Do you not know that King Kong the first was just three foot six inches tall? He only came up to Faye Wray’s belly button! If god could do the tricks that we can do, he’d be a happy man!

Eli Cross, film director — The Stunt Man (1980)

Historically, every decade has a feeling to it and film is no different. Each decade brings with it a certain style, certain flavor, as film directors and their careers, along with the stories they are passionate about, rise and fall with the wind and whose own proclivities tend toward group think and playing it safe on one hand (pretty common) and utter originality on the other (very rare.)

Directors can spend their entire career in one genre only to shock you with a picture out of nowhere unlike anything they’ve ever done. Usually, this is a long-gestating vanity project rewarded to the director by a studio for breaking box-office records the year before. Money is given. The director directs. The film is released and the audience is left wondering.

Modern audiences — especially the mumblecore set — may not care for the older styles of filmmaking. The farther back you go, the acting and script tends to get more stylized, more theatrical, less visual. There are many exceptions, of course, but mainstream feature films tend to play it safe. No one goes to the movie to experience real life… they go to the movies to be entertained. As a result, films have a job to perform, and very good films do this job very well to a degree that you hardly notice it.

Making films is highly technical, and script writing is the most technical of the lot. There is a reason why scriptwriters are placed in the title credits just before the director. Films do not sound like real speech (nor should they ever). They are truncated, choppy, loaded with subtext. It takes real skill to write this way. Newer films have a more easy, colloquial way about them but they still all follow the same rules. When a movie doesn’t play well, look at the dialog first.

A masterpiece such as West Side Story that wore its theatricality on its sleeve would be laughed at were it to premiere today. Verisimilitude was not a goal at that time, and to shoot on location was an expensive rarity.

West Side Story’s odd mix of ballet, ghetto, and operatic form was highly unusual but clearly metaphorical, maybe even metaphysical. I was 8 when I first saw it and could never understand how Tony and Maria, singing their guts out on the balcony, couldn’t be heard by Mama and Papa in the very next room. The thunderous music by Bernstein and ecstatic, jazzy, hip-thrust dancing by Robbins and loud proclamations of “COOL” and “POW” were surely loud enough to draw the attention of the authorities! My naiveté was cute.

This article starts a new series for me — a retrospective of lost or forgotten gems from the last 100 years. I will be going by decade, not always consecutively, discussing 15 films in detail, with added remarks about each director and their career. Clearly the list is personal but heavily researched and not without some thought.

In most instances, you will not see generally well-known titles with few exceptions. In my life, I’ve seen over 2,500 films. Some of them were very good. Many are now forgotten by audiences too busy with the current decade much less from decades past — those films are remembered only by the most devout film student or cineastes. Time to resurrect the some of the forgotten ones for future generations so that all may love on these mostly idiosyncratic perfections.

1. The Stunt Man (1980)

In films about filmmakers and the making of films, Richard Rush’s The Stunt Man is king amongst its kind. It relaunched Peter O’Toole’s acting career — which had been derailed in the 70s — and almost singlehandedly drove a marked resurgence in American independent cinema. Not bad for a troubled production and film that languished on the studio shelf for almost two years before being shown to a real audience.

The movie follows a man on the run from the authorities (Cameron, played by Steve Railsback, affectionately renamed “Lucky”) who stumbles across a film crew and ruins a critical shot that accidentally kills the picture’s stunt man.

The film now needs a replacement and quickly. The film’s bombastic director (Eli, played by Peter O’Toole) and the wary fugitive agree to a Faustian bargain that will benefit them both — one has a place to hide by becoming the new stunt man and the other can finish his film on schedule free from studio threats and the very same authorities that plague “Lucky.”

The movie is loud, brassy, brash, and an odd combination of fantasy and reality, pathos, black comedy, social satire, action adventure, laced with complicated, multi-layered structure that, for 1980, was very rare. It’s part of the films real-life mythology that studio heads just didn’t get it and couldn’t figure out how to market it so they did nothing and it languished on the shelf for two years. Slowly, it crept out of the closet and was shown at several specialized film festivals in the Northwest where the crowd was more astute and received it with resounding affirmation, allowing for a wider release.

