8. Branded to Kill (1967, Seijun Suzuki)

While serving in the Japanese Imperial Army during World War 2, the American Air Force sunk a freighter with the aforementioned Seijun Suzuki onboard. He later he explained that to him, “war is very funny, you know! When you’re in the middle of it, you can’t help laughing… I was thrown into the sea during a bombing raid. As I was drifting, I got the giggles. When we were bombed, there were some people on the deck of the ship. That was a funny sight.” He was rescued after treading water for eight hours.

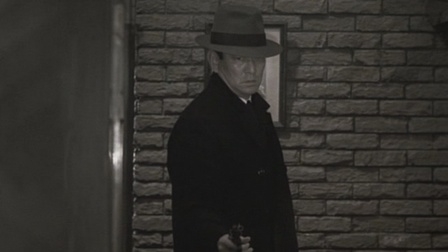

That somewhat maniacally frightening ability to find comedy in such situations evidently shaped his magnum opus, Branded to Kill. Death lingers and hangs over every scene, as a brutal spectre that haunts every perverse and hallucinatory shot. Yet so does a dark, guilty humour.

Shishido returns as Suzuki’s protagonist, this time as Hanada, again a contract killer though this time with an unappeasable erotic desire for boiled rice. At this point it’s worth including the obligatory acknowledgement of Shishido’s cheekbones, the envy of chipmunks the world over. After a botched job, Hanada stumbles into meeting Misako, a woman who quickly becomes a client with a list of three people to be dispatched.

From there however the film unravels further and further as murderous, perverted and hypnagogic sequences play out and a battle of wits ensues starring dead butterflies, a boxing ring and the mob’s enigmatic top hitman, Number One.

It’s a film that would stand out as absurd and bizarre amongst the filmographies of Melville, Godard or Buñuel, yet the tranquil and sharp-cornered camerawork, even while what’s on screen is chaotic and maddening, tells you that it is steeped deeply in the mind of someone who has giggled at death before. Hailed today as a masterpiece, this was the film that got Suzuki fired from Nikkatsu. No surprises there.

9. Death by Hanging (1968, Nagisa Oshima)

Capital punishment, state violence, sexual violence, war crimes, murder, institutionalised racism; a lesser director would have collapsed under the sheer weight of Death by Hanging’s themes. Not Nagisa Oshima. Instead he creates a Brechtian paragon. He presents his subject matter through the botched execution of R, a twenty-three year old based-on-a-real-case ethnic Korean accused of raping and murdering two Japanese girls.

Having survived his hanging but lost his memory, a priest, prison guard, doctor, prison education officer, public prosecutor and an assortment of witnesses attempt to reason him back into consciousness.

Technically the obvious influence is Godard but the crux of the film is drawn from the Theatre of the Absurd. The supporting cast’s extraordinary repartee reaches the height of verfremdungseffekt as they attempt to re-enact R’s childhood and crimes to remind him of who he is. Their pantomimes highlight the inefficaciousness of killing killers but capital punishment is lightweight compared to some of the other themes Oshima has in his sights.

As the film goes on characters reveal a conflict between the profoundest guilt for their own war crimes and centuries of Japanese oppression of Koreans and their attempts to acquit themselves through ultra-nationalism and a racial superiority complex. This is the post-war society not so much being critiqued or dissected but violently mauled.

10. Boy (1969, Nagisa Oshima)

Chronologically sandwiched between the absurdity of Death by Hanging and the international controversy of In the Realm of the Senses, Oshima’s Boy has at times been dismissed as a backwards step both thematically and cinematographically. There is however much more of both style and substance here than is often recognised.

Based on newspaper clippings its director collected, the film centres around a ten year old boy, seemingly with no name, and his emotionally and financially dysfunctional family. His father is an indolent veteran, claiming to have been rendered invalid by his war injuries and his step-mother is a broken woman, paralyzed by the fear of not being loved. The pair force the boy to throw himself at passing cars in order to be able to extort money for ‘hospital bills’ out of the drivers.

