Film movements are regarded as seminal eras of moviemaking not just for one country in which they are based, but for the entire industry in general and teach numerous people within the industry how to alter the current trend of artistry to initiate another one entirely. When a wave of new and unique films come out, they can forever change the landscape of cinema through experimental techniques, innovative storytelling or masterful craftsmanship.

However though these movements initiate a change in cinema, one has to ask what initiates the movements themselves. Certain films inspire their collective audience to make their own singular visions and can sometimes lead to a tidal wave of artistry and carry a legacy that few films can ever hope to match. With this, they can earn thousands of followers and through inspiring just a few filmmakers within their own country they can ultimately be attributed to shaping the entire world of cinema.

These ten films did just that, they altered their own cinematic scene to ultimately up haul the entire industry. There are of course some movements that cannot trace their origins back to a single film and though they are still important, they will obviously not be on this list. Here I am only looking for movies that can singularly be attributed to the movements they were a part of, and the first of.

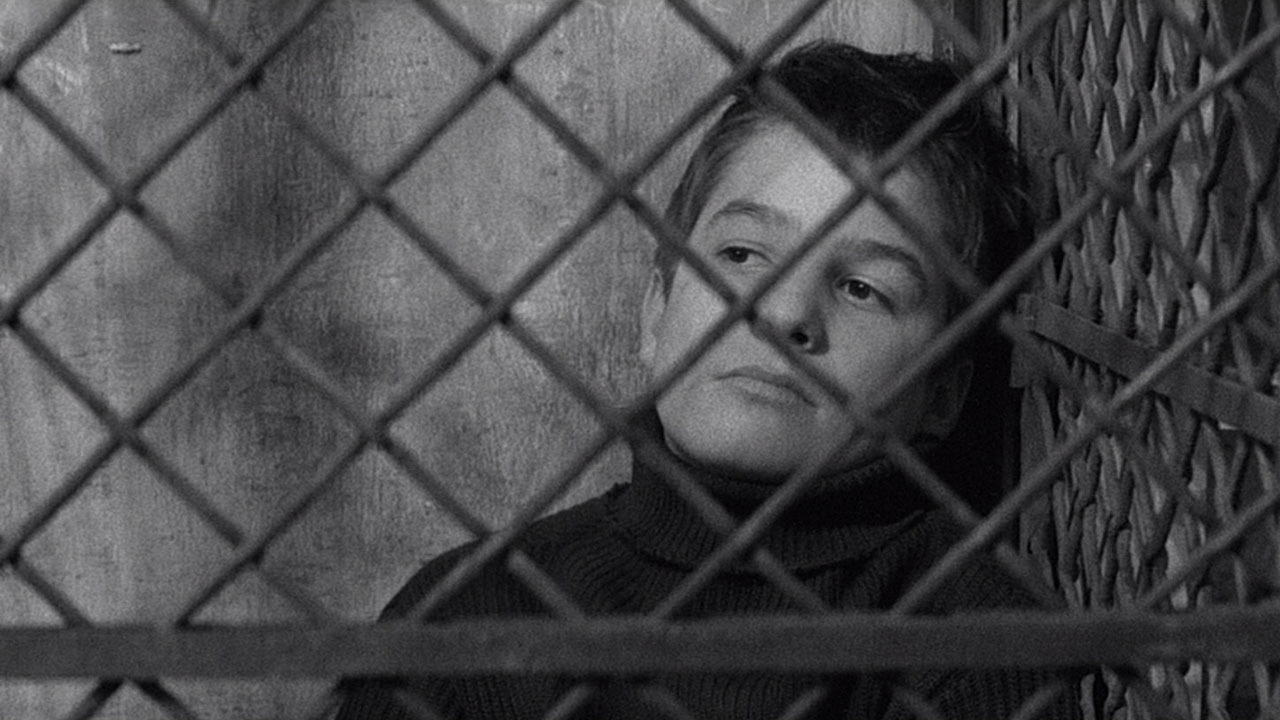

1. The 400 Blows

The origins of the French New Wave are arguably associated with a number of films such as Godard’s Breathless that premiered a year after Francois Truffaut’s coming of age masterpiece.

However for all the technical innovations of Breathless, it was The 400 Blows that centred on what the movement was really about, providing stories that directly applied to the auteurs of the movement, something that was reflective of their lives and experiences. Of course, few things are more personally relevant than a semi-autobiographical coming of age story.

These central ideas are all on display within The 400 Blows and reflect the philosophy of the movement in general. Their films would display the truth rather than pander to viewers, be complex and artistic rather than formed by committee’s and spoon-fed to audiences as well as telling a personal story that spoke directly to their audiences rather than a simple form of escapism.

The 400 Blows covers all of that about as perfectly as any film of the new wave could. It was the story of a misunderstood adolescent that was brutally authentic, compassionate and heart-breaking. It drew attention to French Cinema and was a huge commercial success, when Breathless cemented these concepts a year later (combined with some innovative technical details), the movement was well on the way.

