6. Rome, Open City

With the destruction of the Second World War still fresh in their memory, Italian moviegoers were ready for a sense of escapism from reality’s troubles. That probably explains why Rome, Open City was met with mixed reviews upon its release. The rest of the world, however, saw it as a bold statement of examining the adjustments to life before the war, highlighting the poverty, oppression, injustice and desperation of everyday life.

The film is set in Nazi occupied Rome and as the title suggests, explores the open city under the regime. Italian Neorealism was associated with capturing a real experience and adding a much needed sense of honesty to a fanciful filled industry. Their stories were bleak and sometimes depressing with a good amount of grit added as well, but they displayed the humanity of their characters and remained true to classical values in order to inspire hope of a more promising future for the citizens of Italy.

Director Roberto Rossellini also utilised a number of technical aspects that were common throughout the wave, such as shooting entirely on location (a necessity as every major film company and studio had been destroyed in the war) and relying on non-professional actors to convey a more truthful story. It was enough to draw the attention of world cinema and with the release of the equally effective Bicycle Thieves in 1948, the movement was cemented.

7. The Cabinet of Dr Caligari

German Expressionism could be one of the earliest definitive film movements, a concept that broke away from mainstream on a large scale and thoroughly pushed the boundaries of what one could accomplish on the big screen. With foreign imports banned during the First World War, it was after the conflict that German filmmakers searched for a distinctive style in which to combine social critique with artistic merit. The culmination of such a need was The Cabinet of Dr Caligari.

Its set design, costumes, lighting, make up were all trademarks of the movement and were solidified with this silent masterpiece. Centring around a doctor that hypnotises a somnambulist in his sleep, it exhibits all of the unique and innovative styles that came to define the genre. It incorporated flashbacks, dream sequences and cinema’s first twist ending.

It also played with concepts of reality and let the directorial designs say more than the actors (not that they could say anything anyway as the films were all silent). It rendered what was previously unseen beautifully observable through exaggerated lighting, shape and expressions.

The movement was sadly short-lived as the rise of Nazism snuffed out the style, one of its biggest contributors Fritz Lang even had to flee to Paris when he was approached to make a propaganda film. But its influence lives on today as it found a new way of handling art and honesty in a way that few have replicated since.

8. Rome ‘78

No Wave was a movement that went beyond just the parameters of cinema as it also extended to the music and art industry. Having been initiated by a group of young auteurs in the lower East side of New York, they were limited with their resources but unbounded in creativity. It used a guerrilla style of filmmaking that was stripped down and put a greater focus on mood and texture above all else, heralding significant success for both the underground film scene and independent cinema as a whole.

James Nares opened the style up for imitators and followers with his Rome ’78. It was his only venture into a feature length, plot driven film but proved to be highly successful critically and stands as a staple for the movement. Despite containing a large cast and period costumes, it was not intended as a serious project, or an undertaking that would ever be respectively viewed. The actors would interpolate uncomfortable laughter into scenes and deliver what were apparently improvised lines with over-the-top bravado.

Yet somehow the project came together to form an utterly unique style of filmmaking that inspired numerous other directors to bring their own ideas to the screen, regardless of their limitations and disadvantages. The No Wave movement also emphasised a complete departure from the mainstream, to tell specific stories that could resonate with a small group of people and fly over the majority, pushing transgressive films to new heights.

9. The Hour of the Furnaces

Once described as the paradigm of revolutionary and activist cinema, the documentary feature directed by Octavio Getino and Fernando Solanas was essential to the political film movement known as Third Cinema.

If First Cinema is for commercial gain and Second Cinema describes artistic movies, Third Cinema was comprehended as a method of revolution. Having originated in Latin America, its aims were to illuminate the oppressed of the political situation that kept them inhibited through a severely censored setting.

The Hour of the Furnaces was the documentary that initiated it, constructing a critical analysis of the political situation within Latin America at the time as each dimension of oppression is examined such as history, economy, sociology, geography, culture, religion and ideology from their fortitudes to their consequences.

The film was produced using the strongest form of guerrilla filmmaking in film history, to such an extent that each individual screening was a risk to the makers and viewers of the film. The simple decision to watch the film became a political statement in itself.

The techniques the film utilised ranged from direct cinema to collages and from animated effects to psychedelic properties. It proved that amid revolutions and uprisings, cinema could be used as a weapon to accompany that arsenal, sometimes the most effective one of all.

There are a number of Latin America countries with movements associated with revolution such as Brazil, Cuba and Argentina and they all fall under the category of Third Cinema and it has also extended to other continents with problems of colonialism including Africa, Asia and Europe.

10. Bonnie and Clyde

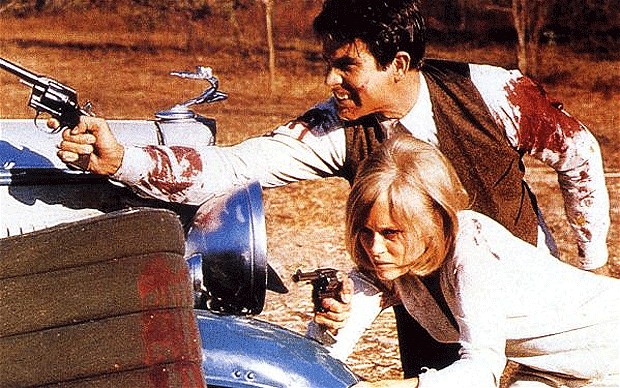

The New Hollywood wave gave prominence to many legendary filmmakers such as Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola and Sidney Lumet, but perhaps the most significant film of the era came in the form of Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde. Through a mix of graphic violence, sex, action, tragedy and comedy, Bonnie and Clyde resonated strongly with the youthful audiences and the fact that its titular characters were star crossed, disaffected young lovers only made it more appealing.

Throughout the film’s production and in the build up to its release, the studio put pressure on Penn to alter the films content, viewing it as a departure from what was traditionally critically and commercially successful. Not only was it a huge box office success, but it was also nominated for a number of Academy Awards. Bonnie and Clyde manages to be ruthlessly cruel yet also utterly sympathetic to its central characters, and uses its violence to contrast its own artistic merit.

By avoiding any sense of condemnation, Bonnie and Clyde managed to remain morally ambiguous and did not draw lines between what the filmmakers thought or studio thought of the issues in the film, they allowed the audience to make their own decisions concerning how they viewed these characters, whether the celebrate or denounce them.

Understanding the impact of this film is important in understanding the impact of the entire New Hollywood Movement as its success heralded an age in which studios would now relinquish their creative control to the directors of the films, such masterpieces as The Godfather, Dog Day Afternoon and Taxi Driver were to follow.

Author Bio: Joshua Price considers himself more of a fan that happens to write near insane ramblings on movies and directors like Scorsese, Spielberg, Fellini, Kubrick and Lumet rather than an actual critic and other insane ramblings can be found at criticalfilmsuk.blogspot.co.uk.