Economically at least, Europe has been going through something of a dark period lately. It is arguable whether this economic gloom has caused European cinema in turn to produce increasingly bleak and hopeless films.

Throughout its long history, European cinema has never shied away from despair. The German Expressionists used every technique at their disposal to illustrate the darker recesses of human psychology. The neorealists looked unflinchingly at post-war poverty. Pasolini was unrelenting in his exploration of humanity’s sadistic potential.

Ingmar Bergman was a one-man juggernaut of existential dread. So, whether the apparent hunger in European arthouses for darkness is anything new is debatable. Whatever the case may be, the list below hopefully proves that the current stars of European cinema have done an excellent job in continuing Europe’s lasting affair with the dark.

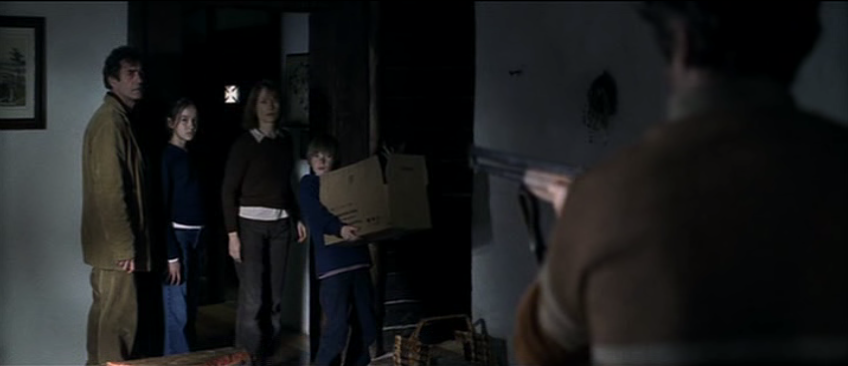

1. Time of the Wolf (Michael Haneke, 2003)

Time of The Wolf is extremely dark in both senses of the word. It is set in what seems to be a post-apocalyptic Europe, though no explanation of the circumstances is provided.

Isabelle Huppert arrives home with her family, only to find the house occupied by armed strangers. She is forced to flee, though we’re never sure where. Electricity is gone, so when the night comes round, the screen is often almost completely black. This makes for an entirely unnerving experience, eliciting that sense of total dread for which Haneke is famed.

Time of The Wolf may not be as outrageous as Funny Games, or as politically pointed as The White Ribbon and Hidden, but as a vivid evocation of sheer doom it is every bit an artistic success as the Austrian director’s more famous films.

2. The White Ribbon (Michael Haneke, 2009)

The White Ribbon was haled by some as Haneke’s most mature film to date. Gone were the strategic outbursts of extreme violence that many saw as cheap shock tactics. Still, the director’s currently unparalleled talent for creating and sustaining an overwhelming atmosphere of dread still dominates.

Indeed, The White Ribbon is comparable to Hidden, in how it takes the form of a ‘whodunit’ without providing the solace of a resolution. But it is the film’s entirely believable reconstruction of a small German town on the edge of the nazi era that impresses the most. And Haneke’s aforementioned knack for creating a mood of generalised dread is perfectly suited to the depiction of a community on a slow descent into barbarity.

3. Dogtooth (Yorgos Lanthimos, 2009)

Upon release, Dogtooth was heralded as a modern European masterpiece, and its previously obscure director, Yorgos Lanthimos, was quickly compared to directors such as Von Trier and Haneke for his bleak and idiosyncratic vision. Winning the Un Certain Regard prize at Cannes, and getting a nomination for the Best Foerign Language Oscar sealed the film’s international success.

The film offers a morbid take on the idea of home schooling. A married couple keep their children locked inside a large compound (with a garden and pool); they have never seen the outside world. Their education is unusual to say the least: the film opens with a language lesson, where everyday words have entirely unexpected meanings.

Roger Ebert described Dogtooth as a car crash film, one from which you cannot look away, despite the horror of what is occurring. The unusually beautiful and serene cinematography adds to this paradoxical watchability.

4. Import/Export (Ulrich Seidl, 2007)

Austrian director Ulrich Seidl had already made something of a name for himself with Dog Days. He has continued to stir controversy ever since, with some condemning him as an exploitative misanthrope, and others praising his fearless depiction of society’s (and cinema’s) undesirables: the obese, the ugly, the dull, the dying.

Import/Export has more obvious political reach than Seidl’s other films. The title refers to the film’s bifurcated structure: half of the film focuses on Olga, a Ukrainian single mother failing to survive on wages as a nurse and internet cam girl. She moves to Vienna where she works first as a housekeeper for a rich family, then as nurse in a home for the elderly.

The second half of the film focuses on Pauli, a young man from Vienna. Pauli is taken on a work trip to Ukraine by his stepfather Michael, where they’re supposed to set up arcade gambling machines.

Michael evidently wants to make the trip an opportunity to bond, but his efforts are a little grotesque: much of their time together sees the older man trying to get a prostitute for his unenthusiastic stepson. If both parts of the film separately seem like dead ends, they come together to form an intensely sad and sometimes bitterly comic picture of the divide between eastern and western Europe.

