Existentialism can be defined by French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre’s phrase existence precedes essence. It means that, for existentialism, a man is not his own end, since human existence only happens when it is designed beyond itself. According to the philosophy of existentialism, a man exists before being, and must give his life sense, since he is only what he makes of himself.

Existentialism historically flirts with the arts, literature and cinema, Jean-Paul Sartre, dramatist, existentialist philosopher and writer, certainly believed that. Existentialism also has its history linked to protests and reactions against the status quo in the policies of many countries, against fascism and dictatorship, in favor of freedom and free speech.

In international cinema, many directors portrayed themes and aspects connected with the philosophy of existentialism, such as Michelangelo Antonioni, Jim Jarmusch, Jean-Luc Godard, Jean Eustache, Alain Resnais, Hiroshi Teshigahara, Andrei Tarkovsky, Yoshishige Yoshida and many others.

Existential cinema discusses the darkest existential subjects such as anxiety, absurdity, loneliness, , death, and emptiness. But it also deals with life lived in subjectivity, portraying the struggle of everyday life in an existential perspective when people find themselves against the world, under circumstances and responsibilities that are the results their own choices.

This list brings together a selection of directors who flirted with existentialist philosophy. Of course, the list deserves to be much longer, but its intent is to illustrate in a wide range how existentialism has been employed by various directors of several nationalities. If you are looking for more great existential films, you can check out another descent list about existential cinema on TOC.

1. Tokyo Story (Yasujiro Ozu, 1953)

Few movies have managed to deal with universal themes like family life, loss, aging and loneliness in a sincerely and powerful way like this masterpiece of Japanese cinema. Tokyo Story (1953) portrays common situations of anyone’s life, such as parents who fear that their children are not becoming adults prepared for the world or the natural remoteness an adult feels towards family. The plot shows an elderly couple that decides to leave their quiet town to visit their children in Tokyo.

Director Yasujiro Ozu shows us the respectful way, but also the cold way, that children are related to their parents. It is not just indifference, they do not seem to dedicate much time to their parents. At a certain point in the narrative, one of their daughters uses a feigned delicacy to take a severe attitude, making the old couple feel as though they are genuine hindrances. Interestingly, the only person who seems to care for them is one of their daughters-in-law.

The film unfolds unhurriedly, with a relatively slow pace, but one that is never overly tiring, and in a certain way melancholic as the development of the narrative reveals all the loneliness of human beings and all the selfishness of man. In addition, at the end of the movie, Setsuko Hara says with a sad smile: “Isn’t life disappointing?” This moment imbues the movie with serenity, balance and gentle resignation. With the impact of emotion in its purest form, deprived of sentimentality, the viewer experiences a feeling of fullness and the psychological comfort of a discreet euphoria, and a sentiment of an existential void when the movie ends.

2. Hiroshima Mon Amour (Alain Resnais, 1959)

Hiroshima Mon Amour (1953), the first full-length film by the French director Alain Resnais, previously known for his fabulous and dense documentaries, this film is an adaptation of a manuscript by writer Marguerite Duras, whose work flirted with existentialism. The combination of Duras’ text with the mixture of image and sound by Resnais transform the movie into something modern.

The bodies of two lovers entwined in bed acquire multiple textures of sand and ashes as we hear them talk in voice over. The woman is a French actress passing through Hiroshima, hometown of the Japanese architect who she had met the day before. Theywonder if she had seen Hiroshima, whether she would have even been able to have this kind of experience after a bomb killed two hundred thousand people in nine seconds.

This striking opening scene is the thread of a film that lies between documentary and fiction, cinema and literature, existence and memory. It discusses what human existence is made of. The precarious unity of the self, as stated by Resnais, depends mainly on theways, always singular, we remember, forget, love and die.