Like the previous entry, Boy deals with those left behind as the bullet train that was Japan’s economic miracle zoomed into the distance. The film’s lead is Testuo Abe, an orphan who was living in a Tokyo children’s home when cast for the part. He spends much of the film on the outsides of shots, both at the edge of the frame and the edge of society.

It’s a story of loneliness and the anxieties of abandonment. The boy draws enjoyment and relief from his escapist fantasies, telling his baby brother about men from outer space who would use their cosmic powers to right wrongs. However the little green men never arrive and the family are left to fend for themselves in whatever way they can.

Oshima doesn’t condemn them; they are not evil or hateful, simply desperate. For him his role is to observe and empathise, challenging his audience to discard previously held prejudices or preconceptions.

11. Battles without Honour and Humanity (1973, Kinji Fukasaku)

From the blood red opening titles over black and white stills of the destruction wrought by the atomic bomb, it is obvious that the first of Kinji Fukasaku’s pentalogy is going to be something different.

Whereas previous Yakuza films had frequently glorified the apparently strict codes and oaths of the criminal world, Battles strips them of their romance and mythology. Chaotic ultra-violence is melded with dark humour as the unrelenting and exaggerated plot speeds through a decade of Hiroshima’s competing mobster families.

The film goes to great lengths to eschew the meticulously framed compositions of traditional Japanese cinema made famous by Kurosawa and Ozu. Whereas their shots are often stationary or restricted in their movement Fukasaku goes handheld, putting audiences in the middle of brawls and preferring close ups when the pistols are drawn and the tantōs unsheathed.

At times this is abandoned for documentary style stills and voiceovers, with accompanying text to give dates of murders. This presentation both draws from and lends itself to the source material, a series of newspaper articles based on the writings of a genuine Yakuza.

As William Friedkin would later say when discussing his influence, Fukasaku never felt the need to ‘redeem the good guys.’ Indeed there are no good guys in Battles. No great victories either, just an eternal struggle for supremacy, each assassinated rival replaced by a new, more unpredictable foe. Seeing past the rhetoric of sacred vows there’s no honour or humanity, just a pile of corpses. The dead are all victims of their own greed and the greed of those they were calling ‘brother’ just a few scenes before.

12. Vengeance is Mine (1979, Shohei Imamura)

Shōhei Imamura’s Vengeance is Mine is often compared to Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood and its subsequent film adaptation. It’s true that both deal with a hauntingly violent murder spree and those who committed the crimes and that both excel in painting portraits of the society that bore witness to heinous the crimes. But the similarities stop there. Capote sought to understand and ultimately came to sympathise with at least one of his subjects, whereas Imamura wanted only to observe.

Under his microscope is Iwao Enokizu (based on serial killer Akira Nishiguchi and played by Ken Ogata), introduced while being driven to a police station having been arrested after a string of murders and a high-profile manhunt that lasted over two months.

A media gaggle is waiting for him but they won’t get any words out of him. They won’t get anything out of him, not today, not ever. The first thing that strikes you is his sheer normality, then his blasé and frankly uncaring facial expression. He reveals nothing. Not outside the station, nor inside under interrogation nor throughout the flashbacks of his crimes and childhood that follow.

Imamura’s background in documentaries is plain to see. His still, middle-distance shots of Enokizu’s murders are there to present a factual account of his fictionalised tale. The film ultimately becomes a tidal wave of intensity as it becomes clear that it is not heading towards a neat, understandable conclusion. He is something to be feared above all else, an undiagnosable monstrosity.

13. Demon (1985, Yasuo Furuhata)

Now unjustly overshadowed by the unfortunately timed and named Italian horror film Demons (also 1985), Yasuo Furuhata’s character driven drama is a calm, unhurried story of people’s past lives catching up to them. Its strengths very much lie in its performances, pitting hardman veteran and four time Japan Academy Prize winner Ken Takakura against the then next big thing Takeshi Kitano (credited under his acting pseudonym Beat Takeshi.)

