10. Japanese Summer: Double Suicide (Japan, 1967)

Oshima Nagisa has always confronted the claims of some that anarchism is a wholly European invention (despite the fact that much of the earliest Taoist thought is anarchal).

In this absurdist “outcast” film, Oshima depicts two alienated youth—the audaciously erotic Nejiko and contemplative death-obsessed Otoko—hiking outside Tokyo. They are captured by a band of anarchists, who have holed up in anticipation of enacting their plans. However, a “lone wolf” American gunman has preempted them with his own violent outburts.

Eventually, Nejiko and Otoko join the American in his battle against the police. As the trailer announces: “Revolution or war? Every conceivable weapon on hand, liberation or destruction? the urge to kill grows stronger. Guns—rifles daggers—swords The signature themes of sex and violence A whirlwind of eroticism explored once again by Oshima, heating up the long hot summer of 1967 with this audacious drama.”

9. Alexander the Great (Greece, 1980)

An open critique of private property and institutions of social, sexual, and gendered control and coercion, Theo Angelopoulos’s challenging address of the myth of the Macedonian king is simultaneously a stylized redeployment of the conqueror’s life and a critique of the figure it deploys. This complex dualism makes the film difficult to appreciate and explains its poor critical and public reception.

Set in 1899, the film give us an Alexander who is a revolutionary, an outlaw, and an anarchist struggling against the monarchy as well as the local villagers who have staged their own non-violnet coup and denonced hierarchical social arrangements.

Rather than side with the people, who know what they want, though, Alexander betrays them to the Monarch, who later betray him. In the end, Alexander is deposed by the village women, who transmogrify him into a marble statue that serves as a cautionary reminder rather than a celebratory memorial.

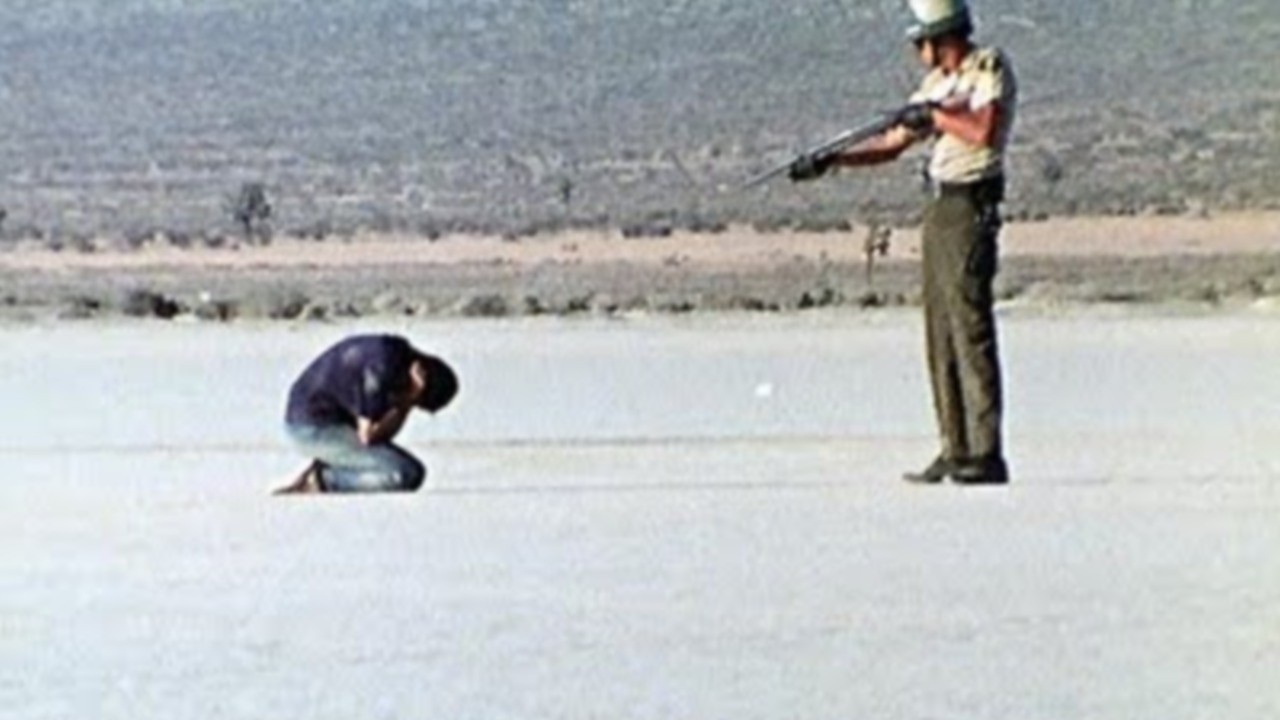

8. Punishment Park (USA, 1971)

When the state serves as the guarantor of free speech, human rights, and social justice, the game is rigged from the onset. Thus, what is needed is a structural challenge to the success of the system. Written and directed by Peter Watkins and produced by Susan Martin, Punishment Park is a pseudo-documentary that makes this point and emphasizes it without apology.

