It’s a black hole. Its job is to consume, and the best you can do is look to the event horizon to admire what hasn’t yet been destroyed.

Hollywood wasn’t always this way. They gladly incorporated German expressionist directors into the fold, stirring them with hard-boiled novels to produce film noir, one of the U.S.’s great contributions to the world. They let young, hungry directors fly under the radar and stumble into the new era of New Hollywood. But they also handed John Woo an apple and told him that God wouldn’t mind him making Broken Arrow. They saw Yuen Woo-Ping’s choreography in The Matrix and are still pushing that button to this day in superhero movies.

Apparently, the Wolverine is adept at both Southern style Shaolin kung fu, hung gar, and Northern Chinese Opera style acrobatics. And samurai stuff, too, because it plays great at test screenings.

What these modern action movies tend not to realize is that they’re pushing buttons, not boundaries. They’re children saying, “Boo!” a hundred times to their dutifully scared parents. With each successive Hong Kong movie John Woo made, he found success experimenting with a formula.

Instead of Hollywood asking him to experiment with them, they asked him to keep writing the same formula. “Do that, but in Mission: Impossible!” “Do that, but on a train!” “Do that, but with faces!” “Boo! Mommy… Mommy… I said, ‘Boo!’ Boo, mommy! Mommy!” Alright! Jesus. These movies all carry specific traits that Hollywood can reproduce to consistently great action movies on the cheap.

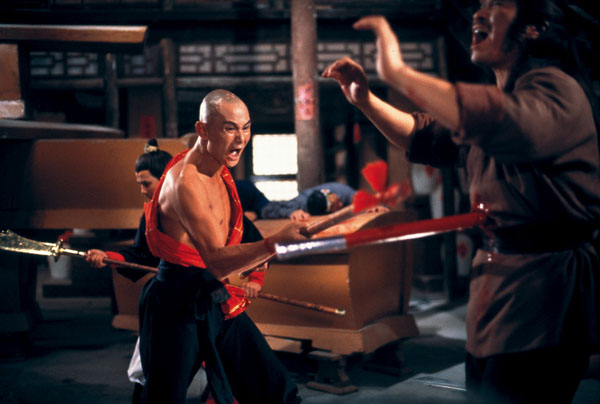

1. The 8 Diagram Pole Fighter (1984, Lau Kar-leung)

Lau Kar-leung made it his mission in life to transfer real-life martial arts to the screen. His movies usually begin with an actor on a soundstage, with a blank background, simply performing the styles that will be shown throughout the movie. Some of the plots are little more than an excuse to showcase how said styles interact.

A Chinese man marries a Japanese woman, and they quarrel about which country’s martial arts are better. A leader disbands his faction of martial artists, is attacked by assassins, and must defeat them by using every historical weapon available. Uh huh. By necessity, though, he perfected the great staple of the action movie: the training montage.

In Pole Fighter, Gordon Liu’s family was ambushed, and his brothers (save one) and fathers were killed. He seeks refuge in a Buddhist monastery. The monks there do not want him, as he is full of anger, and when displaying his martial arts, they note that every strike is a lethal one. He practices their methods, using a pole instead of the spear he’s used to. On wooden wolves, he learns to “defang” instead of kill, developing an “8 diagram” style.

Of course, there is a final showdown to test his newfound tranquility. The point is, he is both testing himself, his society’s supposed values, and figuring out if there is an acceptable middle ground between the two. The terrifically violent ending offers no clear stance. But Lau had created a three tier system of making movies.

In Pole Fighter, Lau takes the inverse of Master Killer’s staccato feel, and tailors his edits to a flowing feeling that reflects the values Liu should be absorbing. Instead of a highly structured training montage that leads to the expected conclusion, Liu just kind of ends up at the monastery. He develops his style by puttering around a pond for a while, and fiddling with vines. he inserts himself into a training session that’s already underway, and no one really wants him there.

He’s not exactly part of the monk clique by the time his newfound values are tested, and the monks aren’t really sure if they should help out or not. He learns not to kill and only defangs the villains, but it’s so violent that the audience is unsure if he really learned the point of it all. Everything’s up in the air.

Could The Wolverine 4: Shrek Vs. James Bond: Redemption Never Dies learn a lesson from this? If, as a culture, Americans value the superhero story by throwing their cash at it, the values reflected are embarrassingly simple: the world is in danger, save the world. What motivation does Thor need to use the hammer other than, “Audiences want to see that hammer. Let’s get three more hammer sequences in the works.”? Well, none, because audiences aren’t asking for anything more.

But audiences didn’t ask Lau Kar-leung to be an auteur. He just was, and died with a catalog of action movies widely considered to be among the best ever made by those who care about action movies. These are tangible, reproducible methods that are only dead because no one knows to revive them.

2. The Prodigal Son (1981, Sammo Hung)

This will be the only entry that is a plea to make R-rated action movies. These, in particular, are cheap and make tons of cash. Just look at John Wick. Sammo Hung made some legendary kung fu movies in his day, none more hard and brutal than The Prodigal Son. Even as a period piece, it must have been dirt cheap to make.

