6. Night of the Living Dead (1968, USA)

George A Romero’s debut almost single-handedly defined the modern zombie. It’s easily forgotten, but before the zombie apocalypse was devoured by popular culture, Romero used it to comment on the changing socio-political landscape of Cold War-era America.

A group of seven strangers become stranded in a remote farmhouse which comes under the attack of a growing hoard of mindless, reanimated corpses who feast on the living.

‘Night of the Living Dead’ evokes fear not merely in death but decimation. Composed in a time when the end of the world seemed a real possibility, it draws upon several of the political discourses of the 1950s- 60s. These include: the civil rights movement, the Vietnam War, the women’s liberation movement, calls for nuclear disarmament and the decline of the Kennedy dynasty. Instead of focusing on any one of these concerns, Romero combines them all into one claustrophobic nightmare.

Above all, the film critiques authority and the way it makes monsters of the every man. The army of undead, the epitome of conformity, could be seen as an allegory for the US army turning soldiers into brainless, killing machines.

Living villains also exist; Romero contrasts the patriarchy of the nuclear family, embodied in Harry’s attempt to assume control, with a world which is falling apart. The conclusion, showing Ben, the only black character, shot and burned, recalls the assassinations of civil right activists including Martin Luther King and Malcom X.

‘Night of the Living Dead’, one of the first modern horror films, serves as a snapshot of a traditional America whose day has come to a close. Romero in his next film, ‘Dawn of the Dead’, would offer a critique of the consumerist society that took its place.

7. The Wicker Man (1973, UK)

‘The Wicker Man’, directed by Robin Hardy, is an essentially British film. Replacing violence for eroticism, folk music and a devastating twist ending, the film warns of the danger of confronting Catholicism with Paganism, both at the heart of the nation’s identity.

The devout-Catholic Sergeant Howie (Edward Woodward) visits an isolated island, governed by the pagan Lord Summerisle (Christopher Lee), in search of a missing girl. Immediately the film is characterised by conflict; the film’s opening, contrasting Howie’s plane with the rugged Scottish landscape, forewarns a clash of two worlds.

‘The Wicker Man’ depicts a nation trapped between tradition and modernity, old and new. The emergence of class consciousness, counter-culture, and the New Age movement of the 1970s (which rejuvenated Celtic beliefs), came to challenge the Anglo-Saxon identity.

Unusual for a horror movie, ‘The Wicker Man’ takes place mostly during the day. It places practices supposedly from the Dark Age – public orgy, phallocentrism and human sacrifice- in an apparently enlightened time. Whilst Paganism is deliberately presented as absurd, it is shown to be somehow keeping society intact. Once more, there are undeniable similarities between the ‘polar opposites’ of Paganism and Catholicism. What’s more bizarre; worshipping sex or renouncing it? Burning people alive for apples or burning people alive because they’re ‘witches’?

The chilling ending, split violently between Howie signing Psalm 23 and the villagers’ reincarnation of the poem “Sumer Is Icumen In”, accentuates the danger of weighing the British identity on either of these religions.

The failure of the US remake further cements ‘The Wicker Man’ as the quintessential British horror film. It’s uniquely British perspective of religion remains to be seen in later classics such as Ben Wheatley’s ‘Kill List’

