11. Suicide Club (2002, Japan)

A highly-polarising film, Sion Sono’s ‘Suicide Club’ has gained a strong cult following. Controversial for its graphic violence and for its taboo-breaking subject, the film uncovers several fears of modern-day Japan: conformity, the influence of popular culture, and a growing divide between young and old.

In the film, the Tokyo police attempt to establish a link between a string of horrific suicides. The opening, showing 54 schoolgirls jumping in front of an incoming train, is grotesque, intriguing, and as the cheery music suggests: ironic.

Bookended by footage of a fictional pop band, ‘Suicide Club’ offers a pitch-black satire of Japan’s obsession with popular culture. The film responds largely to the emergence of the J-pop genre in the 1990s.

In one of the more memorable scenes, a group of students hear about the mass-suicide at the railway station and decide to jump off a building, like it were a fad. In another, specifically resembling a music video, an anonymous man, dressed like a glam-rock singer, looks directly at the camera and performs a song while a girl is raped and murdered.

At its most basic, the film taps into fears that cultural and individual identity has been lost. Suicide rates significantly increased in Japan during the 1990s, and suicide, especially on the grounds as a mental health issue, remains a taboo subject. The ritualization of suicide in the film, comparing it firstly to the mechanical nature of a train schedule, recalls the traditions of seppuku. Life and death have been placed on a routine.

Those who manage to finish ‘Suicide Club’ will be rewarded a disturbing look into the cultural fears of an industrialised nation. Whatever one’s opinion, it’s unlikely to be forgotten anytime soon.

12. Wolf Creek (2005, Australia)

It goes without saying that Greg McLean’s slasher-cum-torture porn ‘Wolf Creek’ is a controversial movie. It accentuates the hostility of an indifferent landscape and exposes the patriarchal tones found at Australia’s heart.

Constructed with the promise of a true story, ‘Wolf Creek’ sees a group of young tourists become stranded in a remote part of the Western Australian outback where they fall victim to the psychopath Mick Tayler (John Jarratt).

The idea that Australian society, an object of British imperialism, is trespassing on the bush is a colonial fear and a core aspect of the Australian New Wave. The bush is a living entity which will consume the white tourists which have entered it.

‘Wolf Creek’ gives the suggestion that nature makes monsters. Mick Taylor is a satire of the masculine stockman archetype which dominated the Australian screen in the 1970s and 1980s. His transition from helpful hunter to serial killer who tortures women for sport, forces one to consider the patriarchy at the heart of a nation’s identity.

The final lingering frames – a silhouette of Taylor waltzing and dissolving into the sunset – subvert the traditional happy ending. We’re left to despair that the true enemy is not a single man, but rather an intangible idea which has become disfigured and deranged.

‘Wolf Creek’ is a quintessential Australian horror film. McLean would later turn his attention to Australian hostility towards asylum-seekers in the sequel ‘Wolf Creek 2’, focusing on the hypocrisy of racism in a multicultural nation.

13. The Host (2006, South Korea)

Bong Joon-ho’s tragicomedy ‘The Host’ has been hailed as one of the greatest monster movies of all time. Coming from a nation established by the US; the film offers insight into South Korean fears of submissiveness in regard to American influence.

Park Gang-du (Song Kang-ho) and his family attempt to save his daughter after she is captured by an amphibious, carnivorous creature. Joon-ho wastes no time in revealing his intentions; the first scene shows an American pathologist in a grimy military operating room commanding his Korean servant to dump poisonous formaldehyde. This act of American negligence presumably gives rise to the monster.

The current relationship between America and South Korea is unbalanced. The prologue parodies a real incident in 2000 when formaldehyde was dumped by a Korean working with the U.S. Military. Other direct references are made: the biological weapon “Agent Yellow” is comparable to Agent Orange, while the fabricated myth of the virus recalls the US’s excuses to enter the Korean War among other world conflicts.

Whilst the film accepts many of the conventions of the Cold War monster movie, where the US’s carelessness in nuclear testing resulted in the creation of monsters, it abandons many of its escapist elements.