An old theater, some huts on a dirt road, a field with some old concrete structures whose sole purpose was to eventually crumble… nothing fancy in Prodigal Son, which means the rest is left up to creativity. Film noir flourished under budget constraints. So did Hong Kong kung fu. Is it so infeasible that young, cheap, hungry movie makers could crank out a movie that earns a 4,000% profit?

The Prodigal Son takes martial arts seriously. Sammo was always dedicated to authenticity, and was willing to use his chubbiness for laughs to do it. No one is laughing by the end. In what is a thinly disguised soundstage, the actors (who also doubled as stuntmen and choreographers) gathered up some stage blood and makeup, rolled camera, and left the polish to Sammo.

As an accomplished director himself, again like the noir directors, he was able to light and film his sets in a way that turned cheap surroundings into mythic stadiums for his gladiators. How is no one bottling this magic?

3. Dragons Forever (1988, Sammo Hung)

Jackie Chan was willing to die for a spectacle, and almost did on several occasions. Neither Hollywood, nor the world itself could ask a person to do what Jackie did for entertainment, which is why he is such a rare breed. He asked to do it, and his friends signed up, too. It’s no secret that Hollywood specifically designs action sequences to stay well inside the PG-13 limitations, by editing out the impacts of punches and kicks, and allowing as few puncture and slice wounds as possible to avoid blood. How are you to revive the action scene if their your contradict the nature of good action? Simple: you hire Yuen Biao.

Jackie and his brothers worked in a system that allowed little stunt flourishes by way of the hundred-take shot. If Yuen Biao needs to get up to a roof, and his ladder can’t reach the top, he improvises. While balancing on one side of the ladder, he flings the other side up, so that it falls back down on the roof, creating a bridge. Yuen is then, you know, really careful walking across. Or else he’d break his neck for an unnecessary fifteen second stunt.

Hollywood famously altered Jackie’s filming style by requiring more planning and fewer takes, the exact opposite of the system that allowed him and his friends to be so great in the first place. Would you ever find Hollywood Jackie sitting in a chair, kicking a dangling pencil off the desk, and into his hand without looking? Or would it go like this: “Alright, Jackie! Chris Tucker wants you to stay on the bus, but you don’t want to. So, as soon at the bus stops, you hop up on a street sign, and dangle there until we yell ‘cut!’ You’re brilliant, Jackie! Brilliant!”

Since the B-picture is no longer able to provide the training ground for moviemakers that it was during the 30’s and 40’s, maybe the cheap second units could fill in. If your star is too expensive to be allowed to run wild in second unit, hire a supporting cast of young, hungry up-and-comers. They’re the supporting cast to your action movie. Yuen Biao is not a household name, but the stunts he performed in Dragons Forever alone are enough to make him a legend.

People are still willing to put their lives on the line, and on the cheap. And none of it requires shedding blood or kicking ass (though it helps). The final fight of Dragons Forever is in another realm. It’s harder and more polished than a diamond. If you take out the blood, you’d still have stunt crew falling a story below onto concrete corners, spine first. Need to edit that out? Figure out a reason why Yuen Biao has to perform acrobatics around poles and hand rails. Make the floor lava or something, and force him to hop around.

These crews absolutely shine in second unit. In Dragons Forever, Yuen Biao gets out of a taxi, and needs to tell Jackie something so urgently, that as the taxi is pulling away, he jumps on and rolls over its hood. It takes exactly three seconds of screen time and probably required two takes.

But those little bits show that the filmmakers and actors care, and there are hundreds of them littered throughout Jackie flicks. You don’t have to spend a lot to show the audience that you love making movies. CGI is currently used as a Valentine’s Day rose, and for whatever reason, Hollywood has lost interest in the sex it sets up.

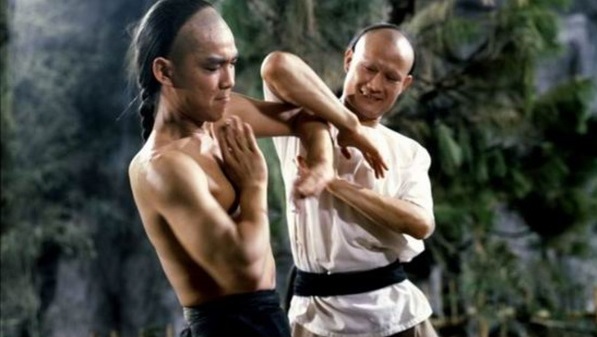

4. Clan of the White Lotus (1980, Lo Lieh)

The mystery of the villain typically requires that the movie show his abilities as little as possible. Clan of the White Lotus slaps that logic in the mouth, and flaunts Pai Mei at every opportunity. Lo Lieh frequently played the Pai Mei character, made known to the world through the Kill Bill! movies. He also directed a few movies, and showed that he was, in fact, skilled at that, too.