3. Vivre Sa Vie (Jean Luc-Godard, 1962)

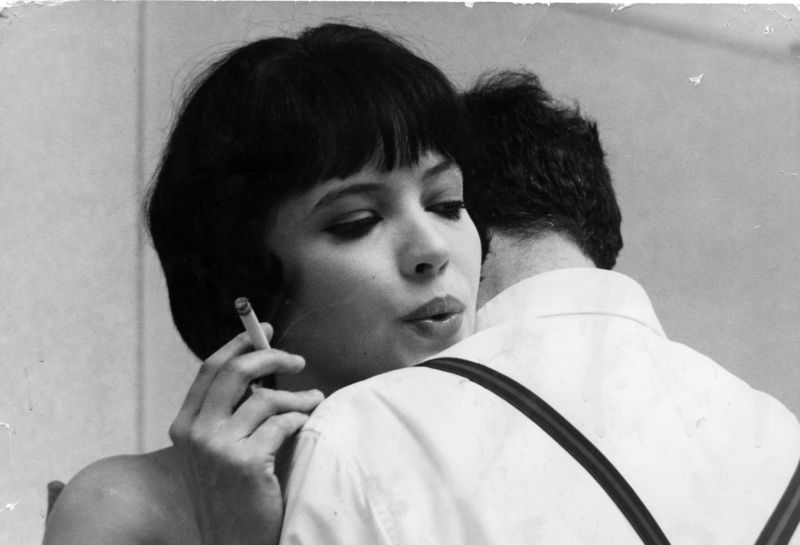

In Vivre As Vie (1962) the camera acts as a detective. Nana (Anna Karina) is presented to us in the distance, and sometimes we even lose the sight of her. We do not have an intimacy with her. We are observers like the men who surround her, curious as to the price of the night. Godard places us in the position of anyone.

Nana’s sadness is printed on the film with teary eyes. There are no secrets. Her body and soul are observable to whom it may concern, Nana’s tears are highlighted by strong makeup, she is not well, but she want to pay the price. Or rather, she desperately wishes for someone to find her and tell her how much life is worth.

“I think we’re always responsible for our actions. We’re free. I raise my hand – I’m responsible. I turn my head to the right – I’m responsible. I’m unhappy – I’m responsible. I smoke a cigarette – I’m responsible. I shut my eyes – I’m responsible. I forget that I’m responsible, but I am.” So then, Nana denies the role of victim and takes all the blame that is still to come, now that she is a prostitute. There is no one better than a prostitute to talk about guilt. In Vivre Sa Vie Godard uses existentialism to explain the pain that everyone faces at some point in their lives.

In the director’s vision, Nana pays the price for living. The responsibilities described by the protagonist preclude a fulfilled life, the search for happiness or the escape from sadness requires too much time, almost her entire life. Nana, seems to feel better when she understands the message. This makes her understand herself better and near the end of the film she is no longer the same, and neither are we.

The experience of the viewer is like that of Nana: there is no place to run. Any of Godard’s films are a torrent of visual and philosophical information and Vivre Sa Vie is nodifferent. When the movie ends, we became thoughtful: what is it to live a life?

4. 8 ½ (Federico Fellini, 1963)