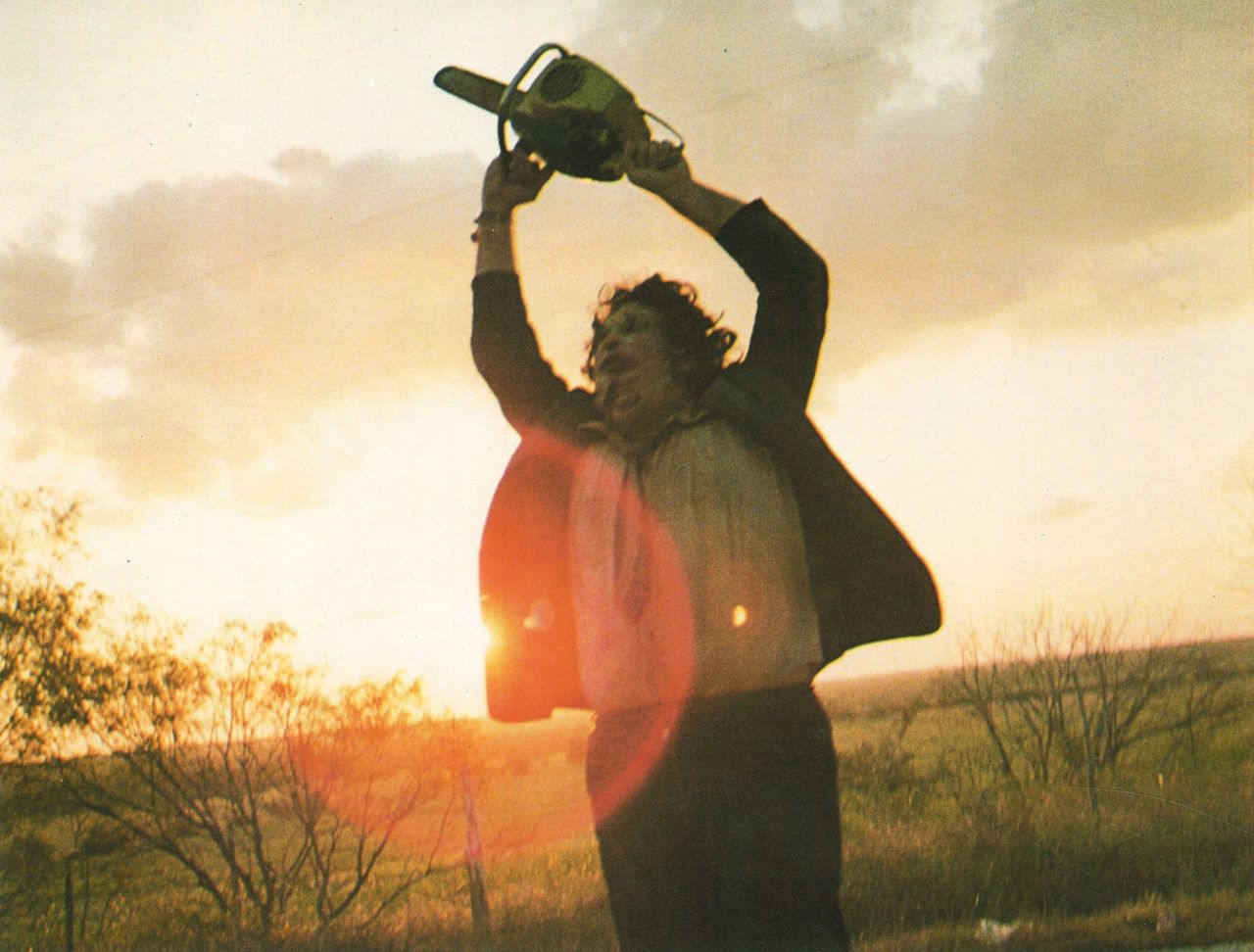

8. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974, USA)

Tobe Hooper’s landmark debut remains one of the most terrifying films ever made. Part of the film’s success comes from its unflinching look at the dark heart of capitalism which most would rather ignore.

Five friends on an afternoon drive unwittingly fall victim to a patriarchal clan of cannibals. Slaughter is foreshadowed from the very beginning; silent contrasts between their Scooby Doo Mystery Machine-like van and a cattle-yard are arguably the most unnerving frames of the film.

The fear is not merely murder, but murder which is industrialised and commodified. The US’s prolonged involvement in the Vietnam War catalysed a movement of counterculture with focused concern on the fate of the new generation.

As the opening exposition implies, the film’s distinctly hippyish teenagers were killed simply because “they were young”. Hooper compares the raising of the new generation to the practice of breeding animals solely for slaughter, either for food or for leather clothing and decoration.

The film can be interpreted as a critique of the Vietnam War, the patriarchal nuclear family, consumerist obsession with fashion and body image, the meat industry, or even the oil crisis of 1973, considering it is the Proprietor’s empty gas pumps which initially get the kids into the mess.

The film remains disturbing because it gives the implication that murder, regardless of intent or morality, is necessary. What are these men, lost in an economic boom, to do but catch people and eat them? The Sawyer house is metaphoric for America itself: outside are daffodils and a white picket fence providing the American Dream, but inside are grisly relics of the killing needed to sustain capitalism.

The horror is that we’re all guilty in some way or another.

9. Suspiria (1977, Italy)

Dario Argento’s ‘Suspiria’ is an experiential film famed for its resemblance to a nightmare. Whilst most of the praise goes to its cinematography, soundtrack, and use of colour, it’s worthwhile considering the film as a cultural artefact.

American ballet student Suzy Bannion (Jessica Harper) comes to discover the dark forces controlling the West German dance academy in which she is newly-enrolled. Between are a series of spectacularly violent yet strangely hypnotic murders.

‘Suspiria’ evokes fear not in evil itself but rather man’s incapability to comprehend it. Post-war Italy was haunted by the legacy of Mussolini, the founder of fascism, and the Republic of Salò, which essentially acted as a puppet state to the Third Reich.

The film does not occupy a space of intellectual thought. Rather, Argento’s stylized combination of bizarre set designs and an overheavy score by prog-rock band Goblin, suggest a world dominated by terror and confusion. The misinformed climate of the totalitarian state is compared with the innocent worlds of fairy tales.

The lullaby-like score, pans through the black forest, maggots falling from the ceiling, and the academy painted arterial red, recall the innocent settings of the Brothers Grimm. In contrast, the murders carried out by the coven of witches perhaps are allegorical of the brutal acts needed to secure the fascist regime.

‘Suspiria’ is scary because it indulges in childhood fears and historical guilt; it reminds that monsters do indeed exist. They’re simply posing in human skin.

10. Cronos (1993, Mexico)

The vampire fable ‘Cronos’ launched Guillermo del Toro’s career and remains one of his finest achievements. On one hand, a product of Latin American magical realism, and on the other, a social commentary of US-Mexico relations, the film warns of the consequences of dollar imperialism.

An elderly antique dealer Jesús Gris (Federico Luppi) discovers ‘the Cronos device’: a tool to providing eternal life sought by a dying American industrialist (Claudio Brook) and his nephew Angel (Ron Perlman).

Del Toro assures that capitalism remains a degrading influence on Mexican culture. ‘Cronos’ was made in anticipation of the North American Free Trade Agreement, feared to open the domestic economy to a competitive foreign market.

Del Toro replaces the ‘Monroe Doctrine’, which posits that the US owns paternity over the Americas, with his own gothic mythology. Its religious themes – namely the biblical comparisons of the aptly-named Jesús to the resurrection of Christ – recall the magic realism which emerged in Latin America in the 1960s-70s in response to political instability.

But is Jesús really a vampire? The industrialist, the embodiment of US greed, shrivelling and dying, is the real blood-sucker of the film. The Cronos device, made in the 16th century and laced in gold, is representative of the nation’s wealth sought first by the Spanish Conquistadors and now by the United States. Other allusions may be recognised; namely Jesús’s addiction to the device, reaching a kind of ‘high’ when it injects him, comments on Mexico’s increasingly violent drug war.

Unusually del Toro sympathises with the monster, raising him to an almost pious stance. In contrast he dismisses the commodified lifestyle of the West as a foreign, unwanted entity.