6. Black Christmas (1974)

Whilst John Carpenter’s superior ‘Halloween’ is credited for launching a new wave of slashers, it owes itself to Bob Clark’s original slasher ‘Black Christmas’. Contrary to many of the misogynist films that stole and distorted many of its aspects, ‘Black Christmas’ presented the patriarchy itself as a vulgar, anonymous villain.

A group of sorority house sisters receive threatening phone calls and are a stalked by a deranged murderer.

Who exactly is this killer? Infuriatingly for many, the true identity of the murderer is never revealed. The film revolutionised the use of the “unseen other”; it chillingly switches to the murderer’s POVs and never offers a reverse shot which allows us to identify them. Whilst such a convention would later be criticised in other films for allowing the male viewer to take on the persona of the killer, ‘Black Christmas’ used it to criticise the murder that the audience is forced to endure. The monster’s anonymity, who at the very least possesses masculine traits, proves that the patriarchy is not a single man.

The “punishment” of the female victims in ‘Black Christmas’ feels in no way deserved. What did they do? They refused to submit to the men in their lives; the protagonist’s desire to get an abortion in spite of her boyfriend’s aggressive demands is one of the driving forces behind the film. The other girls are self-reliant and sexually-liberated. In contrast, their deaths are not idealised by the camera; they’re presented for the disgusting acts that they are. The patriarchy emerges from the cold and silent night, and responds to the women’s new gained power and freedom in the only way it knows how: beastly violence.

Observed from its position in cinema history, ‘Black Christmas’ is one of the most important horror films ever made. It offered a bleak view where true evil isn’t found out there in the night but inside a woman’s own home.

7. Carrie (1976)

Brian de Palma’s teen horror stands as the first, and the best, adaption of Stephen King’s ‘Carrie’. Made during the tremulous highpoint of the Women’s Liberation Movement, the film responds to male fears of female power and sexuality in an overturning world.

A painfully shy teenage girl (Sissy Spacek), bullied at school and overly-protected by her religious and abusive mother (Piper Laurie), learns that she possesses telekinetic powers.

The film, like the novel, plays on male fears of female sexuality. The opening scene, filmed inside a girls’ locker room, establishes a fetishizing male gaze before quickly upending it. Covered in menstrual blood, mistaking it as a terrible injury, Carrie stammers around in a horrific scene which foreshadows the torturous humiliation to come. ‘Carrie’ doesn’t evoke fear in female sexuality, rather warns of the danger of neglecting it. The appearance of Carrie’s new and strange powers signals her passage into womanhood and, when repressed and misunderstood, bursts out violently.

The violent bullying carried out by her peers and fundamentalist mother both represent aggressive attempts to refrain a woman from reaching her full potential. The tragedy of the tale is that a monstrous environment has created a monster. The climatic eruption is a tour de force which is as spectacularly terrifying as it is justified. It’ a cataclysmic clash of two forces who refuse to find a middle-ground and who, as a result, will be engulfed.

‘Carrie’ was the first of over a hundred adaptions of Stephen King’s works, and remains one of the best. It’s a tragicomedy that pleas that the world ought not to implode if one woman demands to be treated fairly.

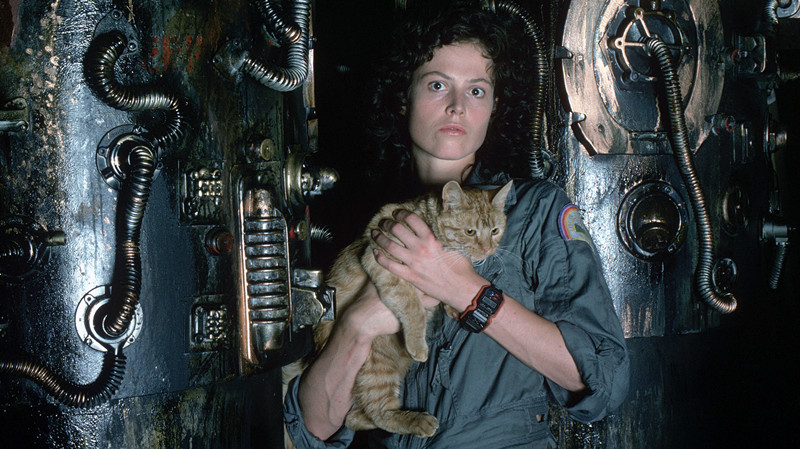

8. Alien (1979)

Ridley Scott’s creature feature stands as one of the best sci-fi horror movies ever made. Driven by a strong female lead, the movie projects feminine fears of penetration and pregnancy onto the male body.