They are Shuji and Yajima. The former is a retired Yakuza whose only connection to his past is the telltale Yasha (demon) tattoo on his back. When he moves to a tranquil seaside town wanting to start anew as a fisherman his arrival coincides with that of Yuko Tanaka’s Keiko, who opens a bar under the unsubtly symbolic name Firefly. Sure enough the local men are drawn to her but she too is running, though not fast or far enough to escape Yajima, her heroin addicted ex-gangster lover.

As the waves crash against the shore the film’s conflicts are accentuated by the contrast of the anxieties and dangers of these three battered souls and the serenity of the coastal life around them. The significance of Shuji and Yajima’s potentially deadly antagonism is grounded in more than jealousy.

The older Takakura embodies the oldschool Yakuza, defined by a cool brutality and dedication to duty. Kitano (who will later be discussed in more detail) brings a malicious, vicious and rapacious presence to proceedings. His drug-fuelled knife wielding rampage is worth the price of admission alone. These three characters are humanised though not romanticised, a rare feat that can only be the product of talented direction and a supremely talented cast.

14. Sonatine (1993, Takeshi Kitano)

There are few greater injustices in cinematic history than the fact that Takeshi Kitano is better known outside of Japan for the catastrophic sci-fi box office bomb Johnny Mnemomic than the extraordinary Sonatine.

The latter is a work of minimal mastery. Kitano directs and stars as Murakawa, a mob boss exhausted with the Yakuza lifestyle, asked by his superiors to travel to Okinawa to ensure a potentially explosive disagreement doesn’t escalate. All he really wants though is to retire. He agrees, despite suspecting a double cross. When the job becomes violent he and a few comrades retreat to the seaside.

What follows is essentially a gangster’s holiday. He and his band of killers and thugs play practical jokes on each other and throw a frisbee on the beach. It was wrong to say Kitano “stars as Murakawa”, as he doesn’t star so much as lingers. He is a tired, beaten man, uncaringly drifting towards an unknown fate. It’s a performance of few words but mountains of gravitas.

Sonatine’s direction is a lesson in perspicacity, as the film finds a fascinating and original story about the Yakuza lifestyle that so many have dealt with before. It’s the existential, brooding yet lyrical meditation of a character who has come to resent his life, and it’s flawless.

15. Fireworks (1997, Takeshi Kitano)

A year after making Sonatine Kitano crashed his motor scooter in what he later described as an ‘unconscious suicide attempt.’ Having not been wearing a helmet his injuries left one side of his face paralyzed. As part of his recovery he began painting, experimenting with a colourful, unostentatious style. His accident informs and runs through every facet of Fireworks.

Kitano crosses the line of criminality to play Nishi, a detective haunted by tragedies of Elizabethan proportions. His daughter’s death at five years old, his wife’s losing battle with leukaemia, a colleague’s death and another’s paralysis at the hands of a murderer have left him appearing from the outside to be little more than a shell. However it quickly becomes obvious inside is a vicious rage.

The film cuts from a serene calmness to bloody violence at an unsettling and at times shocking rate. Nishi is evidently struggling through life yet revels in often unjustified acts of brutality.

Kitano’s own paintings feature heavily and one feels this is a fictionalised autobiography, the imaginary diary of a man whose real life had taken a highly consequential and difficult turn for the worse. This is a crime drama in which the dramatic consequences of crimes as opposed to the acts themselves take centre stage. Every character’s inner turmoil tears at them, telling an introspective tale that is at its core distinctly human.

Author Bio: Jamie Lewis is a teacher and wannabe film critic. He collects sunglasses and tweets pictures of people in cars from films. You can follow him on Twitter @jamielewisPM.