6. Thresholds

Almost repetitively, Antonioni’s characters look in or out through the threshold of some kind of entrance, whether it’s a door or a window. This mode of framing the character is a way to describe the existent distance between two subjectivities, defining an internal space as an intimate territory of one specific character, making any other character an invasive figure.

There are numerous examples of framing a character in the threshold in “Il Grido” and the final sequence of “Profession: Reporter” can be a perfect example.

In “L’avventura”, the scene where Monica Vitti (Claudia) looks in while waiting outside of house for her friend is a meaningful mise-en-scène. She’s located outside of an intimate relationship between Sandro and Anna; the dramatic weight of the scene gets more notable as the narrative flows, as Claudia starts a relationship with Sandro and practically takes the place of her missing friend.

7. Eliminating color to emphasize form

“Blow Up” is in color, while the photos where the character is searching for a sign of “the incident” are in black and white. It’s a mode of flattening the whole visual context and then only bringing out one element that formally and visually stands out.

Even if some works of Antonioni are in color, they are mostly de-saturated. Representing a low contrast picture and flattening the visual texture is a notable element in Antonioni’s filmmaking style.

8. Photographic compositions/the importance of background

Whatever is in the background in the shots of Antonioni’s films, it’s by no means a passive background. In “Blow Up”, as the profession of the character justifies it, the characters generally stand before a plain colored surface.

In “Blow Up”, Antonioni has used this fact as visual assistance in representing and developing the unspoken characters. Jane (Vanessa Redgrave) has lots of secrets, though apparently is ready to start an intimate relationship with Thomas (David Hemmings), because he is now the one she’s unwillingly sharing her gravely important secret. She doesn’t even reveal a word of her past or the incident in the park.

Nonetheless, Antonioni’s mode of representing Jane’s character is a plain violet paper screen that Thomas chooses as her perfect color, while the rows of models who are covered with colorful customs and makeup. The background is a layer of transparent surfaces, and the young girls who don’t have a specific color and just roll in the colored screens, can tell a lot about the indecisive and still unformed characters of the girls.

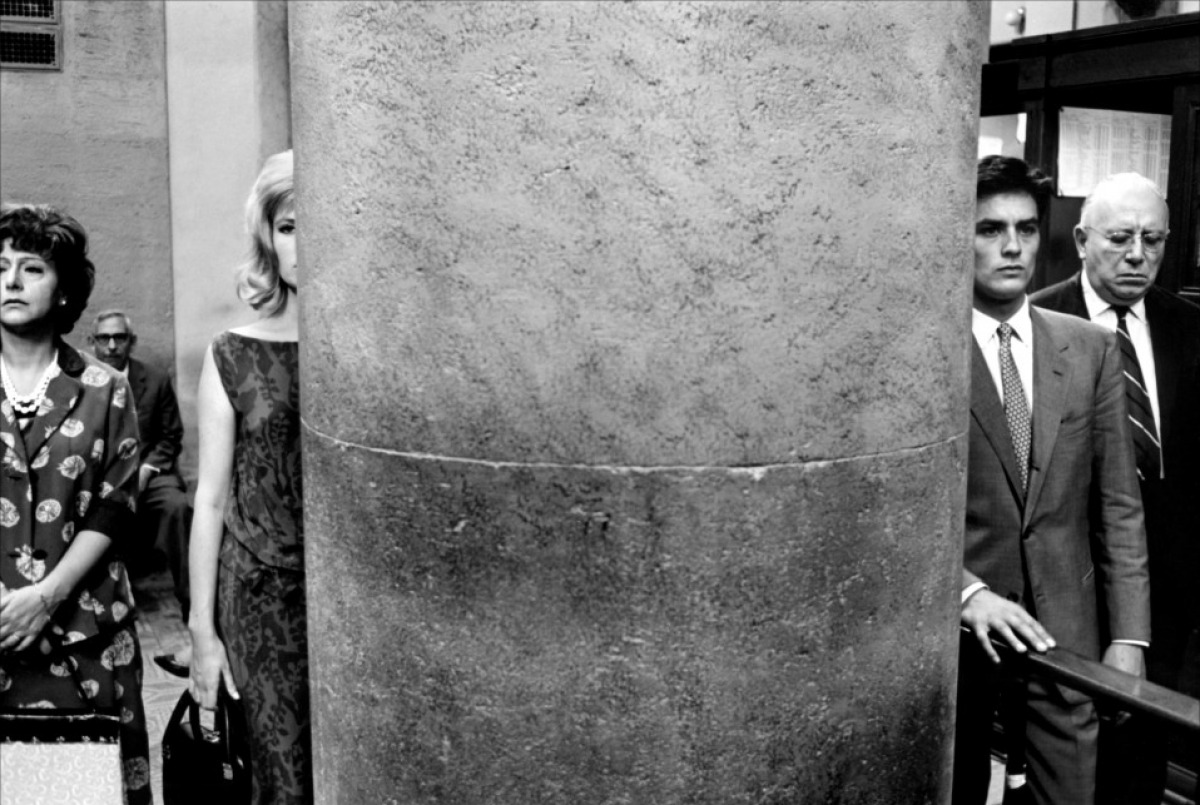

9. Blocking the figures

Instead of getting closer to a character to take a close up or cutting the whole figure of the character, Antonioni keeps blocking their aspects with an architectural element, like the column that blocks the full shot aspect of Alain Delon and Monica Vitti in “L’eclisse”, or the row of models in “Blow Up” where each model blocks the one behind her. This fact can be easily interpreted as the part of character that doesn’t come out or is not freely expressed.

Gus Van Sant uses the same narrative method to get closer to his characters, which is specifically notable in “Gerry” (2003) as he prefers to restrict the visual camp instead of physically getting closer to the subject.

10. Absence

After introducing the character in an ambient setting, Antonioni keeps eliminating the presence of the character to create the sense of absence.

Much like showing a corpse in the park, later for it to disappear unexpectedly, or introducing a character as a main character that gets lost at the very first sequences of the film (“L’avventura” and most importantly, the final scene in “L’eclisse” where the characters do not show up at the appointment). It’s all about what the filmmaker decides not to show or narrate and leaves it as an open choice to his audience.

There’s this perfect scene of the couple biding their time in a night bar that says it all about Antonioni’s philosophy. Giovanni (Marcello Mastroianni) and Lidia (Jeanne Moreau) are just sitting there, wordlessly watching an odd performance from a dancer who dances with a glass of wine without wasting a drop. This is a conversation scene, only the subject of the conversation is the thought that Lidia has and doesn’t want to talk about it.

The dialogues reveal the fact that there is something that the character refuses to utter. This conversation is what real life is: it’s boring with lots of points that remain silent and maybe they won’t be ever expressed. What the audience expects from cinema is the dance of the woman with the glass of wine. What Antonioni is trying to say in this scene is this: you want to be entertained? I give you a circus; but the silent tiresome is real life, it still remains in the background and nothing is going to change that.

Author Bio: Maryam Raz is a freelance filmmaker and screenwriter. La Mite based on The Gentle Spirit of Dostoyevsky is her most recent work.