5. The Leopard (Luchino Visconti, 1963)

Often compared to Gone with the Wind even at the time of its release, this Italian film by one of the great lesser-known auteurs, Luchino Visconti (Who had made his other biggest film, Rocco and His Brothers, just three years prior) definitely shows his influence with this film, what with its gorgeous color visuals, epic ambition, and a sense of anger and bitterness not common for most mainstream films at the time.

But remember, this was a time where Gone with the Wind was regarded as possibly the greatest and most successful film ever made. It was released in 1939, and was re-released in some fashion every decade since, it won eight Oscars and was nominated for five others, receiving a comparison to Gone with the Wind, even in 1963, was a huge deal.

But The Leopard was a different story. It certainly had its fair share of fans, it did well at the French box office, and Cannes Film Festival even awarded it the Palme d’Or. But on the other hand, a lot of critics dismissed it as pretentious, and many were critical of Lancaster’s performance.

Recently however, the tides have shifted for the two films. The Leopard kept gaining a reputation, and with filmmakers like Martin Scorsese claiming it was one of the greatest films ever made, a reevaluation was inevitable. It’s now regarded as a classic, and it’s still growing in popularity. Gone with the Wind, however, had the opposite occur. Many modern critics feel the film is melodramatic, unlikable, overlong, and boring. While it’s difficult to remove so much hype from such a massive film, Gone with the Wind has been steady in iconography, but decreasing in public opinion.

These two films make a great pairing because, despite its ambition, Gone with the Wind is held back by the flaws of older cinema. Every scene is melodramatic to the point that the most emotional scenes don’t feel like that much in comparison. Perhaps why so many find it boring is that, for all the things Gone with the Wind does right, subtlety and variety were not considered at all. It’s ambitious, but dated.

For all the reasons Gone with the Wind has fallen out of critical favor, The Leopard succeeds in the same categories. It’s similarly ambitious, but is propelled by a more modern filmmaking style from Visconti. While its visual style is always out in the open, with its bright colors and costumes, the characters aren’t explained by individual scenes, as much as a slow build-up of moments, and revealing dialogue choices.

It’s a film where your attention is rewarded, and scenes always have more than one purpose. If there was something to discover in Gone with the Wind, it would spell it out for you through exposition or a brief but obvious visual cue.

You’ll find The Leopard really did usher in a group of less ambitious, but extremely calculated and dark films from the 60’s and 70’s. From The Conformist to The Godfather, subtlety slowly became a strong selling point for arthouse films, even if the ambition still shines through.

From that point on, the mentality for sprawling arthouse epics seemed to change from a celebration of new techniques changing dated storytelling techniques, to how strong scripts and stories can be amplified by a less restricted atmosphere.

The Leopard was certainly not the first film to incorporate subtlety in an otherwise ambitious product, but it showed how far you can go with such a large scale, without devolving into constant melodrama and easy exposition.

So while the sprawling epic may be a thing of the past for film, The Leopard lives on within a lot of the greatest large-scale filmmakers of modern day cinema.

4. The Battle of Algiers (Gillo Pontecorvo, 1966)

One difference that’s extremely evident between popular old films and popular modern films is older films often earned popularity from spectacle, whether it was the free-flying war films like the silent film Wings, or the early sound film All Quiet on the Western Front, to the more melodramatic bunch, including Gone with the Wind and How Green Was My Valley. But in recent years, this type of style has grown out of favor, and instead we kept some of the ridiculous stories and tropes, but set them to more gritty and realistic styles.

The regular genres were affected by these changes, but most notably with these changes came some new sub-genres/movements. From “Mumblecore” to “Found-Footage”, viewers nowadays seem to appreciate a fresh take on modern day ideas, like home-footage that features something horrifying.

This gritty-realism tone was used sparingly before 1966, but during Italy’s experimental 1960’s, a documentary filmmaker named Gillo Pontecorvo kept that documentary style of grittiness, but put it towards his second fictional feature film, The Battle of Algiers.

The film depicts Algerians who stand up for their independence against the French government. The film goes deep into both sides of the fight, strategies are shown in extreme detail step by step, without always informing you explicitly what the outcome will be, which adds to the replay factor of this film.

