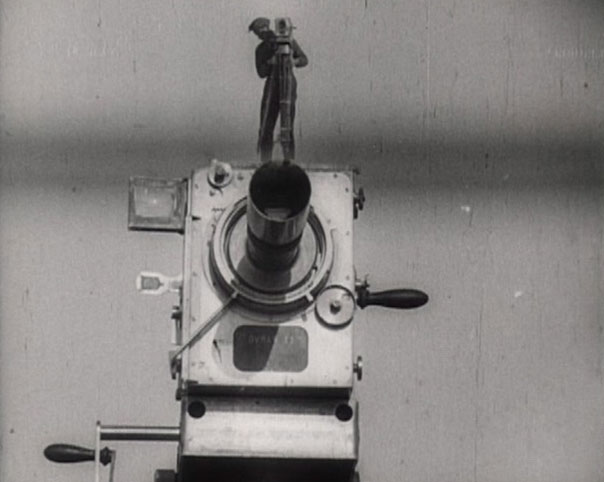

5. Man with a Movie Camera (Dziga Vertov, 1929)

A documentary by design and entirely experimental in execution, this revolutionary 1929 film is legendary for its impact on moviemaking. Groundbreaking documentary filmmaker David Abelevich Kaufman created the film, but under his adopted pseudonym Dziga Vertoz.

Man with a Movie Camera created and implemented dozens of cinematic techniques that were well ahead of their time. From slow-motion, to double exposure, dutch angles, split screens, and even freeze frames, Dziga Vertoz created a masterwork of intoxicating levels of technique. Vertoz created a film that was “characterless”, being strung together by an innovative self-reflexive style of the camera’s existence.

The style is fully aware that the camera itself is our guide to the world, through twists, turns, and abstraction. The lens becomes a window to view through. Great credit should go to cinematographer Mikhail Kaufman as well. Vertoz was a theorist on movie making just as much as a creator. He envisioned a world of pure documentary movie making, showing reality over story.

The film’s abstractions and erratic editing style illustrates a schizophrenic feeling and capturing the late 20s Soviet Union. The film is also entrenched in Marxist ideology with depictions of industry and labor forces. This leaves the film with a political message, but a unobtrusive tone.

The film can be so bizarre at times with its abstraction, even going so far as to show the process of a woman giving birth. Dziga Vertoz’s concepts and style were highly influential. He is credited as the inspiration for the Cinéma vérité style and inspired such greats as Jean-Luc Godard to reject convention. Vertoz set in motion a century of rule breaking for filmmakers.

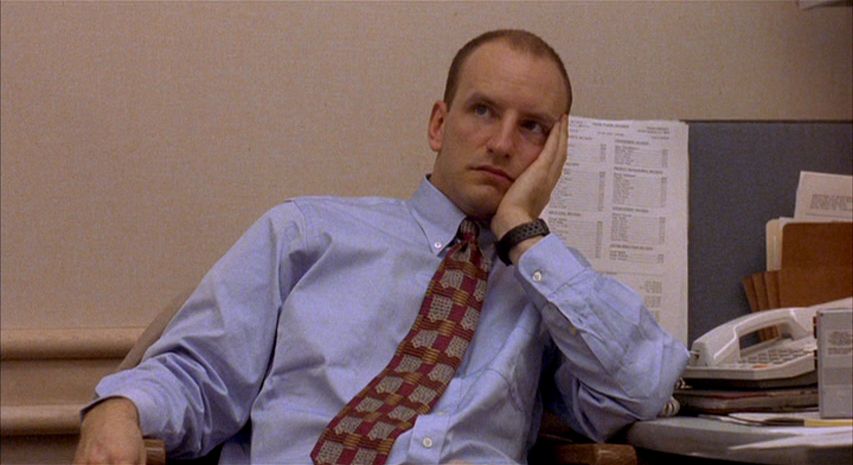

4. Schizopolis (Steven Soderbergh, 1996)

This film by director Steven Soderbergh is not just an off-the-wall approach to film creation, but a humbling diagnosis of the process. After his breakthrough with sex, lies, and videotape, Soderbergh made several other films under the studio system. In 1996 he decided to embark on a low-budget feature for himself. Soderbergh not only directed the film, but stared, wrote, produced, co-scored, co-edited, and even served as cinematography.

On a 250,000 dollar budget, Soderbergh created a non-linear and experimental comedy film with a love of confusion. The film has many non sensical “narrative” moments that creates a scatterbrained frame work. Soderbergh plays two characters that cross paths and even take over each other’s lives. There are subplots of heroin addicted brothers, an exterminator having sex with housewives, and even inexplicable shifts to Spanish voice dubs.

Some scenes repeat at random and miscommunication slowlys evolves to a possible theme. Soderbergh is said to have begun filming without a completed script, allowing for large amounts of improvisation. Steven Soderbergh’s film was met with very mixed reviews.

Alienating viewers in many different ways, the film has a low cult status. The film is hard to explain because it does not want to be simple. Soderbergh was going for a deliberately confusing, ruleless, and DIY film from audiences that were not prepared. This film is forgotten in Soderbergh’s career, but deserves examination and a bump in popularity.