In situations where we would expect some form of deus ex machina – a random action which could save someone from the monster or allow a dead person to be resurrected – no such action occurs. In the end a homeless man is more useful in solving the national crisis than the US army and the Korean government combined.

As it is revealed, the monster is not “The Host” that the film’s title refers too. South Korea itself is the host; the virus is American imperialism.

14. A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night (2014, USA/Iran)

Ana Lily Amirpour’s vampire western offers a unique perspective. Whilst shot in California, it is filmed in Persian and evokes cultural fears distinctive of the Middle East.

A romance set in an Iranian ghost town ‘Bad City’, the films follows Arash (Arash Marandi) who meets an unnamed vampire (Sheila Vand). The film, set between nations and centuries, celebrates identity. Several influences may be noted: the Anamorphic monochrome cinematography recalls the elongated panels of graphic novels, the soundtrack includes Iranian and American songs, and the editing, often cut to the rhythm of the Morricone-like music, resembles a spaghetti western.

Regardless however, the Iranian backdrop prevails. Its poetic retelling of the everyday lives of the lower class recalls many of the larger themes of the Iranian New Wave. There are frequent reminders of industrialism; Amirpour’s strangely unsettling departures to observe punkjacks rocking in the distance present the oil industry itself as vampiric.

As implied by the title, the true concern of ‘A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night’ is the victimisation of women. The movie positions the female as an unnamed other: a lonely, nocturnal creature who hunts evil men. At its most creepy the film watches her follow a victim silently in the distance with a chador leaving only her face exposed. The fear is that women have become a monster in the eyes of society.

‘A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night’ is a vampire romance which thankfully diverts from the post-Myer teen love story, more closely resembling Tomas Alfredson’s ‘Let The Right One In’ and Kathryn Bigelow’s ‘Near Dark’. It serves as a cultural mash-up which is fun, thought-provoking, and creepy.

15. It Follows (2015, USA)

Although David Robert Mitchell’s ‘It Follows’ provokes existential dread, and occupies a space reminiscent of John Carpenter and David Cronenberg, the film ultimately is a contemporary tale.

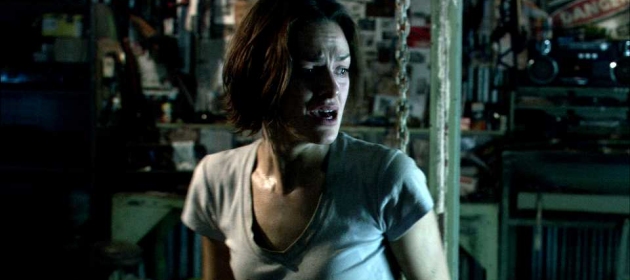

Jay (Maika Monroe) is a young woman who ‘contracts’ a curse after having sex with her boyfriend (Jake Weary), meaning she’ll be followed by a supernatural entity until she can pass it onto another. The lengthy first shot, showing a calm, upper-middle class suburbia fractured by a girl fleeing for an unknown reason, asserts that this a horror story about regular people in a regular place.

It provokes a terrifying thought: there is a pervasive and destructive force found even in the apparent safety of the neighbourhood. On many layers the film works as a response to the Sexual Revolution in the western world during the 1960s. Fear of intimacy may be primordial; however nowadays it refers to an all too real enemy: sexually-transmitted disease which cannot be detected nor cured.

In spite of this, ‘It Follows’ is not a puritanical film. The certainty of death is weighed with the dangers of sex. Exerts from Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s ‘The Idiot’ and T.S. Elliot’s ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock’ are read aloud and one of the earliest forms the creature takes is an elderly woman.

Death follows. Love and sex are presented as methods by which we may defer death; the film’s final tracking shots suggest Jay and her new boyfriend Paul have accepted the shortness of their time on earth, and would spend it together rather than running.

‘It Follows’ resonates because it places humanity’s deepest fears: intimacy and inevitable demise, in an all too familiar setting.

Author Bio: Kyle McDonnell is an aspiring filmmaker based in Sydney, Australia. He recently graduated from high school and hopes one day to emulate his screen heroes David Lynch and Ben Wheatley. When he’s not watching, writing or filming, he can be found listening to ‘The Smiths’, contemplating life.