8. Thelma & Louise – Ridley Scott

At first glance you could make a case for a history of prominent female characters in Scott’s oeuvre: tough as nails soldier Demi Moore in G.I.Jane and of course the iconic Ellen Ripley in Alien. A wider look exposes Scott’s fascination with men in uniforms and male camaraderie, from his debut The Duelists through White Squall, up to later works Black Hawk Down and Kingdom of Heaven.

G.I.Jane definitely falls neatly into this category, its female hero exhibiting masculine attitudes in a masculine environment. Scott is also drawn to vast epics (Gladiator, 1492) and almost Michael Mannish cat-and-mouse relationships (Blade Runner, American Gangster, Body of Lies and Hannibal, which unlike its predecessor shifts the point of view from detective to killer). Thelma and Louise doesn’t quite correspond with these themes.

In Thelma and Louise two unhappy women go together on a road trip. Things take a turn for the worse when Thelma is almost raped and Louise shoots and kills the rapist, causing the two women to go on the run. The rest of the film is a thriller, yes, but it also explores their interactions with several male characters: The cop who is chasing them but also tries to save them (Harvey Keitel), Louise’s husband (Michael Madsen) who does his best to help but can’t quite pull her back from the ledge she’s on, a charming con artist (Brad Pitt) who essentially dooms the women and many others. “Thelma and Louise” is a film that explores women’s place in a world dominated by men.

Thelma and Louise makes for an interesting choice, considering Scott’s affinity for male-dominated systems (police, military). Consider Alien, where Ripley clearly belongs in the world of space truckers, even more than her teammates, as she proves by surviving them. Or Blade Runner, where the main female characters were created by men and neither are offered the same existential depth the two male leads – human or mechanic – have.

It is interesting that a director preoccupied with spaces controlled by men, made Thelma and Louise, a film which seems to tragically suggest that women who refuse to succumb to the roles offered them, find themselves pushed away from these very spaces or worse, destroyed by them.

7. American Graffiti – George Lucas

It’s somewhat surprising to discover that George Lucas has only directed six feature films: his debut THX 1138, based on his short film project while still a student at USC, four of the Star Wars films (A New Hope and the new trilogy) and American Graffiti. He was also a crucial creative force behind creating the basis for the character and world of Indiana Jones. Between these sci-fi and adventure tales, ”American Graffiti”, a weaving of small, intimate stories of several high school students after graduation, seems rather peculiar.

It isn’t just the genre and tone that seem different. Arguably, no other filmmaker has managed to distill the mono-myth presented in Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces more successfully than Lucas has, repeatedly, with the Star Wars series. Campbell presents a theory stating that all ancient mythologies are essentially the same story. This story revolves around one hero, on a specific quest with several familiar and mandatory stops on his way (‘The Call for Adventure’, ‘The Ultimate Boon’, ‘The Magic Flight’, etc.). The unprecedented success of Star Wars made this story theory very popular and Lucas its poster boy.

Compare that with the rotating ensemble of characters and narratives in American Graffiti. All of them have a problem they start out with (Curt can’t decide if he wants to leave for college or not, John gets stuck with a pre-teen in his car, Terry tries to pick up a girl, etc.), they don’t quite go on a quest to achieve it as they meander around town in circles. In that sense American Graffiti is more of an American 70s movie than a Lucas film. It shares the same narrative and cinematic sensibilities exhibited at the time by filmmakers such as Robert Altman.

American Graffiti successfully distills baby-boomer nostalgia and then scratches underneath its surface. What it finds swings between nostalgic and innocent, to ironic and sad. The epilogue, off-handedly showing us the fate of the characters whose travails we followed so closely, is both nihilistic and comforting. It suggests that all those minute post-high school quests we followed don’t matter much in the grand scheme of things, for better or worse.

6. Body Heat – Lawrence Kasdan

Lawrence Kasdan is one of the most prominent screenwriters of the 1980s. He is mostly known for writing-directing small dramedies, focusing on relationships and emotionally complex individuals (The Big Chill, The Accidental Tourist and later Grand Canyon). He also wrote and directed two westerns (Silverado, Wyatt Earp) and wrote three of the biggest, most successful, most enjoyable action-adventures in movie history: Raiders of the Lost Ark, The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi. However, his directorial debut doesn’t relate to this. It feels like an isolated piece of work, its themes never revisited by Kasdan.

