It’s always exciting to hear what the next project of your favorite director will be. Sometimes it’s an enticing prospect, a story that takes the filmmaker’s established work in a new direction. Sometimes it’s a perfect fit, something that plays to the director’s strengths. Sometimes, it’s a puzzling decision that leaves you scratching your head, befuddled.

This list will explore some of the more unexpected combinations of director and material. In several of them the connection is apparent once you scratch beneath the surface. In others, what attracted the director to the material remains a mystery. In all cases, the result is more interesting because of the different creative forces it draws from.

It could also be a reminder that most directors are primarily concerned with finding a good script that would make a great movie. More often than not, they turn to familiar themes and styles that they are passionate about and are proficient in. When they don’t, it is the fans, critics and scholars that analyze their choice and try to incorporate it into their established body of work.

15. Peggy Sue Got Married – Francis Ford Coppola

Coppola is mostly known for his vast, violent, operatic epics – The Godfather trilogy and Apocalypse Now. Most of his other works relate to his trademark masterpieces – The Conversation is another exploration of a dark underworld, where men control and destroy lives outside of the public eye.

Dracula is lush and passionate, exhibiting the same grandness as Coppola’s most popular titles. The Cotton Club and Tucker: The Man and his Dream offer dark explorations of the American Dream. In One from the Heart Coppola plays with cinematic conventions of colors and compositions, an experiment that fits well along with his more recent indies.

Against these themes, the sweet, Capra-esque Peggy Sue Got Married is an anomaly. In it, a soon to be divorced mother travels back in time to her teenage years after fainting at her high school reunion. It is Coppola’s only feature length work led by a female protagonist.

This disparity isn’t felt in the film. Coppola finds the perfect tone: a dreamy yet cynical wistfulness, aided by a radiant, game Kathleen Turner. It’s a challenging performance, as Turner must relate to other characters and herself on many levels – the teenager she was, the grown up she is and the grown up she wishes to be. The film, uncharacteristically for the genre, explores the true emotional weight of time travel.

As Peggy Sue encounters childhood friends before the mistakes and victories that cemented their lives, her parents, younger than she’s seen them in years and her long dead grandparents, a rich poignancy permeates the film, lending gravitas and meaning to the plots proceedings.

As a bonus point, look out for a young Jim Carrie, the buds of his masterfully outlandish use of body and face in clear display.

14. Misery – Rob Reiner

In screenwriter William Goldman’s memoir Which Lie Did I Tell? he regales the process of finding a director for his screenplay adaptation of Stephen King’s Misery. Goldman and the film’s producer, Rob Reiner, approached practically every director in Hollywood, to no avail. Goldman says Reiner eventually said something along the lines of ‘screw it, I’ll direct it.’

Up until then Reiner was mostly known for directing comedies (This is Spinal Tap, The Princess Bride), romantic comedies (When Harry Met Sally…, The Sure Thing) and the poignant coming-of-age film Stand by Me – another Stephen King adaptation. Goldman’s story seems to suggest that Reiner hadn’t had an innate interest in directing Misery.

Perhaps he felt his sensibilities were wrong for King’s violent, twisted thriller about a writer who finds himself at the mercy of his deranged ‘Number 1 fan’. However, a close examination of “Misery” might suggest the opposite – Reiner’s approach may be exactly what sets the film apart and above similar films.

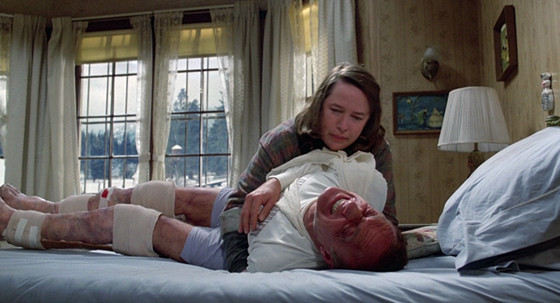

Misery could easily be read as a dark romantic comedy. Like Harry and Sally, Paul (James Caan) and Annie (Kathy Bates) meet thanks to circumstance, grow closer and get to know each other. For most of the film they go back and forth between getting along and growing apart. The only difference is when Harry offends Sally she cuts him out of her life.

When Paul offends Annie, she applies a sledgehammer to his feet. But even that gruesome scene – a favorite of Goldman’s – ends with Annie telling Paul that she loves him. The way Reiner and Bates play it, she fully means it.