Unlike many of the films on this list, The Battle of Algiers was actually very well received when it was released. There were detractors, but they were the vocal minority that was drowned out by the praise of Venice Film Festival, the Academy Awards, and dozens of critics.

The reception has only grown stronger since its release, and from the beginning it was a big influence on a change in the usual film formula, both in arthouse and mainstream productions, with both growing more dark and closer-to-reality. Whether you prefer this new shift, or the older formula, The Battle of Algiers hasn’t aged a day, and is a good film to show people who largely avoid older cinema.

3. Breathless (Jean-Luc Godard, 1960)

Both Godard-obsessed monsters and Godard-hating heathens (Equally horrifying) can at least agree that Godard, for how insane of a man he is, he inspired dozens of fantastic directors, and he never felt cliched or boring.

Art film before Breathless sometimes fell into a vacuum of boredom, where ambition began at costume design and ended at music. There are definitely exceptions to this, but even those films were attempting to out-match the impact and seriousness of the last. William Wyler, David Lean, George Stevens, Henry King, all good directors, some great, one or two of them wouldn’t look out of place on a list of the best.

But while this flaw was almost undetectable in their best films, it was very obvious in their worst. Overdramatic three act structure with actors either exhausted or bored, you can tell there was a formula to every one of their films, and how often that formula succeeded depended on the talents of the director.

The French New Wave had a big part in changing that. Even before Breathless, there were multiple films from the movement that are recognized today as a strong part of film history, including Agnes Varda’s debut with La Pointe Courte in 1955, Claude Chabrol’s Le Beau Serge in 1958, and of course, Francois Truffaut’s magnum opus, The 400 Blows. While all of these films were beautifully experimental, Breathless was more fast and free-form than most films in the 30 years before its release.

From its famous fourth-wall breaking, to the infamously constant and almost-random editing, and the dialogue which flows between sophisticated and eloquent, to confusing and out-of-place. This was a trend Godard used in a lot of his films after, but Breathless was where many of these trends began, for him at least.

Godard’s meter of craziness kept jumping up and down throughout his career, whereas something like Vivre Sa Vie was slow and well thought out, Contempt was wickedly uncompromising. You could argue these films are better than Breathless, but Breathless managed to be the most defiant of film tropes.

It doesn’t even feel like he was borrowing from the previous French New Wave films, which perhaps make Godard the “Waver” that stood out the most. This perhaps made his experimentation more commonplace in recent films.

Dramas and comedies alike break the fourth wall, avant-garde cinema took inspiration from Godard’s odd dialogue choice and editing, even some of the worst films to come out in the past decade have to owe something to Breathless, whether they liked it, hated it, or haven’t even seen it. But we all feel its presence.

2. Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960)

A lot of these choices are listed because of them fitting alongside more recent films well, whether it’s a recent trend which took inspiration from an older source, or it did something that took a while to really take effect. Psycho, and most of Hitchcock’s films, are different. They can fit alongside every year, because no matter what year you look at, everybody has tried to do what Hitchcock does, and most of the time, they fail. This was true in 1960, it’s true now.

Hitchcock had a gift for the unexpected. Reading a summary of his films is pointless, as they often make his films out to be predictable, which by the premise alone, is the case. His stories are so obvious, it would ruin any director who took them on.

But watching his films, Hitchcock hits you with twisted moments of doubt, subplots that deceive viewers into thinking a character or scenario is more important than it actually is, you doubt your original instinct, even though it was painfully obvious in the first place. Hitchcock tricks you into thinking the way he wants you to think, but the facts are still right on the table. You feel like an idiot when the surprise is revealed, but Hitchcock doesn’t lie to you. He just leads you in another direction.

Bad directors, back then and now, would try this in their horror/suspense films. Mislead you into thinking something, when it was actually the obvious choice you should have suspected. Instead of hiding what’s in plain sight, however, they deliberately lie to you. Take the 2010 film Devil for example. (Spoilers for Devil and Psycho) Several characters are trapped in an elevator, and they begin dying one by one when the lights go out. Near the end, two are left alive, so you’re forced to believe one of them did it.