Body Heat is a post-modern noir. It is just shy of being a Double Indemnity remake, and definitely takes its narrative cues and character development from 40s film noirs. Whereas other pinnacles of neo-noir – Chinatown, L.A. Confidential – mix historical and political statements, as well as several subversions of genre conventions, Body Heat aims to be the real thing, to appear like a lost specimen from the peak of Film Noir.

It succeeds. From Kathleen Turner’s perfect femme fatale (‘You aren’t too smart, are you? I like that in a man.”), through William Hurt’s overly confident sap, the Florida setting, the heat wave that permeates every frame straight to the twisty climax. The final shot on its own serves as a summation of the femme fatale as an embodiment of patriarchal fear and female independence.

5. The Bridges of Madison County – Clint Eastwood

Most of the films Eastwood directed before The Bridges of Madison County were westerns or thrillers. Yes, there were exceptions: Some dealt with music (Honky Tonk Man, Bird), some were biographical (Bird, White Hunter Black Heart). All of them featured a lone, tough man, on the outskirts of a community, with a code of his own.

After he made Unforgiven the most critically acclaimed film of his career at that point, which also won him Best Picture and Best Director Oscars, he started to experiment with new themes and settings. One of these experiments is The Bridges of Madison County.

Although the book received some good reviews, many considered it sentimental. Not a very Eastwood-y adjective. The movie is a romantic drama focusing on a short 4-day affair between Francesca, a lonely, married Italian woman in Iowa (Meryl Streep, giving a strong nuanced performance as always) and Kincaid, a travelling National Geographic photographer visiting town for a project (Eastwood).

Kincaid definitely corresponds with Eastwood’s previous characters. In his many conversations with Francesca, he expresses his world view – he never feels lonely, he has friends everywhere, he enjoys existing without a community. However, if previous Eastwood loners were contending with issues of duty, redemption and justice, Kincaid has to contend with real, once-in-a-lifetime love. It is Francesca who must grapple with her feelings of duty.

Unforgiven is fascinating because of how it went against old western values. Eastwood’s character in it abhorred violence even as he used it to avenge his friend. This older, contemplative examination of his star image, of the values his characters and films inhabited is part of what makes Eastwood’s later work so interesting. The Bridges of Madison County allows him to explore what would make his archetypical drifter settle down. That may be why the project appealed to him.

4. Hugo – Martin Scorsese

Let’s cut to the chase here. Hugo has no mafiosos, no overly ambitious men building empires, no dark New York Streets, no gangsters, no cops, no violence. Yet it displays one of Scorsese’s deepest passions – cinema itself. Hugo is a love letter to cinema and a chance for Scorsese to put a spotlight on one of its founding fathers – Georges Méliès.

The movie doesn’t start with Méliès, but rather arrives at him through Hugo, an orphan that lives in the tunnel of a Parisian train station. He is hounded by the station’s inspector (Sacha Baron Cohen). After he is caught stealing, he is forced to work with an angry old man (Ben Kingsley), to earn back a prized souvenir from his father.

Hugo gets to know the old man and his adopted daughter, Isabelle (Chloë Grace Moretz), who helps Hugo unravel mysteries surrounding his dead parents. Together they discover the old man is actually Georges Méliès, one of cinema’s pioneers. Méliès, angry and bitter after being left in the cold, wants nothing to do with his past. With the help of a friendly film scholar (Michael Stuhlbarg), Hugo and Isabelle make sure Méliès receives the status he deserves.

Hugo is an earnest coming-of-age film. It is through Hugo’s eyes that we get to see the pain Méliès harbors in his heart every day. As Hugo and Isabelle help him, Hugo also learns about his family and reaches a point of acceptance that allows him to start a new, better life.

If the genre and themes aren’t typical of Scorsese, the style is. Long tracking shots, energetic camera movements and rapid editing are all well embedded into Hugo’s cinematic syntax. Hugo is Scorsese’s first (and so far last) foray into 3D and the film employs a great deal of CGI. Scorsese is clearly having a ball with these new tools at his disposal and Hugo is all the richer for it.

It seems only fitting that Scorsese, one of our most virtuoso directors and cinema’s most avid students would use all the effects possible to craft a film that would honor Méliès, the forefather of visual effect. This wonderful union is nowhere better expressed than in a touching shot near the end of Hugo, when Méliès as played by Kingsley, morphs into the real Méliès acting in one of his real films, seemingly without a cut.

3. The Curious Case of Benjamin Button – David Fincher

David Fincher, patron saint of dark shadows, serial killers, predatory men (and a woman), sets out to direct the whimsical tale of Benjamin Button, a man who ages in reverse. It is a tender musing about age and death, love and time. The Curious Case of Benjamin Button does feature a rich, dark palette (created by DP Claudio Miranda) and it offered Fincher a technical challenge, which he likes to tackle (the Winklevi in The Social Network, for example). But that’s pretty much where “Button’s” obvious connection with Fincher’s filmography ends.