Eli Cross, the fictional film’s director, describes “Lucky,” the new name for the new identity as a “…a stuntman… who is an actor… who is a character in a movie… who is an enemy soldier,” who in real life is also “a fugitive who plays an American flyer posing as a German soldier… who is a fugitive.” (Last quote taken from an Australian DVD box.)

The movie has great fun with body doubles, switched identities, masquerades, charades, and lots of industry talk about film and filmmaking — all of it lorded over by a film director who is both crazy and brilliant, manipulative and maybe even evil, who is shooting a WWI film in the middle of San Diego at the Hotel del Coronado.

One never knows, often, if one is in a film set or real life, because little of makes any real sense — which is part of the point! The cinematography by Mario Tosi frames the action in a hazy, bright color palate with lots of light flare to accentuate the dream aspects of the film.

This is a highly unusual film and deserves to be reborn in our collective imaginations.

2. S.O.B. (1981)

Nothing says “Hollywood” more than taking a subject it doesn’t really like in the first place (industry introspection) and doing it again with a twist, and this time directed by Blake Edwards, one of the greatest modern directors of physical or set-piece comedy who ever lived.

Semi-autobiographical, it follows the exploits of a film director whose G-rated film bombs and he tries to salvage the picture by turning it into an R-rated picture instead — think Snow White as directed by Bob Fosse. The film is partially based on Blake Edwards’ real-life challenges with the making of his Darling Lili that starred Julie Andrews. S.O.B. — here meaning “Standard Operating Bullshit” — again stars Julie Andrews (Edwards’ wife in real life) and many of Edwards’ regulars.

In a sense, Julie Andrews plays an actress portraying herself in a film that satirizes her squeaky-clean image by making a film that satirizes her squeaky clean image and efforts to prove otherwise in prior films her husband made staring herself! The only thing missing is Blake Edwards playing himself as the director.

No other film has this much fun except 1979’s All That Jazz, Bob Fosse’s scathing film autobiography about his life as choreographer and film director. Clearly, S.O.B. was inspired by Fosse’s film in several ways. S.O.B. is also known for Julie Andrews’ one and only nude scene (breasts.) It was also William Holden’s last film — he would die in an accident at home shortly after completion.

S.O.B. is a scathing indictment of the movie industry. Many actors portray thinly disguised versions of real-life counterparts. The film is loaded with inside jokes, references, and re-enactments of actual events from Hollywood’s sordid past and none of it is particularly complimentary. You can even say the film is somewhat mean-spirited, which may have contributed to its lack of box office success. Satirical comedy, even when skewering, should still have a heart.

Blake Edwards, by this time, was so famous and successful, only he and a few others would be able to make a film like this and get away with it. Blake Edwards was, of course, Hollywood royalty and directed over 70 pictures in a career spanning over 50 years, who produced, acted, wrote, and directed. His stepfather started in silent films. S.O.B. was the next picture after 10, one of the most successful pictures of 1979 and launched Dudley Moore’s middling career into the stratosphere and Bo Derek onto the walls of every teenager in America. Latitude was given.

Still, it is hard to describe the level and length this film went to skewer the very industry that made Blake Edwards a very rich man and allowed him to live a life of exceptional comfort and style until his death in 2010. There is no disputing his talent or career contribution — he made billions for his investors over time.

There is no question Hollywood is part legend, part myth, existing in a netherworld of imagination and power. It is truly a city of Dr. Jeckylls and Mr. Hydes and Faustian bargains and the rules of the game are changeable and open to criticism or satire within reason.

And nothing says “Hollywood” more than redemption. The very next year after burning the industry down he delivers one of the industry’s mega-successes of 1982 — Victor/Victoria — one of the greatest musicals ever that was bathed in Oscar® and award glory and also allowed Mr. Edwards to continue working unimpeded. In Hollywood, nothing says “forgiveness” more than boffo box office and one is never too far away from keys to a Rolls Royce or a foothold on Tin Pan Alley.