3. Triumph of the Will (Leni Riefenstahl, 1935)

Propaganda is rarely examined as art. They are seen as dangerous forms of national control. By definition these are political pieces that are biased to its purpose and deliberately misleading. Academically, propaganda is said to be “used to promote or publicize a particular political cause or point of view”. These films have a troubling history, but can they be achievements in filmmaking? Triumph of the Will is an extremely difficult case for this question.

The film is a piece of propaganda made for the Nazi Party. Directed, produced, written, and edited by the legendary Leni Riefenstahl. The film itself chronicles the Nazi Party Congress Rally in Numberg, Germany in the year 1934, which was attended by over one million people. Riefenstahl is controversial herself, called a simple tool of the Nazis’ by some or a tragic artist that was a victim of circumstance by others.

The film’s presentation and images are what have challenged film historians. Riefenstahl had a true cinematic eye, showcasing the astounding size of the rally and the passion for Adolf Hitler’s words during his speeches. The film was a massive success in Germany and was considered a great success in raising pride in the Nazis. Clearly the film could not make an impact in the United States, but that does mean it was not influential.

Roger Ebert called the film “one of the best documentaries ever made…” and even George Lucas was influenced by Triumph’s cinematography, which is clearly seen in the ending scene in Star Wars. Leni Riefenstahl would continue to make films in Germany and fight to see her visions realized in a tight political system.

The question of author’s intent is very prevalent in the discussion of Triumph of the Will. Detaching its propaganda purposes and accepting its showcase of Adolf Hitler and his control over Germany is key to seeing its achievement. Leni Riefenstahl and her work is a tragic casualty of World War Two. Though her films may never reach beyond their dark cloud, many can see them for their achievements and importance.

2. Blue (Derek Jarman, 1993)

Color is important to cinema. Though the decades of black-and-white films are cherished and still relevant, it was the addition of color to the process that ushered in an entirely new era for the art form. Elaborate color even became a box office draw when Technicolor wowed audiences and created breathtaking viewing experiences.

Cult film legend Derek Jarman had a history of strange film experiences. He was an experimenter and challenged the status quo by using homoerotic imagery to push for queer activism. He created films that fought stereotypes, fought for acceptance, and eventually defying narrative structure entirely. Jarman was also politically vocal, a voice that grew after he was diagnosed with HIV eventually leading to the AIDS virus and his death in 1994.

Although in the wake of his diagnosis, Jarman continued to work until he created his final film Blue. The film consists of single shot of IKB or International Klein Blue which remains static on the screen for 79 minutes. The soundtrack is elaborate with a music score and several performers doing narrations, including Tilda Swinton, Nigel Terry, and Jarman himself.

The cerebral nature of the film and the hypnosis factor of staring deeply into a single color, creates space for the eyes to bend and shape the color. Jarman created the film because the complications of the AIDS virus was causing the detachment of his retinas, causing blindness. He decided to remain a filmmaker by creating a film that forced the audience into an abstraction of pure imagery within the mind.

Blue is Jarman connecting to those who do not understand AIDS and its affects. Towards the end of the film, Jarman’s narration comes a list of names of friends and lovers who died from the virus. The difficulty of this film comes with the abandonment of moving image as important, when a filmmaker himself cannot see.

The audience is forced to watch nothing, when Jarman is striving for everything. No other films have been so simple, but deeply personal and reflective of the creator.

1. The Act of Seeing With One’s Own Eyes (Stan Brakhage, 1971)

A forced and unapologetic confrontation on human mortality, this film is a challenge for any viewer. As one of the most important filmmakers in the history of the moving image, Stan Brakhage is in a league of his own. Over his massive filmography, he experimented with innovative, creative, and unique alternatives to storytelling. He scratched, painted, pressed moth wings, and flowers into film stock to create a style all his own he dubbed poetic lyricism.

By 1971, Brakhage had already established a reputation for evolving what a film could be and image as a window into the psyche. During this period he was creating his Pittsburgh Trilogy. These three films created in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania are Brakhage’s version of “documentaries”.

The Act of Seeing With One’s Own Eyes is the most infamous of the pieces. The film is a document of a Pittsburgh morgue. It is entirely graphic and hides nothing. Brakhage captures an autopsy in all of its details and straightforward deconstruction of a dead human body. Organs are removed, the face is cut open, the skin is peeled back, the brain is revealed and the embalming is shown for what it is.

Brakhage uses no sound for the film, creating an absolutely subjective viewing experience. The gore is presented to the audience without any comment, allowing for people to decide their feelings on watching the human body deconstructed.

The film is said to be a direct confrontation with the audience to accept mortality and show what we as society hide from ourselves. Death is an ever examined complex concept, but Stan Brakhage casted light onto the real thing. The film is a haunting viewing experience, said stick with the audience and create an internal conversation on the human condition. Brakhage wanted to show death, so he illustrated it bluntly and directly.

Author Bio: Joshua Greene is a señor year Electronic Media and Film college student from Delaware. He is an experimental filmmaker and budding film theorist. He is also a working model.