Born an old man, Benjamin Button (Brad Pitt) struggles to find his place in the world. He has the mind of a child and the body of an old man. Throughout the film Button finds himself in myriad locales – he modestly participates in World War 2, he has an affair in Russia with the wife of the British Trade Minister and travels third world countries as a teenager.

The thorough line of all these adventures is the push and pull of his relationship with Daisy (Cate Blanchett). They meet when she is six – the movie speeds by the creepiness of Button ‘loving her at first sight’ – and their relationship evolves as they age, each in their own way. When they meet in the middle, they find paradise in a small apartment, where they celebrate their youth, love and freedom.

Aside from “Button” being a thematic divergence from Fincher’s work, it is also a narrative one. The film has an episodic, meandering feel which is natural for its ruminations about life, love and time. The film spans a lifetime, so it makes sense for its structure to be more diffused. Fincher, on the other hand, is known for his taut clockwork thrillers. He has tackled his share of complex narratives: the multitude of flashbacks in The Social Network, the span of decades in Zodiac and most recently, the welding together of different POV’s in Gone Girl. But if anything, they resulted in even more restrained and focused narratives.

The film was a success for Fincher. It received thirteen Oscar nominations including Best Picture and Best Director, the first for Fincher. It would end up winning three in technical categories. It made solid business and received good reviews. Nevertheless, from the vantage point of 7 years past, this film has not received the enduring status of Fincher’s earlier films.

2. The Fisher King – Terry Gilliam

Terry Gilliam is known as one of the major creative forces behind the absurdist Monty Python comedies, as well as the helmer of such surreal escapades as The Adventures Of Baron Munchausen, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas and the dystopian Brazil. It is hence surprising to find The Fisher King in his filmography. While the movie does have a few short moments of fantasy, it is a quiet story about coming to terms with grief and guilt and slowly developing responsibility and relationships.

