11. The Proposition (2005) – John Hillcoat

While the United States and Mexico are two main settings for Western films, the Australian duo of John Hillcoat and Nick Cave decided to produce an amazing revision of the Western myth taking place thousands of miles from American soil. Telling the story of an Irish outlaw propositioned by the British government to capture his brother and bring him to trial for a mass murder is a perfect setup for a typical Western.

Instead of taking on the problem guns blazing, Hillcoat and Cave tell a laborious story not unlike Apocalypse Now (1979) where the outlaw Charlie Burns stalks his brother through the Australian outback while the British captain Stanley remains in town attempting to “civilize” the land.

Comparisons to Apocalypse Now and Joseph Conrad’s novella Heart of Darkness (1902) run rampant throughout the story. Images of empirical intervention in a new country, mistreatment of the native populace, the failure of governmental decisions who attempt to control something beyond control are all visible.

The film’s lengthy, ponderous shots allow the viewer to take in a newer landscape much like the Monument Valley of the Ford Westerns of old. The end result is a stunning revisionist Western set in a country with its own unique history in a predominantly American genre.

12. The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (2007) – Andrew Dominik

The title is a mouthful and the film is long and short on violence, but what unfolds in Andrew Dominik’s epic folk tale is a breathtaking noir-driven story about a real life legend who was equally mysterious as he was brutal and unpredictable.

However, most folk tales depict a romanticized version of the character in question, The Assassination of Jesse James… rather opts to tell two stories. While Jesse James is a primary focus of the story, the film itself is rather about James’ killer, Robert Ford. The only romanticization in the film is that of Ford’s, whose image of Jesse James far exceeds the real man. It is a rude awakening for him and the film juggles the two character’s relationships and hardships brilliantly.

Told in a minimalist fashion, the film’s troubled production yielded a fulfilling result. Choosing rather to tell of a tragic chronicle than an all-out Western outlaw shoot-em-up, The Assassination of Jesse James… is indeed an example of a new generation of Western cinema.

13. No Country for Old Men (2007) – Ethan Coen, Joel Coen

The Coen brothers returned from a cinematic slump with their highly-acclaimed No Country for Old Men. Adapted from Cormac McCarthy’s violent modern Western novel of the same name, the Coen Brothers tell an atypical contemporary story with Western roots. In it, three vastly different characters converge on each other in a messy confrontation that sees a high body count, all being a metaphor for fate and the path we all walk on this earth.

Set in 1980, the film does not fit the necessary criteria of a classic Western timeframe. However, the location of the film being set at the Texas-Mexico border (a site very familiar to McCarthy’s works) acts almost as a continuation of the violent history that particular area has seen for over 150 years.

Mexican drug dealers and covert assassins all make their presences known while working men and law enforcers attempt to make ends meet financially and psychologically in an inescapably violent world. Along with the Coen’s trademark bizarre dark sense of humor, No Country for Old Men serves itself as the ultimate contemporary Wester of its time.

14. There Will Be Blood (2007) – Paul Thomas Anderson

Three quasi-Westerns were released in 2007, and all three were discourses on many aspects of Western cinema and frontier history in itself. The final example of this is seen in Paul Thomas Anderson’s modern epic There Will Be Blood. Chronicling the story of prospector Daniel Plainview from 1898 to 1927, There Will Be Blood shows a descent into inhumanity.

Rather than focus on the gun-toting Western archetype, guns are seldom seen as tools of murder (with one notable exception). Instead, Anderson focuses on what makes up the greedy land barons seen so often in Western films. Daniel Plainview is an anti-hero, willing to destroy anything that will turn a profit for him. He also fights the laws of the land, specifically the religious moral right in the form of the young charismatic preacher Eli Sunday.

The film is not even about land grabbing and prospecting. It is rather about oil and its (at the time) innovation and industrial clout in a budding American economy. Not only does Anderson use a Western trope to tell his story, but he uses an old tale to mirror a sense of greed and horror that has followed history up to our current times, much like the sprawling epics of Howard Hawks and John Huston, There Will Be Blood uses minimal Western tropes to tell a meaningful Western story.

15. The Good, the Bad and the Weird (2008) – Kim Jee-woon

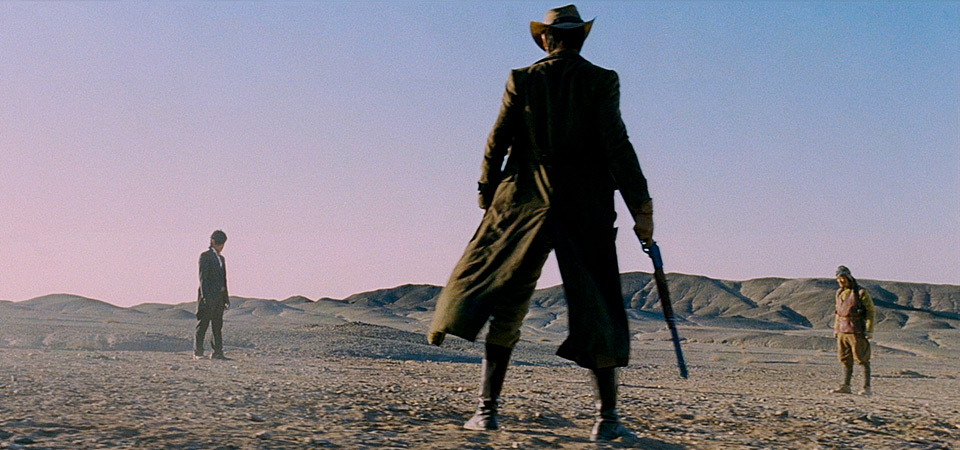

Closing the list is an infusion of almost every other film mentioned on this list. Kim Jee-woon’s “Eastern Spaghetti Western” is pretty much an Asian re-telling of Sergio Leone’s The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, but with a distinct and unique approach that sets it aside from its original.

The Western’s relation to Eastern culture and cinema has been both inspirational to and inspired by each other. Akira Kurosawa wished his samurai films to be shot as John Ford would have shot them, Sergio Leone borrowed from Kurosawa who was borrowing from Dashiell Hammett and helped form the Spaghetti Western genre. Kung fu cinema set the framework for various Westerns and Hollywood filmmakers like John Sturges Westernized Japanese samurai films like The Seven Samurai (1954) in their own classical sense.

The Good, the Bad and the Weird, being a South Korean film, is rooted in the country’s own history. Despite having certain characters riding around on horses and wearing dusters and cowboy hats, there are obvious references to the Korean-Chinese-Japanese ordeals in Manchuria, which set the entire story in motion, there are lone gunmen with possible past histories as bloodthirsty outlaws masquerading as incompetents, and in the end, oil production is a final plot point to drive the film’s message home. It is all told as far away from the American West as possible, but it plays out and is a direct homage to the American and Spaghetti Western.

Added on to the overall Western themes, The Good, the Bad and the Weird also splices in Korea’s distinct style and cultural imagery as well. The propensity for stylized and gritty violence dominates the film’s action, allowing director Kim Jee-woon to dub his film as a “Kimchee Western” due to the spiciness and vibrancy of the Korean culture and people.

The Good, the Bad and the Weird is a perfect ending to this compilation of Westerns that argue the myths and rules of typical Western cinema, but it also opens up whole new worlds of what possible Westerns could come to be in the future.

Author Bio: Josh Schasny is a film studies graduate and screenwriter based out of Montreal, Quebec. A born film buff he loves to get together with people to talk film. He also writes lists, articles, scripts, helps people shoot films, and one day will eventually die.