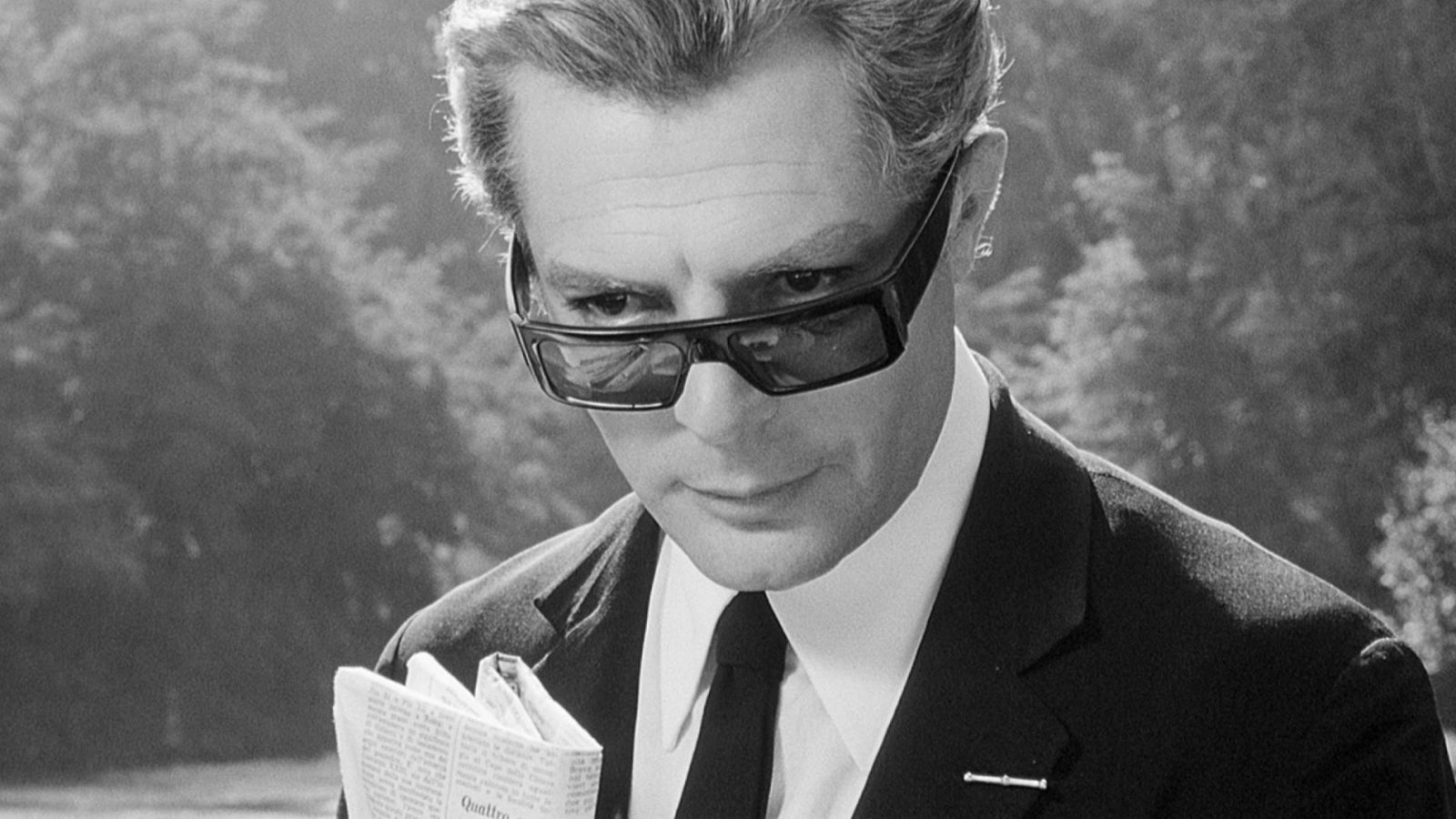

Guido Anselmi, a renowned Italian director, has a crisis while preparing his new movie. Looking for a rest he goes to a spa resort in order to collect his ideas. As the new film is already in an advanced stage of production, a huge team accompanies him, including technicians, actors, producers with mobster airs and even a film critic.

All of them continually ask for something he cannot give: a direction, a meaning that could unify and harmonize all the elements of the film, the chaos of which is analogous to the personal life of the director. Oppressed by the inability to find such a sense, Guido almost gives up everything, until, in a moment of inspiration, he challenges the classical concept of the Beautiful in art and manages to produce a revolutionary art, supported by a new understanding of the origin of art and the artist’s task

5. Pale Flower (Masahiro Shinoda, 1964)

Masahiro Shinoda, in his first contact with cinema, was working as assistant director in films directed by Yasujiro Ozu. He also had a rich knowledge of Japanese culture. Outranked by the filmmakers of his time by always choosing to portray the past, in several interviews he emphasized the power of the past over the present in fiction, especially when adapting scripts from the writer Shuji Terayama or even literary works.

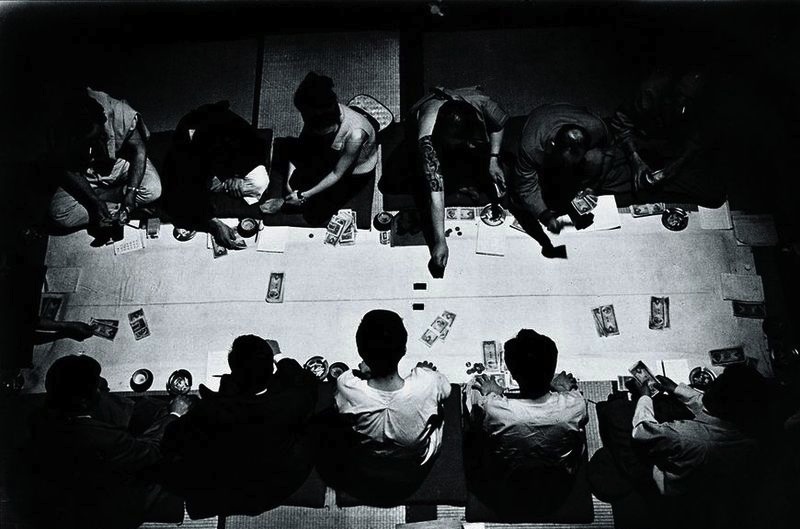

Pale Flower (1964) portrays the life of a yakuza who recently got out of prison and begins to play a card game called hanafuda. As the days pass, he finds himself more and more immersed in this dangerous world. With the American film noir atmosphere and stunning expressionist photography in monochrome Cinemascope, Shinoda creates a complete film experience.

Even the card game scenes, with a deck that has twelve suits all named after flowers, have an intensity that is agonizing yet intriguing. There is also a surreal/op-art dream sequence that adds to the stylized atmosphere of the film as does the avant garde soundtrack by Toru Takemitsu. Pale Flower is an unforgettable picture, permeated with a nihilistic philosophy and an impeccable aesthetic to create a masterfully involving noirish parable.