Reiner masterfully paces the story, leaving room for characters and humor, but keeping the suspense taut and ever-present, especially in a cross-cut sequence where Annie is on her way home while Paul is wandering outside of his cage.

Reiner, Bates and Goldman make Annie a victim of her psychological problems, rather than a typical, cackling villain. This approach makes Annie richer and provides Bates with a perfect chance to create a compelling, complex character. This unique pairing between director and material makes ‘Misery’ unique, a more sensitive and definitely funnier thriller than most of its ilk.

13. Vanilla Sky – Cameron Crowe

Cameron Crowe won a well-deserved Oscar for writing the wise, funny and poignant semi-autobiographical Almost Famous. That movie felt like the consummate Crowe movie, intertwining styles and themes from his previous films: sincere explorations of relationships, astute examinations of how and why we fall in love and a passion for pop music, expressed in carefully crafted soundtracks. Crowe surprisingly followed that victory with Vanilla Sky, a remake to the dark, twisty, Spanish sci-fi thriller Abre Los Ojos (Open Your Eyes).

Open Your Eyes tells the story of César, a successful young man whose face is horribly disfigured in an accident. As he tries to piece his life back together, he gets more and more paranoid and his grasp on reality withers. Eventually César realizes he is living in a dream. He chose to freeze his body until his face can be fully restored. The universe he inhabits is the entertainment selected to keep his brain engaged while in a coma. It is a fascinating exploration of reality and identity.

Vanilla Sky keeps all of its source’s sci-fi themes, but Crowe adds his own touches. He employs the savviest use of Tom Cruise’s star persona since “Magnolia” – if you’re going to destroy an actor’s face, who better than Cruise? Whether hidden behind a ball mask, exhibiting his disfigured face or plucking a single gray hair off his head, Cruise’s looks aren’t just used, they are explored. “Vanilla Sky” delves into the deterioration of a grand male ego.

David’s fictional universe is made out of images, lines and tunes his mind picked up from album covers and movies. His mind replays the accident that destroyed his face and populates his dreamscape with the two women in his life. One is the unhinged Julie (Cameron Diaz), scorned by David’s selfish, ego-driven relationship with her, which compelled her to crash the car they’re in, destroying David’s face. The second is Sofia, (Penelope Cruz), David’s true love, healer and redeemer. As David’s dreamscape devolves into a nightmare, these women slowly collapse into each other, melting their identities together.

Crowe uses the reality bending concept of Open Your Eyes to depict the destructive and restorative power of love and how often and easily they become indistinguishable. He also looks into how we use pop culture to shape our lives, borrowing from a collective consciousness to create our own narratives, images and feelings.

12. Punch-Drunk Love – Paul Thomas Anderson

Paul Thomas Anderson broke out with Boogie Nights and Magnolia, both rich ensemble pieces. They explored the dark and seedy corners of the hearts of the many characters inhabiting them. These characters were often trapped in hopeless situations – emotional, romantic, and financial – that they had little hope of escaping. Imagine the surprise when it was announced that Adam Sandler will headline Punch-Drunk Love and the film would focus on his frustrated attempts at wooing a romantic interest.

This logline might be a bit misleading in this case. Yes, the movie focuses on Barry Egan’s attempt to control his anger and manage the many fraying threads of his life, so that he can date Lena (Emily Watson). But this movie is far from what could be dubbed a ‘romantic comedy’.

In a way, this is the inverse of the aforementioned connection Rob Reiner had with “Misery”. Reiner used his rom-com sensibilities to give the psycho-thriller a new angle; Anderson infuses a rom-com with his intense cinematic style and attraction to inhibited, frustrated masculinity and sordid characters.

One of the most interesting things about the movie is how easily it fits in with Sandler’s previous characters. Barry Egan is a good hearted loser, who tries to express himself romantically and cannot – because of his innate violence. It’s almost as if Happy Gilmore grew up and got a sales job.

Apart from Lena, Egan must also contend with his seven emasculating sisters, his quest for free airline miles and a petty criminal (the late Phillip Seymor Hoffman) out for his money.

The screenwriting, editing – image and sound – techniques Anderson employs, craftily convey the pressure Egan feels at all times, playing with our expectations and suspense as to when and how he’ll cut loose. It is this intensity that lends “Punch-Drunk” its edge and its comedy. When Egan’s anger is used productively for once, it frees him up to freely reunite with Lena.

11. Birdman – Alejandro González Iñárritu

Birdman is the sharp, funny, surreal presentation of the final days leading up to the premiere of Riggan’s (Michael Keaton) Broadway debut as an actor and director. This is his comeback since he fell out of the spotlights upon refusing to do another film in his hit superhero franchise ‘Birdman’.