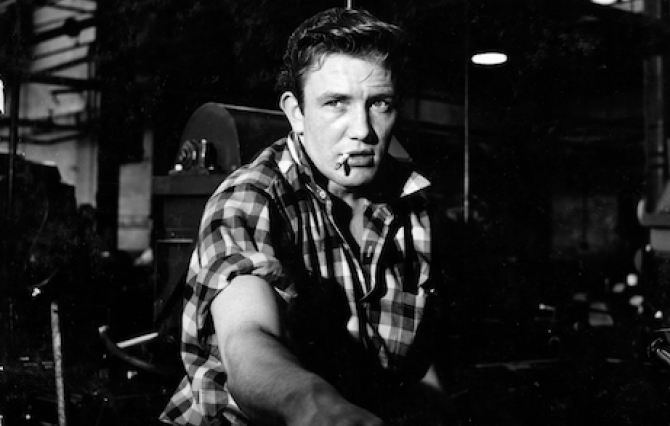

2. Saturday Night and Sunday Morning

British New Wave may be a lesser known wave, but that does not reduce its significance and achievements. Having been focused primarily on high class period pieces, so a drama about a young machinist in a Nottingham factory dealing with the prospect of his secret lover and her unexpected pregnancy was a surprise success, becoming the third most popular film at the British box office in 1960.

Such a revelation ushered in a new age of socially real dramas, or kitchen sink dramas. Films that portrayed the British working class in a more serious and dramatic manner for the first time to mainstream audiences. Saturday Night and Sunday Morning examined the previously unexplored subjects of sex and abortion as the machinist and his married lover consider all of their options before arriving at a hard felt finale.

It coincided with the play writer’s movement known as Angry Young Men and eventually expanded to form a large portion of British cinema at the time as well as enduring to this day in various forms of media from film to TV. They were committed to finding the reality of working class life, challenging the status quo and telling a socially applicable story.

3. Aguirre, Wrath of God

Widely regarded as a masterpiece of the New German Cinema, Werner Herzog’s epic inspired a dozen filmmakers to divert from the current trend of movie making, to make every film that their studios would not allow them to make, ones that contained genuine artistic merit on a massive scale and display breath-taking visuals that would say more about emotion than simplistic dialogue ever could as well as containing strong but subtle social message.

Aguirre ticked all of these boxes with its messages of obsession, as a rogue conquistador journeys into the rainforest in search of Aztec gold. The lingering and powerful images analyse every aspect of the otherwise simplistic tale and elevate it to newfound heights of drama and symbolism.

Despite receiving international critical acclaim, it was poorly received in Germany. A harsher critical reception in its home nation may be why it took other German filmmakers just short of a decade to recognise the importance of the film and how their own styles and techniques could be applied to the same ideologies.

Herzog himself continued to make expressionistic epics of a similar scale, as did Wim Wenders and Rainer Wener Fassbinder, films that focused on a haunting spectacle of stunning beauty and images of unmatched astonishment.

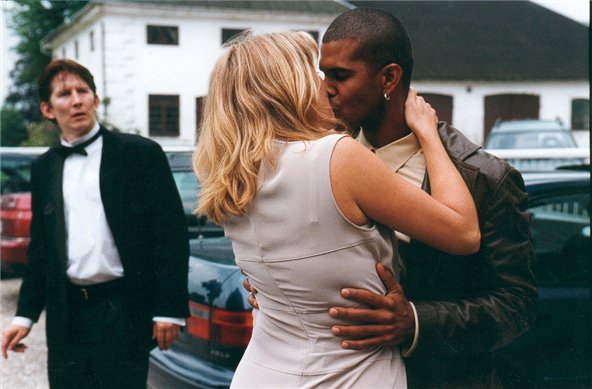

4. Festen (The Celebration)

Few movements can be traced to a singular starting point with as much of a clean cut nature as Dogma 95, an official announcement of minimalism to counter the increasing commercialisation of movies at the time. A manifesto was devised and signed by Lars von Trier and Thomas Vintenberg that laid down the ground rules for the movement such as only shooting with 35mm film, without filters and only using handheld cameras and to exclude added sounds, lights and props as well.

Such theories could well have fallen through and the movement abandoned, what was needed was a physical and well-crafted film to demonstrate how effective these theories listed in the manifesto could be. Festen proved that with the story of a troubled family gathering for their father’s 60th birthday. Having adopted a more documentary like style of filmmaking, the auteurs of Dogma heightened the sense of realism and naturalism within their movies.

Festen was met with critical acclaim, being praised for blending absurdity and tragedy so effectively that it forced audiences to think long and hard about what they had witnessed, examine the consequences and not shy away from the harsher truths that cinema was sometimes reluctant to tell. Festen left audiences eager for more of the experiment that was Dogma 95 and Lars von Trier was ready to continue the movement with The Idiots, and many, many more came after.

5. Boat People

The Hong Kong New Wave was a term used to describe the rise of young filmmakers who used their films to examine domesticity, family and relationships as well as strong political messages. Their techniques were also a significant departure from the mainstream films of their environment of the time as well, relying on the use of location shooting and sync sound recording and explored a grittier, rougher look and feel.

Ann Hui’s 1982 Boat People presented a brutal portrait of life in communist Vietnam, but was widely viewed as an allegory of Hong Kong’s anxieties regarding communist China. It adopted a faster pace and pushed hard for its own identity, unafraid to stand out and create shock waves across the landscape. Its political content earned it unprecedented attention from international critics and was displayed at numerous film festivals.

Most western audiences were used to Hong Kog films being action oriented, while its country of origin were used to films as a staged art form, staying away from realism and politics. As a result of the profound effect, Boat People had the Hong Kong New Wave continues to this day as a huge industry with numerous films that also continue to inspire countless filmmakers across the globe.