Together — S.O.B. and The Stunt Man — are part of a long line of films about filmmakers and filmmaking that shows mixed results over time. The movie-going public typically does not reward the genre with box-office except on rare occasions.

Here are just some of the greats (in no particular order and in no way a complete list): Day for Night (1973), Tropic Thunder (2008), 81/2 (1963), Singing in the Rain (1952), Argo (2012), The Player (1992), Mulholland Dr. (2001), Peeping Tom (1960), Adaptation (20012), Boogie Nights (1997), Barton Fink (1991), Sunset Blvd. (1950), The Bad and the Beautiful (1952), Stardust Memories (1980), Swimming with Sharks (1994), Day of the Locust (1975), Tristram Shandy: A Cock and Bull Story (2005), and All That Jazz (1979).

3. Cutter’s Way (1981)

Formerly known as Cutter and Bone and later retitled and rereleased again as an art house film, this is a marvelous character study of a Viet Nam vet, his wife, and his best friend as they become obsessed with tracking down a killer after they witnessed a murder. At the time, it was a highly regarded film by critics and audiences.

This film was very typical of the kind of film Hollywood made in the 70s and part of the 80s and is a type and style I greatly admire — small- to medium-sized budget films driven by a good story and great actors. Even if at times studio chiefs were mystified about the marketability of films like this, they gave it a shot because they were not all that expensive to produce. For all the behind-the-door wrangling and controversy, Cutter’s Way eventually turned a nice profit and everyone involved can look back on this picture proudly.

The film had the added benefit of being photographed by the exceptional Jordan Cronenweth, who cemented his genius status with films like this one, Altered States (1980), State of Grace (1990), several concert films, and, of course, the great Blade Runner (1982).

Cutter’s Way does find itself on cable TV from time to time though with little fanfare. If you see it posted, please give this small, character-driven film your attention.

4. Prince of the City (1981)

As Marty Scorsese will forever be associated with the Mafia, Sidney Lumet is certainly the other side of the coin.

Revered when it premiered in 1981, it typified Sidney Lumet gritty, neo-realistic obsession with those charged with protecting — and flouting — our laws. In almost a dozen films about law or law officers — 12 Angry Men (1957), The Anderson Tapes (1971), Serpico (1973), Dog Day Afternoon (1975), The Verdict (1982), Power (1986), Q&A (1990), Night Falls on Manhattan (1996), and Find Me Guilty (2006) — he explored every facet of the gray area between integrity, justice, and the evil men do — often all at the same time. In Lumet’s world, the hero is resigned to a loner’s life who sacrifices himself for the common good. Redemption usually comes at the expense of life or long reward. The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few.

Lumet’s shooting style is brisk. I’m not sure he was ever over budget or finished beyond the shooting schedule. Honing his craft from years of live TV theatrical directing, he develops the story and rehearses his actors so that filming is a mere byproduct, not a gut-wrenching experience. Rarely are multiple takes required.

Every budding filmmaker would do well to emulate Lumet — his string of hits is a long one. Aside from the crime dramas mentioned earlier, The Hill (1965), Murder on the Orient Express (1974), Network (1976), Equus (1977), Deathtrap (1982) and Running on Empty (1988) are all equally exceptional films.

For most of his career, except for one exception, he concentrated on character-driven stories. His one exception being the much maligned The Wiz (1978) — a big special-effects movie based on the hit Broadway musical and staring Michael Jackson. It’s an exceptional misfire and a slo-mo train wreck that never fails to hold your attention.

It is impossible to take your eyes away from it for all the wrong reasons. It skillfully combines actual NYC locations into the warp and woof of the film’s OZ fantasy storyline that eventually culminates at the pre-911 World Trade Center. Odd film. Odd choice.

Three years later he rebounds by getting back to his roots with Prince of the City — one of his best. Now, almost two generations removed, it’s time to revisit this great film.

