5. Meshes of the Afternoon (Maya Deren and Alexander Hammid, 1943)

This short experimental film by husband and wife filmmaking team Maya Deren and Alexander Hammid creates cyclical visual motifs in an effort to explore the inner landscape of a deteriorating mind.

At the time, Deren herself said that she was inspired to create films in the vein of surrealist pieces like those from Salvador Dali and Bunuel. Meshes of the Afternoon is endlessly fascinating in its depiction of a woman’s descent into madness on one seemingly normal day, and is a masterpiece of avant-garde filmmaking. While the meaning of Meshes is up for the audiences interpretation,

Deren is quoted as explaining that the film “-is concerned with the interior experiences of an individual… rather, it reproduces the way in which the subconscious of an individual will develop, interpret and elaborate an apparently simple and casual incident into a critical emotional experience.”

4. Dog Star Man (Stan Brakhage, 1962)

Stan Brakhage was an American experimental filmmaker whose impressively large body of work spanned decades and influenced countless other directors, writers, and cinematographers along the way. Brakhage experimented with the medium by using multiple techniques including scratching and painting directly onto the film, multiple exposures, and many others to create his singular works.

While none of his works supported traditional narrative, much of what is conveyed in a Brakhage film is conveyed intuitively. Dog Star Man is a collage of pure experimental technique that explores many of Brakhage’s signature themes; mortality, sexuality, mans place in the universe. It’s widely considered to be a masterpiece of the avant-garde and heralded an important new voice in experimental cinema.

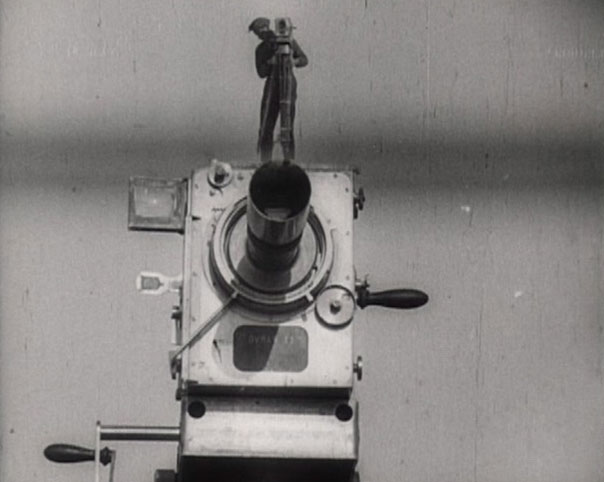

3. Man with a Movie Camera (Dziga Vertov, 1929)

Iconic Russian filmmaker Dziga Vertov changed the course of cinema forever in this groundbreaking non-narrative documentary about the marriage and interaction between citizens and their modern machinery. Vertov belonged to a fraternity of early filmmakers whom coined themselves as kinoks or “kino eyes.” This movement sought to redefine visual language and abolish all non-documentary movies.

Man with a Movie Camera certainly adheres to this scripture as it as zero plot, no actors, no inter-titles, and no sets. The audience is thrust into a dizzying kaleidoscope of soviet montage; employing fast and slow motion, stop motion animation, superimposition, extreme close-ups, Dutch angles, and basically a ton of techniques that modern-day moviegoers take for granted.

This was a game changer. Man with a Movie Camera is not only one of the best non-narrative films of all time, but a timeless classic that helped define the medium.

2. Un Chien Andalou (Luis Bunuel, 1929)

From the collaboration of Luis Bunuel and Salvador Dali, Un Chien Andalou or “An Andalusian Dog” is arguably one of the most important films ever made. Combining Freudian archetypes, dream logic, and incongruous editing we get one of the weirdest and most obscure cinematic experiences of all time.

This is the one that put Bunuel on the map as a startlingly brilliant conjurer of the surreal. The only thing clear in Un Chien Andalou is that we’re dealing with the landscape of the subconscious mind, and Bunuel himself said he did not want the images to have any discernibly logical interpretation. Mission Accomplished.

1. Koyaanisqatsi (Godfrey Reggio, 1982)

In 1982, Koyaanisqatsi made its theatrical debut at the Sante Fe Film Festival. The film was heralded as a one-of-a-kind triumph and went on to surprising financial success in its subsequent release in New York and Los Angeles. Then first time director Godfrey Reggio combines the achingly beautiful cinematography of Ron Frick with a masterful musical score from legendary composer Philip Glass to create a modern masterpiece of non-narrative filmmaking.

Reggio has said that the original concept came out of an interest in bringing what traditionally was the “background” of movies and bringing it to the forefront, making the environment and setting the concentration of the film, not character and plot. As a result, we’re given a perspective never before provided in cinema history.

Over 30 years since its original release, Koyaanisqatsi continues to be imitated, emulated and adored by millions of cinephiles and filmmakers around the world.

Author Bio: Kent Reason is a screenwriting major at Chapman University. His favorite things are coffee, camping and cats.