6. Blow-up (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1966)

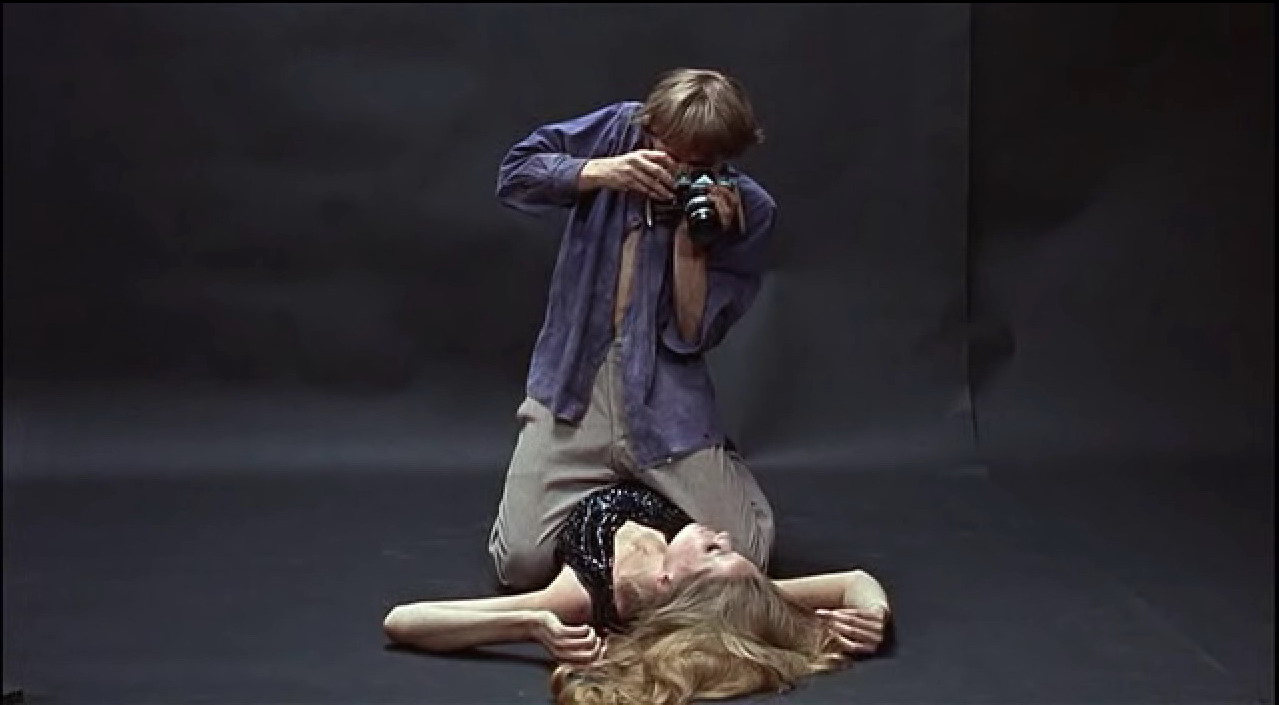

In a swinging London of the second half of the 1960s, Thomas leads a double life: he is a rich and famous fashion photographer, with his studio replete with beautiful models and other celebrities of the fashion world, and at the same time Thomas is an anguished artist, looking for images that emerge from a true reality, different from those that he usually produces.

When, after successive enlargements of a photograph taken in a park, he finally stumbles upon one of those photographs – a mysterious assassination. However, Thomas finds himself unable to prove their objectivity. Is there a clear boundary between truth and illusion, reality and representation, the objective world and the subjective? This question asked byThomas is provocative forthe viewers of Antonioni’s film and is probably the key issue of the contemporary philosophy.

7. Memories of Underdevelopment (Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, 1968)

One of the most notable films of the Cuban cinema is Memories of Underdevelopment, which was clearly inspired by the French avant-garde cinema, especially the Nouvelle Vague.

The narrative is non-linear, the images follow one after another in unpredictable developments, fragments of memory and present time merge without prior notice, with nothing todelimit the space of each. The camera exposes everything unashamedly, showing to the viewers that this movie is not a representation of a unanimous truth.

Moreover, opposed to the logic of classical cinema, the viewer is bombarded with unusual images that are seemingly senseless. But as the movie progresses these images erupt unexpectedly, breaking the plot. As in the French avant-garde style, the film develops from a long monologue in which the protagonist expounds about the condition of his life in the midst of a country in transformation. The speeches of the protagonist are ambiguous and the meaning is not immediately apprehended. These speeches focus on dilemmas of human existence above and beyond the political conditions of the contemporary world.

The main character wanders around the world, free of moral ties and wholly given over to the unpredictable, as a wandering Belmondo. Just as Nouvelle Vague was a child of existentialism, Memories of Underdevelopment also embodies to some extent the principles of this extremely influential philosophical movement of the 60s.