The movie is essentially a “castle breach” movie, where the castle is Pai Mei’s body. Gordon Liu has to kill Pai Mei, and spends the movie getting soundly defeated by him, learning bit by bit the key to eventually not losing. This is, then, a character study as well, where the character is Pai Mei’s martial arts. What makes it tick, and why?

Gordon Liu eventually learns that, to attain victory, he has to fight using a woman’s style. His strong, brash hands cause Pai Mei to float weightlessly backwards at every strike. His body seems to have no weak spot when it finally is hit. Liu has to learn to tailor his style to Pai Mei so that his hands and feet create absolutely no breeze, thus keeping Pai Mei close. Once he gets close enough, he must use acupuncture to strike Pai Mei’s, you guessed it, pressure points!

The legitimacy of the whole thing is laughable, which is the movie’s strongest advantage. When the audience is cued to laugh at the man using the sissy style, they realize that Gordon Liu is very serious. He looks feminine with his curved wrists and arms, but he never lets up, and gets better and better.

This supposed sissy style is something to achieve, to attain. He becomes a master of it through trial and error, an idea probably not lost on the American black audiences of the 1970’s and 80’s, who loved kung fu movies in part due to a non-white hero typically facing a similar discrimination that they were at the time.

The acupuncture bit is thrown in for entertainment purposes only, but it’s the key to defeating Pai Mei. Once Liu gets close enough, he litters Pai’s body with needles, rendering him unable to move. The gaudy color schemes of Pai Mei’s castle, the neon reds and greens coming from behind the grey concrete walls, only add to the absurdity. This is pure fantasy, exactly what a child would imagine when playing with toys.

Should Hollywood ever wish to have fun again (there’s no joke to make here; they literally made a gritty origin story of The Wizard of Oz), then Clan of the White Lotus could easily serve as an entry point. The fun is in having a conversation with the five year-old brain, and challenging it. Your male hero only becomes a master through perfecting a woman’s skill. Also, the hero keeps failing, and may never succeed, even at the end of the movie. A little bit challenging for a young boy, so indulge him with pressure point fights.

Action in Hong Kong used to be a playground for experimentation. These cheaply made movies earned high profits, so there was little risk in cranking them out by the hundreds every year. Hong Kong did the dirty work for Hollywood and found the winning formulas.

Sure, they would be B-movies today, but that only denotes the cost of making the movie, not the quality. Clan of the White Lotus was a cheaply made movie whose heroes and villains are currently standing the test of time, by proving that the stuff of myth and legend do not come with a huge price tag. They come with effort.

5. Master of the Flying Guillotine (1976, “Jimmy” Wang Yu)

Why not mix up some genres? Master of the Flying Guillotine operates as a wuxia pian as much it does a kung fu, a journeyman movie as much as a tournament movie. The big set-pieces of Guillotine have little to do with each other, and it’s okay. Mission: Impossible operated under the same logic, and like Guillotine, succeeded (in part) because those exhilarating set-pieces weren’t bogged down by the rest of the movie.

Wang Yu gives the audience the style match-ups, which he experiments with. Instead of local styles competing against each other, he presents a yoga master from India (yoga is, of course, known to be among the most savage of fighting styles), a muay tai expert, and a kobujutsu expert.

Wang further layers the story by making the movie a sequel to The One-Armed Swordsman, in which he also starred. So, now the protagonist is a master of one-armed fighting, another way to stimulate the action. The villain is a blind imperial assassin whose two students the one armed boxer killed in the previous movie.

The movie opens with his finding out the information and burning his home to the ground to begin pursuit. In the first scene, only the villain is introduced, and his motivation and rage garners a cautious sympathy from the audience. It also muddies the heroism of the protagonist. Further stimulation.

The villain quickly finds his bad-guy status buy murdering every one-armed person in the town in which the tournament will take place. He enters his mercenaries (the yoga, muay tai and kobujutsu experts) into the tournament in preparation for ambushing the whole proceeding. Once the tournament is ruined and the hero is being chased (the exact moment the audience fully warms up to the hero and cools off toward the villain), the set-pieces kick in.

The hero sets traps in a coffin-maker’s office, fights the bare-footed muay tai fighter in a locked hut with a heated metal floor, battles the master of the Flying Guillotine in a field designed to render the weapon useless.

Tournaments in movies usually act as old video game levels: get all the important characters in one place, and knock ‘em off one by one. Naturally, the last two men standing will be the best, so it’s a Final Boss stage. Wang toys with that idea as well, by shattering the tournament, and taking it to the streets. The rest of the movie is itself a tournament of sorts, where the opponents get more difficult, yes, but so do the levels in which they fight.

The big question of how to properly translate video games to the screen is thusly answered. As always, start with strong characters. Establish the logic of the video game by framing it (a tournament, a mission…). Once the audience understands and believes the logic, allow the story to work itself out by using that logic.

Video games always start with an easy introduction level that helps the player understand the controls. This is not to be confused with Act I. In Master of the Flying Guillotine, Wang wisely places the first level inside Act I, allowing the characters to be people outside of their function.