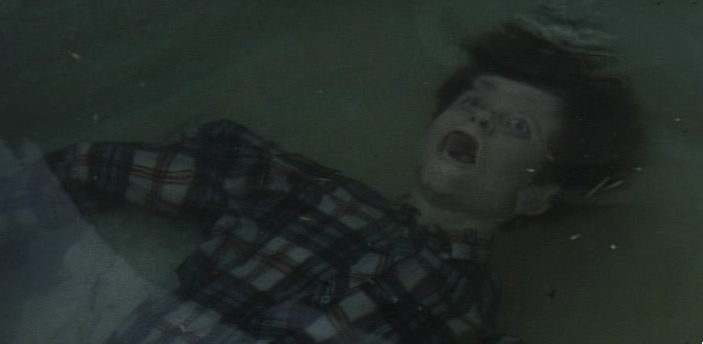

One scene in particular evokes the grand scope of a Leone spaghetti western, infused with the sadism of a slasher movie. A suspected killer is set free by the cops, and runs into an abandoned courtyard, stalked and cornered there by the victims’ fathers. No words. Someone turns up the car radio, and she’s massacred to a tune. It only takes five or so strikes. A hand slammed into a gate, a chain to the belly, a chain to the mouth, a machete to the shoulder… and they walk away. She manages to crawl back to the side of the road, and dies as cars pass her by, in plain sight.

This is what film noir production was all about. Giving small budgets to big minds and telling them to dance around the censors. Giallo was much the same, as evidenced here. That scene, from a production standpoint, cost a little bit of make up, the fee to shoot in basically a ditch, and a trip to Home Depot for a chain.

The big lesson to be learned from Don’t Torture a Duckling is that you can have your tropes and eat them, too. You just have to be allowed to tinker. It’s essentially a police procedural whodunit, with ever mile marker done differently. The protagonist, a reporter (of course), is introduced by being ushered out of an interrogation, a minor annoyance even to the scene he was in. He slowly creeps into the movie as the audience figures out for themselves that he’s the one to root for.

The murderer turns out to be someone not terribly surprising, so their death sequence picks up the slack. It involves falling off a cliff with some kind of magical sparks flying off their face every time it bashes into the rocks on the way down, intertwined with their life flashing before their eyes to solve the question of motivation.

These movies are not, to paraphrase Salieri, obos, high above the rest. These are movies with problems to solve, made by artists whose genius is realized through hard, consistent, passionate work. Don’t Torture a Duckling oozes with passion, a strange but welcome feeling to get from a murder mystery.

3. Blood and Black Lace (1964, Mario Bava)

Okay, Universal. Fantastic Four: Edge of Tomorrow Never Dies a Soft Origins of Ultron isn’t working out. You’re over budget, behind schedule, and you fired your director. What do you do? You call Mario Bava, a man known to take over projects with no script and complete them in mere days. A man who borrowed foam rocks from another set, borrowed a fog machine, and made a sci-fi classic from it. There are people who can get things done, and when allowed to step into the spotlight, will give you Blood and Black Lace.

Bava invented the giallo movie a year prior, and popularized it with this one. Before moving onto inventing the slasher, he traced the entire perimeter of the giallo, from gothic German castles to noir city streets. Bava knew how to make everything from nothing.

In Blood and Black Lace, the narrative is fairly well treaded territory, but the movie is fresh and alive! He bathes his walls in lights with colors absurd enough for Umbrellas of Cherbourg, but they all serve to get the audience in the mood. This is a fun, jazzy thriller. In fact, if there is any connection at all obvious between he and his protégé Dario Argento, it’s those impressionist lights, and the peppy score.

Where common knowledge says that the more you show your horror villain, the less interested the audience is, Black Lace flips that on its head. It takes effort for him to complete the murders. Which one is he? What’s the motive? Is he even enjoying it?

While giallo would later be known to be, among other things, a sexist genre, Black Lace anticipates it and answers concerns by placing a few female characters in patriarchal positions, levelling the sexes’ playing field not by exalting women, but by pointing how similar we are when put in the same greedy positions. Everyone sucks when given enough power.

4. A Bay of Blood (1971, Mario Bava)

The early 90’s saw hip hop fans wearing jeans backwards, trying their hand at skateboarding, and toying around with vocal leases like “-iggity” at the end of every other word; unthinkable today for a genre whose tropes are more solidified twenty years later.

In the same vein, the joy of watching movie subgenres grow lay in the wide open fields of the early years, when any- and everything is on the table. The slasher movies audiences know today rely on forty years of trial and error, in a misguided effort to rid themselves of the error. The error is half the fun; it shows the movie makers are as interested in their work as the audience is in enjoying it.

Bava’s landmark movie Bay of Blood distanced itself from the typical giallo, and in doing so accidentally helped spawn Halloween, which helped usher in, you know, the modern American horror movie. Bava made the original sexy-teens-in-a-cabin-on-the-lake movie, complete with smoking weed and promiscuous sex. But he knew even back then that this soon to be convention was only the set-up for the punchline. He did the thinking for future slasher directors who missed the joke entirely but kept telling it anyways.

The teens are pointless. They’re never fleshed out, and the viewer never really gets to know them. Their only function in the movie is as vessels for great death scenes, so why put forth energy establishing Breakfast Club characters? Why create empathy for the villain by explaining his origin story ad nauseam? That’s not scary. Bay of Blood is about the thrill of a death scene, the joy of the big reveal at the end, the process of manipulating emotions along the way.

The plot centers around adults with adult problems. The killer doesn’t attack you from your dreams. There are a lot of killers, but it isn’t a kill-for-a-good-harvest movie either. Everyone has specific individual motivations.

Bava used the camera for slow pans and dollies from as far away as he could inside a cabin specifically chosen for the many walls and halls that eat up square footage, allowing a grand scope in confined cabins. It creates an awe that isn’t scary. Solid popcorn tossing stuff here, and a testament to art from adversity, which John Carpenter would perfect a few years later with Halloween.

5. Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion (1970, Elio Petri)

Start the scene when the action starts, and end it when it’s over. Give the audience the fewest possible syllables necessary to infer what’s going on. The pace in Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion is as brisk as the protagonist needs to think, since he’s the chief of detectives tracking a murderer, who happens to be him. This reversal of the whodunnit quickly nabs the audience’s attention, which is sustained throughout by watching his cool veneer implode.

Elio Petri makes a smart choice by wrapping the narrative around a political feud between the communist youth and the socialist adults, while not taking a stance one way or the other. The dangers of youth come from letting their bleeding hearts run too far, and the dangers of adulthood come from reigning it in too tight. The advantage Petri gets from using the exact inverse of the traditional giallo narrative arrives at the climax.

A big hurdle horror movies constantly trip over is the boring expository ending. Giallo directors’ passions typically lie in overcoming these hurdles, and Petri’s is the most effortless you’ll ever see. By taking the inverse, his killer feels compelled to be caught, finally is, and no one believes him. He’s too big to fail. He is above suspicion even when those suspicions are confirmed, renounces his admission after being prodded to do so, and resumes the mission to find the murderer. After all, he’s still at large.