The movie, shot in what is made to look like one continuous shot, follows all the characters involved in his life – daughter, lover, fellow actors, a critic, his manager – as they bounce off each other like balls on a pool table, ricocheting off in new directions. In addition, Riggan himself seems to be losing touch with reality, as he is haunted by his ‘Birdman’ superhero character, who keeps whispering in his ear.

The result touches upon issues clearly close to director Alejandro González Iñárritu’s heart: the role of critics, the relationship between art and popularity, an artist’s need for validation and approval. However, what keeps Birdman engaging and enjoyable, is the levity and deceiving nonchalance in which it unfolds.

This is also true stylistically – while we are aware of the amazing feat of setting up these separate long shots, the film connects them seamlessly and naturally. The continuous take infuses the film with an energy that keeps it light, at least until the final act, when Riggan’s grasp on reality deteriorates.

Levity is scarce in Iñárritu’s body of work. He is known more for interlocking tragic stories in Amores Perreros, 21 Grams and Babel and for Biutiful, a lyrical examination of a dying man parting from this life. Not the stuff showbiz comedies are made of.

This isn’t to say serious themes and humor are mutually exclusive – but Iñárritu’s films have always been dead serious. They often incorporated social and political issues into the mix and focused on the important message they tried to convey. A far cry tonally from “Birdman”, which feels like a lost 70s cooperation between Robert Altman and Woody Allen.

10. Starman – John Carpenter

John Carpenter is known for his unique combinations of horror, sci-fi and often action and comedy. While some of his films are the scariest ever made – the seminal Halloween, The Thing – others of his works mix thrills and imagination with lighter touches – Big Trouble in Little China, Dark Star.

Many of his films deal with male camaraderie – The Thing, Dark Star even Christine is in many ways about the tensions between two vastly different high school best friends. In the Oscar-nominated “Starman” Carpenter crafts another exciting sci-fi yarn, but takes it in a direction you wouldn’t necessarily expect from him.

An alien comes to earth on an anthropologic mission and his spaceship crashes. It engages Jenny, a widow (Karen Allen), to help it get back to his planet. To make her more at ease, the alien assumes the shape of her recently deceased husband (Jeff Bridges). Together they drive from Wisconsin to Arizona, hoping to get the Alien in time to catch his ride home. Suspense is provided by the determined campaign of the army to capture the alien.

The heart of the film is the relationship that evolves between the two. Jenny’s feelings about going along with this entity change constantly. At first she’s being kidnapped. Later, she agrees to help the stranded alien that looks like a man she loved and lost. As the alien learns more about mankind, and adapts more of her husband’s mannerisms, Jenny’s emotions become even more complex.

As the Alien learns more about humanity, bringing in echoes from The Day the Earth Stood Still, he falls in love with her. The different layers in how their emotions evolve shifts this somewhat hokey sci-fi concept away from Carpenter’s typical genres and well into the realm of relationship drama. It is a testament to Carpenter’s delicate hand and Allen’s and Bridges’ sweet, committed performances, that when these characters say goodbye, it resonates with and means something to the audience.

9. Match Point – Woody Allen

From all the filmographies discussed on this list, Woody Allen’s is perhaps the most distinctly recognizable. Nearly all his movies star him or an avatar of his unique persona. They universally deal with the emotional issues of intellectual bourgeois, whether in their natural habitat (New York), or thrown into foreign territory (czarist Russia in Love and Death, the future in Sleeper).

Match Point features no Allen avatar. Instead, its protagonist is Chris (Jonathan Rhys-Meyers), an affluent, successful, engaged young man who meets Nola, a beautiful woman he can’t resist (played by Scarlett Johansson, so who can blame him?). They have an affair. When the affair progresses and Nola threatens to blow the whistle on their tryst, murder starts to cross Chris’s mind.

This inner deliberation and its results are the heart of Match Point. Allen uses this story as a platform to explore morality, guilt and the indifference of luck and fate to these so-called weighty issues.

Allen has tackled murder and morality before in Crimes and Misdemeanors, one of his best movies. However, that movie featured a comical subplot to even the tone. Match Point is more of a straight thriller and offers no such respite. Its dark sense of irony doesn’t produce chuckles, but rather twists around our necks. It is a dark movie that seems to suggest something far more chilling than most murder movies dare: you can get away with murder, and if you do, the world will keep on spinning idly by.