Resembling a kind of haunted house movie set in space, the film follows the crew of the Nostromo who fall victim to a hostile extra-terrestrial lifeform after following a distress call to an isolated planet.

‘Alien’ is a frightening film because it graphically shows violation and unwanted reproduction, all of which occurs to a man. The face-hugger latches onto a man’s face and lays eggs down his throat, before a distinctly phallic-shaped creature, soaked in blood, bursts from his chest. It’s a nightmarish reinterpretation of pregnancy where the mother is a man.

There’s disfigured sexual imagery to be found throughout H.R. Giger’s design of the parasitic alien and the planet where they find it. Ultimately the male viewer is forced to experience anxieties usually attached to women.

Compelling too is the role of Ripley, who assumes leadership and is the only human to survive. Subverting several of the masculine clichés found in adventure movies, Scott offers a heroine equally resourceful to any man, and a bizarre monster which is neither male nor female but both.

‘Alien’ is one of the most frightening films ever made. In the end gender is no guarantee of safety from a terrible monster or the lonely vacuum of space.

9. A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984)

‘A Nightmare on Elm Street’ has become the signature film of horror master Wes Craven. Challenging “the Final Girl” and “Terrible Place” conventions found in the genre, Craven offered an almost feminist take on the modern slasher.

A group of teenagers are stalked by a sadistic murderer who aims to kill them in their own dreams.

Freddy Kruger, now an icon of cinema, is the embodiment of the white patriarch. Despite offering glimpses of humour in his occasional wisecracks, he’s ultimately vial. The dreamish camerawork uses few killer POVs and neither identifies nor sympathises with him. Craven instead presents Freddy as an omnipotent evil: a shadow on a wall, a metal glove scraping along a pipe. The movie evokes fear in the patriarchy; a villain who murders and molests and is neither here nor there but everywhere.

Heather Langenkamp’s Nancy is a strong female character who destroys Kruger despite lacking masculine traits and aid. Most empowering is how she does it: simply by refusing his gaze and denouncing him. Remove the fear that it evokes, and the myth of male dominance loses any substance.

‘A Nightmare on Elm Street’ well deserves its iconic status. In a world where dream and reality collide, no man or monster holds superior ground.

10. High Tension (2003)

Alexandre Aja’s ultra-violent horror is a seminal work of the French Extremity Movement. Bloody and polarising, the film hacksaws through any set notion one might have of gender identity.

Launching off as a typical slasher, it watches two (female) college students, Marie and Alexa, go on vacation and stay with Alexa’s family. That night, their isolated home is invaded by a psychotic (male) murder.

The movie’s twist, which reverses the gender polarity, takes the movie into a far more shocking albeit unbelievable place. It’s hard to swallow for two reasons: 1) It seems random, illogical and contradictory and, 2) It aggressively destabilises our definition of gender. It’s a bifurcated, postmodern approach to the genre which makes you wonder: Must the dominant role of the murder be defined as masculine and must the vulnerable role of the victim be necessarily feminine?

The film itself seems little interested in answering these questions. It prefers to stab and to grind gender identity until it’s a bloody pulp; no reason is needed. Aja establishes a polarity between a terrifyingly violent man and a strong, resourceful woman, before collapsing the characters into a single personality. Male and female are at last one.

‘High Tension’ certainly delivers on its name. Bearing similarities to the later and equally brutal French slasher ‘Inside’, it offers the message that sexuality is as fluid as blood, and gender as malleable as flesh.