But it’s revealed one of the dead characters is really the devil, and killed the others. It’s not like the devil thing was a surprise, as it’s in the title, but there’s no mention that the devil could have been one of the dead people. If you actually guessed the ending to Devil, you’re an insane person. But with Hitchcock, he does his best to make sure you consider the real ending, but dismiss it in favor of something different.

Which brings us to one of his greatest achievements, Psycho. Perhaps his most iconic film, Psycho tricks you every few minutes, which just makes the horror feel more unpredictable. We’re tricked into thinking Janet Leigh is the main character, and she dies early in the film. The last person she interacts with becomes the main character.

We think the killer is a woman, but the crazy guy is just really into cross-dressing. We believe the crazy guy is interacting with his demanding mother, but really he’s been acting as and for his mother as she’s been dead for years. It wraps up in a way you expected in the first third, the motel owner is crazy and gets locked away after killing some people, but how Hitchcock turns that premise on its head throughout is jaw-droppingly impressive.

It’s a shame so little people could do what Hitchcock does with deception, but you could argue Hitchcock was not only ahead of his time, he was ahead of our time too. It’s hard to say if this is just a flaw in film that’ll be fixed in time, or something only Hitchcock could master so well. Either way, the mere fact we’re asking that question proves Hitchcock’s directorial talents.

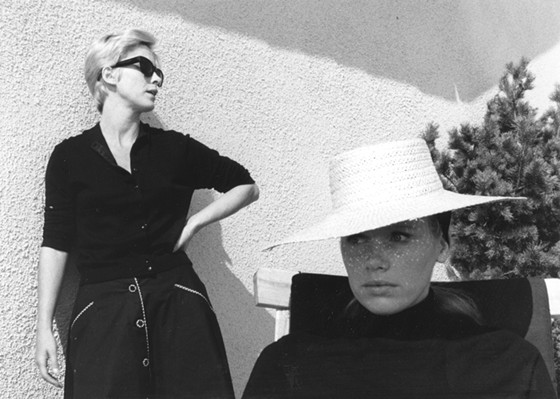

1. Persona (Ingmar Bergman, 1966)

Avant-garde cinema has not been a recent trend, if any of the other films on this list don’t tell you already. Even as early as the 1910’s, experimentation and working outside other’s comforts zones has been rewarded and insulted equally, from the absurd shapes and shadows of German Expressionism and the uncompromising speed of Soviet Montage, to nowadays with Mumblecore and Found Footage, among other movements and styles. Despite these examples, Persona was something unheard of in 1966, even the strangest works of the 50’s and 60’s were distant from this anomaly.

Ingmar Bergman himself never strayed away from philosophical ideas and psychological examination, most of his films dealt with one or both of these topics. Even taking that into account, Persona is an odd film, even for his standards. The opening and closing scenes only connect with each other, as the connections with the rest of the film are loose, only featuring brief images of the two main characters. The film deals with the concept of a nurse who finds her personality is melding with one of her patients, an actress who cannot speak.

Explanations are a rare thing in this film, almost everything is up to viewer interpretation. A basic plot is given and characters are developed from haunting visuals and strange conversations that often feel very vague. Bergman gives a lot of space and time in his visuals for you to take them in, but that’s all you get. Whether something is literal, a metaphor, or something in the middle, most of that is up to you. There’s almost nothing set in stone here.

This vague, hard to interpret way of presenting a film has grown in favor substantially since Persona, with directors you may recognize like David Lynch, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, or Tsai Ming-Liang, all filmmakers who, at one point or another, used this formula perfected by Bergman towards their vague, hard to follow existential dramas.

It’s no longer surprising to have to dig deep into a film just to find the bare minimum when it comes to its meaning, or message, or even something as simple as its plot. And even with all of this advancement, improvement, and a culture that pays and watches these films which has increased its popularity, Persona still remains one of the most difficult to comprehend and personal films ever made.

Author Bio: Patrick Bowering is a Newfoundland film hobbyist, who has been passionately viewing a variety of films for the past half decade. He is especially experienced in the silent era of film, as well as the French and Iranian New Waves.