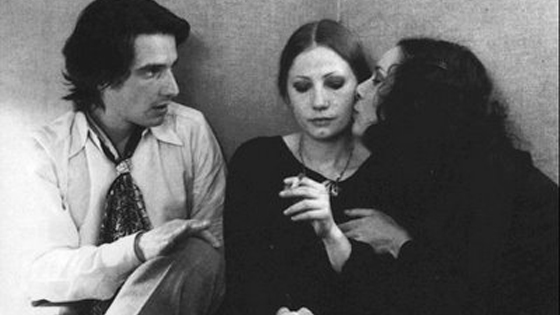

8. The Mother and the Whore (Jean Eustache, 1973)

Over the course of the narrative of the film The Mother and the Whore there are some suicidal characters. Some of these are women and are mentioned by the protagonist, a man, played by Jean-Pierre Léaud, who would have had relationships with them.

Léaud notably refines his interpretative style, extracted from his experience in the films of François Truffaut and Jean Luc-Godard. The film develops into a central triangle: Alexander / Léaud, a character who seems to be imported from the Sartre’s novel, Nausea) andMarie, who lives with Alexander and Veronika, the prostitute that Léaud begins to hang out together

The Mother and the Whore was a film shot by someone on the verge of suicide. It is a film of a motherless kid. That is the curse of of Jean Eustache, who buried his film in oblivion and committed suicide in the end of 1981.

In this film, we can not miss the father of existentialism, Jean-Paul Sartre. , The characters in a café mention the presence of Sartre at a nearby table. Of course Eustache don’t showSartre, just what the characters say about Sartre is: an existentialist wolf parading his Maoism in French cafés while exhaling his drunkenness.

Such references overflow from the film, from literature and cinema to music and various classics. But especially the voice of Edith Piaf, which has a proper tribute in a particular scene. Marie, the character played by Bernadette Lafont, is lying in a bed while her man and his mistress leave the room. A she starts to listen to Les Amants de Paris she covers her eyes with her hands. Tthe voice of Piaf pervades the long fixed shoo and the film becomes the song and the song becomes the central character of the scene.

But the greatest moment of the film, and the most disturbing fixed shot, is the monologue by Françoise Lebrun, the whore-mother,. She openly speaks of her deepest desires to thecamera. She speaks while the camera wanders blankly, her half-closed eyes open from time to timeto spy on the viewer’s behavior.

Perhaps this discrete look toward the viewer is the explanation for a film like The Mother and the Whore: who is the observer on the other side of the screen?

9. Stalker (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1979)

Next to a nameless and dark city, there is a place named as the zone whose peculiar and dreary nature is permeated by an unknown origin.

Surrounded by an enigmatic and decadent atmosphere — abundant vegetation, rusty tanks and ruins everywhere — the zone is a forbidden territory lethal to whomever enters. Only a few people know the secrets of the zone and cross it unharmed. These people are called Stalkers. The Stalkers, in exchange for money, illegally lead people to the interior of the zone where they are motivated to achieve the room, a place that has the power to fulfill the wishes of those who visit.

One of these Stalkers guides two men, a writer and a scientist, in their quest to get to the room. Stalker (1979) is a film about the ways people have to choose to go through life and allows us to consider what is the specificity and nature of a philosophical discourse.

10. Stranger Than Paradise (Jim Jarmusch, 1984)

Stranger Than Paradise (1984) is divided into three acts. In the first part, when the Hungarian Bela Molnar, who lives in New York, is visited by Eve, a cousin who came to the US to start new life, despite the strangeness of the American way of life. In the second part of the film, a year later, Bela and his best friend, Eddie, are caught trying to cheat in a poker game. They steal a car and run away.

In the last part of the film, the three venture towards sunny Florida, with unpredictable consequences. This is a reversed road movie, where bored characters are not transformed by their experiences. Instead, these characters are carried away by circumstances in a different way. The film translates its atmosphere and the attitudes of its characters in a minimalist style, based on one of the most important works of French existentialism, “The Stranger,” by Albert Camus.