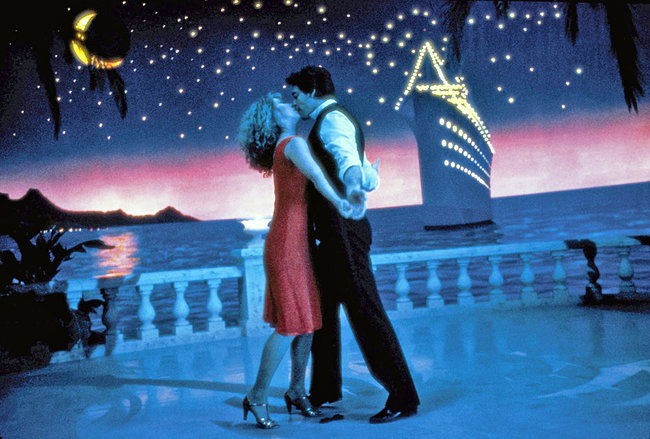

5. One From the Heart (1982)

Question: how do you follow up Apocalypse Now?

Answer: with a semi-experimental, semi-surrealist, impressionistic musical about a couple on the verge of a bad breakup that wound up costing Francis Ford Coppola $25 million dollars. It became one of the biggest flops in motion picture history (and the biggest flop in Coppola’s career) and quickly forgotten by all except the Coppola himself who spent the next decade or more as director-for-hire to repay his debt for this odd, experimental miscalculation.

Which is all the more reason that this long-forgotten, infamous film deserves another shot. Like The Stunt Man, One From the Heart’s unusual concept, musical storyline, and highly-stylized, deliberately fake production design was ahead of its time (or far too late, depending on how you look at it.)

Not like anything ever produced in the modern era, the film harkened back to Busby Berkeley and MGM musicals, especially the likes of An American in Paris (1951), Singing in the Rain (1952), or Kiss Me Kate (1953) — whose very artificiality is a leitmotif and almost a character unto itself.

Audiences were simply not ready for narrative films looking or sounding like this — especially this effort from the director of The Godfather Parts I & II — verismo masterpieces about one of the most chillingly evil character ever put in film and as perfect as two films could ever hope to be. For all Coppola’s genius, this one had people scratching their heads.

Musicals were long considered a dead genre, especially in the 70s with only a few exceptions — Fiddler on the Roof (1971), Cabaret (1972) and Grease (1978). And even though films like Fame (1980), The Blues Brothers (1980), and Victor/Victoria (1982) in the early 80s did very well, most of that decade was a string of expensive failures too. You have to give Hollywood cred for continuously trying. Hollywood is one industry that never says die. Genres fail some decades and score millions or billions of dollars the next.

Coppola directed most of the picture via closed-circuit-TV from a remote RV and stage directions would come via loudspeaker even though it was filmed entirely within a sound stage with a meticulous recreation of Las Vegas in miniature.

It was filmed in an almost collaborative, workshop style, rather than in the usual, structured manner, with shooting, editing, and revising coming almost concurrently. On top of making a new kind of art form, he was experimenting with methodology, questioning entrenched values, always thinking and experimenting, always pedagogical.

30 years later, what was a sacrilege then is commonplace now. Almost all directors use some type of video playback system. With the always-improving CGI, most directors shoot on set and not on location.

Directors now extensively collaborate with a variety of sources and experiment with a variety of techniques and technology — sometimes even camera phones. Most importantly, modern audiences are now used to multi-layered, oddball films where almost anything goes and eagerly accept a variety of techniques or structures from creative directors looking to tell a story differently.

Critics savaged One From the Heart. All Coppola was trying to do was act the artist and create and direct from the heart. His mistake was his vision exceeded his budget as it had always done. Few would deny any major director work on smaller films, but do it at a much smaller cost to match. Hugely expensive, it made only $900,000 back.

In many ways, Coppola would never recover. He still made very competent and entertaining films on average about one per year or so — Rumblefish (1983), The Outsiders (1983), Tucker: The Man and his Dream (1988), Dracula (1992), and Tetro (2009) stand out — but gone was his lust for life.

One From the Heart should easily find a new audience that can fully appreciate its quirky way and haunting music and luscious cinematography. If One From the Heart were made now, it would be hailed as a masterpiece in these modern, accessible, anything-goes times.