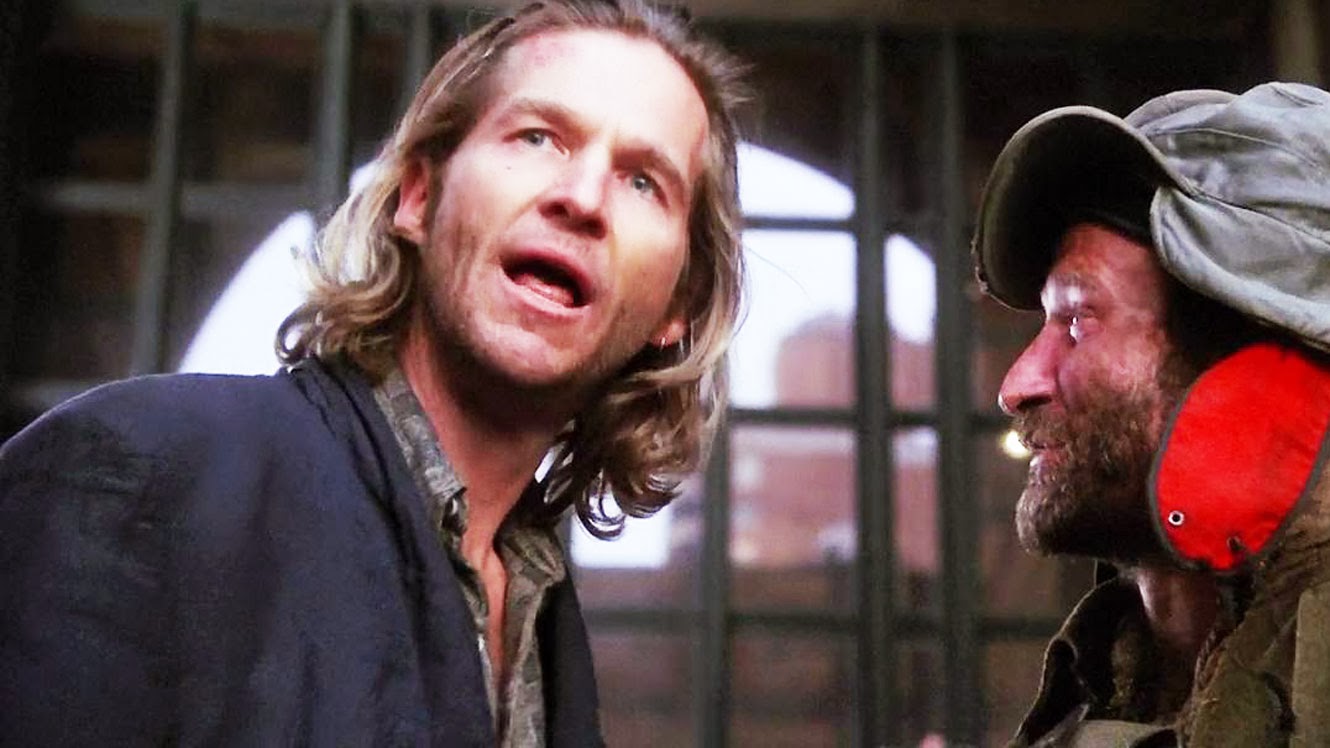

Jack Lucas’s (Jeff Bridges) star is on the rise. He has a hit radio show and is about to become a TV star when an unhinged individual takes his edgy, comically exaggerated rants too seriously and goes on a shooting rampage. 3 years later, Jack is a depressed alcoholic who only gets along thanks to the love and generosity of his no-nonsense girlfriend, Anne (Mercedes Ruehl, who steals the movie).

Jack crosses paths with Parry (Robin Williams) a homeless person whose wife was murdered at the shooting caused by Jack’s listener, years ago. Jack recognizes this as his chance for redemption and tries to help Parry get his life back on track. He starts by helping him court his dream girl, Lydia (Amanda Plummer).

Stylistically, Gilliam has a few opportunities to use his signature style. Parry’s hallucinations offer Gilliam brief chances to create a fantastical image of a fire-breathing, demonic knight. More interesting is how Gilliam turns mundane settings expressionist. Consider the set design in the opening scene, when the camera rises high above Jack’s radio booth, making it seem like a gray square alone in the universe, half ivory tower and half prison cell. Some of the supporting characters also fit the gallery of delusional misfits presented in some of Gilliam’s other works.

Gilliam followed up The Fisher King with 12 Monkeys and Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas which both became cult classics. However, since this successful trilogy Gilliam has yet to connect with audiences with as much success. These films, along with his classic Monty Python films and Brazil represent the moments when Gilliam’s unique point of view and surreal style connected best with audiences. As such, they are well worth examining and cherishing.

1. The Straight Story – David Lynch

The Straight Story is the small, touching, episodic story of an elderly man who rides his lawnmower out to make amends with his dying brother. It sounds more like an Alexander Payne movie, rather than one by David Lynch, the man behind moribund mutant babies and reverse-speaking dwarfs. Why would Lynch, known for his non-linear, dreamlike narratives, choose this very simple, very sane story as a project?

When 83-year-old Alvin Straight hears his brother, with whom he haven’t spoken in decades after a terrible fight, had a stroke, he decides he has to go see him. Too blind to drive and too proud to be driven, Alvin decides to make the 4-day journey from Iowa to Wisconsin on his lawnmower. On his way he meets a teenage runaway, bickering technician brothers, a woman who constantly, inadvertently hits deer with her car and many other kind people and characters.

These encounters prompt touching conversations about family, love and in one particularly gripping scene, harrowing memories from war. Straight’s journey and the characters he meets wouldn’t feel out of place in Twin Peaks. Amidst all of the conspiracies and mysteries, Twin Peaks, was also a fond portrait of quaint, off-beat small town USA and the people who inhabit it.

Lynch introduced us to a gallery of damaged, sadistic, violent characters in Blue Velvet, Lost Highway, Mulholland Drive and Twin Peaks. There is no doubt that Lynch believes that a warped mind can hide under any veneer and around any corner. These memorable creations make it easy to forget Lynch’s humanistic side, his empathy that made The Elephant Man so moving amidst all its cruelty, the empathy that infused Agent Cooper’s every breath.

The Straight Story feels so different because for once Lynch’s optimism seems to have overcome him. It is a film that believes in the possibility for forgiveness, hope, kindness and kinship. Perhaps this sentiment is made all the more convincing coming from a man who never hesitated to show us to the dark, twisted side of human experience.

Author Bio: Dean Movshovitz currently serves as Director of Film and Media at Israel’s Office for Cultural Affairs in North America. He has written for Tel Aviv Cinematque’s official film magazine, focusing on Israeli Cinema. Most recently, he wrote a web series analyzing Pixar Storytelling techniques. He is an aspiring screenwriter currently working on his fourth manuscript, a political thriller. Follow him on Twitter and check out his website.