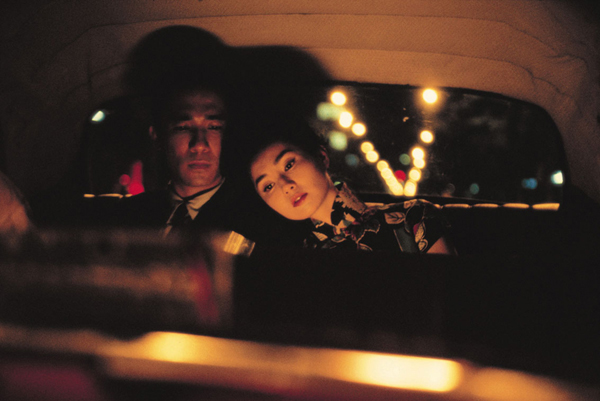

11. In the Mood for Love (Wong Kar-Wai, 2000)

Su Li-zhen and Chow Mo-wan are neighbors in 60’s Hong Kong who are inevitably drawn together as they become convinced that their spouses are having an affair with one another.

If a different director had shot this movie, In the Mood for Love would have been an existential period piece about loneliness and forbidden love, but in Wong Kar Wai’s masterful hands, sexual tension is drawn out with intensity and delicacy. The highly stylized cinematography serves as a visual contrast for the inner universe of the characters and the world around them that is meticulously structured in the film in a subtle atmosphere.

12. Yiyi: A One and a Two (Edward Yang, 2000)

A series of events involving Jian’s family results in a succession of episodes, initially isolated, but which eventually come gradually together in a tangle of connections whose common bond is the approach of existential questions about love, violence, illness, aging and death.

In this unsophisticated film, director Edward Yang strikes us in how he presents these existential issues Yiyi: A One and a Two invests in the art of seeing, and its possibility of cure and the continuous transformation in our relations with existence, by formulating a refreshing and stimulating pedagogy of seeing the truth behind the monotony of everyday life.

13. Dogville (Lars von Trier, 2003)

We are in the thirties. Running away from mysterious gangsters, Grace comes to Dogville ,an American town isolated by mountains. While initially Grace is well received, the peaceful town shows its true nature when it realizes the vulnerability of the girl, whose escape becomes intuited by the residents because of a crime. Now Grace is submitted to successive humiliations and an unfair collective exploitation.

Dogville can be viewed as a film about the state of American society, but also as a parable about the state of Western culture, symbolized by the clash between the Jewish principle of fear of the Law and the ideal of Christian love. Making use of resources from Brechtian theatre, Lars Von Trier presents the history of the West as a history of violence and oppression.