5. Songs From The Second Floor (Roy Andersson, 2000)

Roy Andersson has spent much of his film-making career making commercials rather than films. Despite the fact that his more famous films are nothing like adverts in tone, their unusual structure does seem to hint at the influence of commercial work. Songs From The Second Floor does not have a discernible plot, rather it is a series of increasingly bizarre and deadpan vignettes, set in a terminally grey parody of a typical Swedish city.

While the film is clearly a comedy, much of the humor cuts so close to the bone that one is more likely to wince than laugh. It never just feels like an extended sketch-show, however. Andersson’s mastery of tone, and careful management of recurring themes and images ensures that the film feels coherent despite the disordered surface.

6. You The Living (Roy Andersson, 2007)

You The Living is very much a companion piece to Songs From The Second Floor. The setting seems to be the same grey and gloomy Scandanavian city with similarly sallow and morbidly depressed inhabitants. The structure too is the same: bitterly comic vignettes causing more discomfort than laughter, mundane scenarios punctuated by occasionally spectacular bursts of surrealism (one such scene features one of cinema’s strangest and greatest guitar solos).

You The Living is, by a pinch, a little lighter in tone than its predecessor, with less of that film’s somewhat sadistic play with pacing, and as such it works as the perfect introduction to Andersson’s oeuvre.

7. Outside Satan (Bruno Dumont, 2011)

Bruno Dumont made his first splash on the international scene with The Life of Jesus, which offered an uncompromisingly harsh view of small-town life in the director’s native Belgium. Dumont’s films have continued to be relentlessly dark affairs: his cinema is characterised by aspects of New French Extremity and Contemplative Cinema, and Outside Satan is no exception.

Long, slow and carefully framed shots of sparse scenery, very little dialogue, explicit sex featuring bodies that would never be seen anywhere near Hollywood, and casual bursts of severe brutality, these are some of the elements that make the typical Dumont movie. Outside Satan, as the title suggests, adds some obscure metaphysics to the mix, and, unsurprisingly, considerations of Evil sit well within Dumont’s violent aesthetic.

8. Twentynine Palms (Bruno Dumont, 2003)

Twentynine Palms saw Dumont refining the uncompromising aesthetic he’d become known and taking it in less familiar direction. Where his previous films had focused on small towns and their slightly grotesque inhabitants, this film features an attractive couple traveling by car through the Southern Californian desert.

It’s a slow and beautifully shot meditation on love, sex and violence. While some viewers have found most of the film a little too slow, the ending never fails to leave viewers reeling from shock.

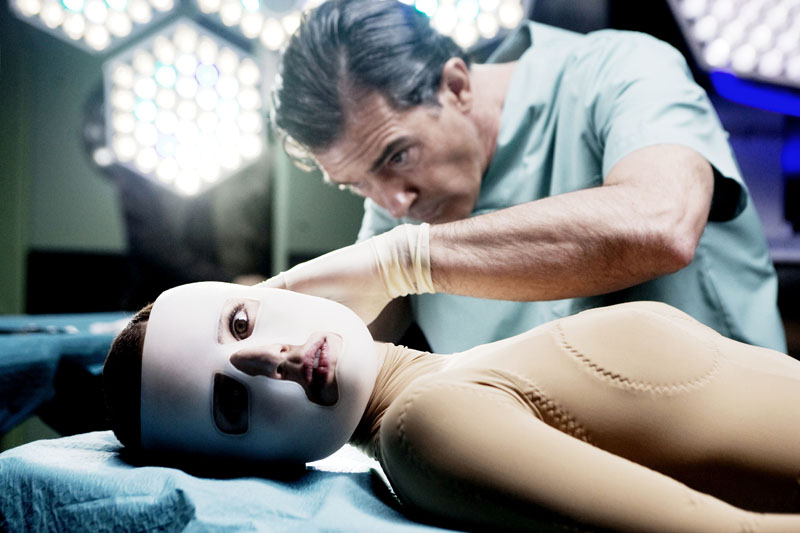

9. The Skin I Live In (Pedro Almodovar, 2011)

Pedro Almodovar has always had dark subject matter at the heart of his films, though these topics are often tempered by the human warmth that pervades his ensemble casts. The Skin I Live In is certainly Almodovar’s darkest film of the past decade, which is unsurprising, since it’s the director’s most explicit effort to make a horror film to date.

Antonio Banderas plays Doctor Robert Ledgard, who is working on a way to make human skin more resistant to aging. Officially, he uses mice for his experiments, but in fact, in his secluded mansion, Ledgard keeps a human subject, Vera, captive. Almodovar has always had a flair for pastiche, and this film is no different: elements of everything from the original Frankenstein films, to classic Hitchcock are evident. But as usual, the elements of pastiche are just part of wide, wild canvas.

10. Antichrist (Lars Von Trier, 2009)

Lars Von Trier has an unusual difficulty: with each new film, it seems that he needs to find a new way to cause outrage. Antichrist was a successful continuation of that trajectory, in that it proved a smash hit of notoriety, the kind of film that people talked about without seeing it.

Willem Defoe and Charlotte Gainsbourg play a couple who have recently lost their only child in a tragic accident. When they retreat to a secluded cabin in the woods, they are both overcome by increasingly dark psychological disturbances. Antichrist is the first film in Von Trier’s so-called “depression” trilogy: films that arose from the director’s own experiences with depression.