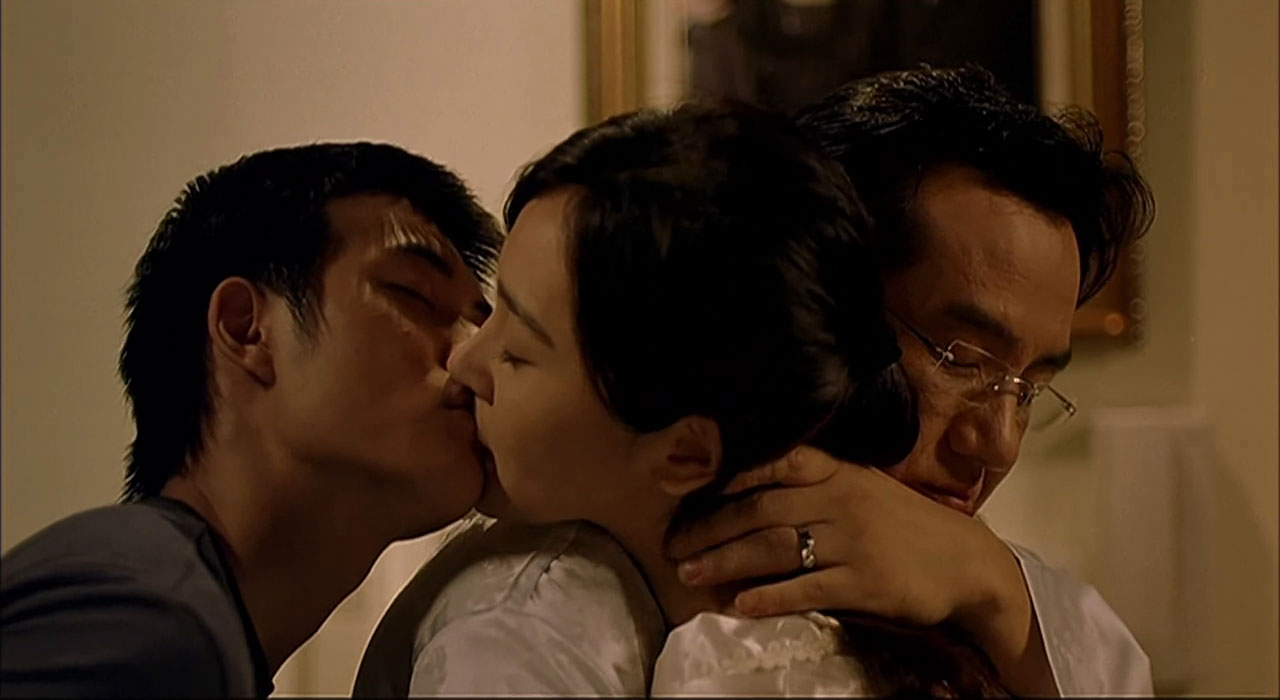

14. Oldboy (Park Chan-wook 2003)

In this film directed by Park Chan-wook, the protagonist, Oh Dae-suis imprisoned for 15 years without knowing why. Once free, he tries to unravel the reason for his imprisonment and vows revenge on the person responsible, not realizing that he is still being manipulated by him. When Dae-su finds his enemy, he i recognizes the reasons for his misery, and why he was imprisoned.

Blending elements from oriental and contemporary culture, the backbone of the film is concealed by the structure of Greek tragedies in general and in particular the Oedipus myth.

A thought-provoking and inspirational film that merges Greek tragedy and modern times, Oldboy requires us to reflect if is possible to have a tragedy without the affirmation of divine justice, and asks what the difference between action and intention might be and if it is even possible to conceive of an innocent culprit.

15. 3-Iron (Kim Ki-duk, 2004)

3-Iron portrays a young man who invades homes while their owners are away,dwelling in them for an indefinite period of time without stealing anything, just for the purpose of having a place to rest and analyze the different customs of different people. In the interim he also cleans up these houses that he lives in temporarily. In one of these raids, he encounters a girl whose married life is painful. She decides to run away with him in order to escape from her husband and the miserable life she has.

3-Iron is a film that clearly explores silence. It would not be incorrect to define it as an existential film. The way director Kim Ki-duk directs the film in a rich and detailed style appears also in some recent Eastern films. Its aim is to achieve a certain level of lyricism and mysticism.

Other contemporary films that made that kind of connection between silence and lyricism were Flight of the Red Balloon (2007) by Hou Hsiao-Hsien and Tropical Malady (2004) by Apichatpong Weerasethakul. The main objects used for this type of sensory and visual transmission are cameras, as in Blow-Up (1966).

The two characters complement each other in a unique way, trying to fill their empty and purposeless lives through unexplained attitudes. So far there are no major surprises since most of the filmsmade with that propose were influenced by the father of silence, Michelangelo Antonioni.

What becomes highlighted in the narrative of 3-Iron is the nexus between the real and the unreal. That starts to become noticeable in the middle of the film, which flows in a very natural way, little by little blurring its form, until it reaches a certain moment we do not know if one of the characters is real or a figment of the imagination of the other, createdto fill his emptiness.

3-Iron is a filmed poem, because its symbolic and lyrical nature contained in its narrative, and the film brings on the screen questions about human nature and existence.

Author Bio: Gilson Fagundes Jr. is Brazilian independent filmmaker and writer. A graduate in Cinema and Audiovisual, he’s obsessed with Asian cinema and writes cinematic reviews for several sites.