Featuring amateur actors and shot with hand-held cameras, the film’s confrontational approach provokes a visceral reaction as it stages arrests, tribunals, debates, and the murderous “game” at its center.

In this dystopic version of the 1970s, under title 2 of the Internal Security Act (passed by Congress in 1950 and most recently invoked against Chelsea Manning in 2010), President Nixon has consolidated all domestic governmental authority within the executive branch and instructed the police and military to detain and punish any and all dissent.

Dissident trials are foregone conclusions, and afterwards they are given the choice of long prison terms or the opportunity of gaining their freedom by surviving the guantlet of running fifty-six miles through the desert while being hunted by police and national guard troops.

The film crosscuts between one group attempting to traverse the “park” and one group still on trial. In this way, the film illustrates the theories of the testimonies through images of the practices of the dissidents “in the field.” From the start, we know the authorities will always win, not because of individuals, though, but because the maintenance of the institutions is paramount.

The roughness and direct address of issues of race, class, gender, and imperialism mark Punishment Park as an extremely valuable relentless, didactic composition. This film is a raw version of The Hunger Games, without the fairytale disguise.

7. Eros + Massacre (Japan, 1969)

Directed and written (with Masahiro Yamada) by Yoshihige Yoshida, this Modernist biopic of the early twentieth-century anarchist Sakae Ōsugi (Toshiyuki Hosokawa), might instead be called “Past + Present” for its sometimes abrubt transitions, rhythmic jumpcutting, and counter-chronological narrative devices.

In this dialogic (often surrealist) film, Eiko and Wada are students researching the sexual and social politics of 1920s Japan, when characters from this period begin appearing and acting in the contemporary world. In the end, a director hangs himself with film, and the other characters are preserved in a group photograph.

Praised as perhaps the most important film of the Japanese New Wave, it confronts modern industrial political issues through a complicated allegory of the relations among the cinema, desire, corporeality, erotics, history, memory, and social violence.

6. Libertarias (Spain/Italy/Belgium, 1996)

Barcelona. 1936. The Spanish Civil War. Four women join in the fight against the Nationalist government and right-wing elements of the Church. Pilar is a militant feminist. Floren is her comrade in arms. Charo is a sex worker radicalized by the war and her recognition of the gender and sexuality inequalities that permeate the social structure.

María is a nun whose convent is overtaken by anarchist revolutionaries, forcing her into the company of the other women. Once among these Free Women, María begins to challenge Church hypocrisy as well as her own innocent, sheltered life to that point. Although she refuses to pick up a gun, she does learn to see the injustice and violence surrounding her.

The women express desires to confront the totalitarian institutions and serve on the front lines—as fighters or supporters—but other women and men attempt to dissuade them. They are told women should work in factories and cook behind the lines while the men soldier on.

After an initial victory, patriarchal and fascist forces reassert themselves, and the women are betrayed by the allies they had grown to believe in. This film has been recognized for its special focus on the important role women played in the war against fascism and the previous denial of their full recognition.

5. Land and Freedom (UK/Spain/Germany/Italy, 1995)

Perhaps the best feature film about the Spanish Civil War, Land and Freedom was directed by Ken Loach, written by Jim Allen, and produced by Rebecca O’Brien. The film is revealed in flashback through the eyes of the main character’s granddaughter, who has discovered his wartime letters.

The focus is on David Carr (Ian Hart), an unemployed worker and member of the Communist Party of Great Britian, who joins the fight against the Fascists. In some ways, the film is a standard war movie, concentrating on the stuggles of a central character within a small band of fighters. Our sympathies are always with these fighters, even after the hero is wounded and leaves to recover and eventually joins a military cadre aligned with the government.

These unites are hierarchical, with imposed ranks and divisions of labor and gender. Disillusioned with the official units, Carr returns to the anarchist brigade—where men and women fight side by side and elect their own leaders when necessary.

Later, when the brigade clashes with government forces, several fighters—including Blanca, with whom Carr has fallen in love—are killed, and the anarchists are forced to surrener. Carr returns to England with a handful of Spanish soil. Land and Freedom won the FIPRESCI International Critics Prize and the Prise of the Ecumenical Jury at the 1995 Cannes film festival.

4. Matewan (USA, 1987)

Written and directed by John Sayles, Matewan is an ambivalent union film that stages a reenactment of the 1920 coal miner’s strike in Matewan, West Virginia, including the final gunfight between the townspeople and the anti-union thugs that left seven people dead. It falls squarely into Sayles’ style combining history, biography, and social consciousness.

As the miners in a company town begin to organize for better working and living conditions, the company attempts to replace them with Black and Italian-immigrant scabs. When he sees the company’s plan to foment conflict between the groups of workers, organizer Joe Kenehan (Chris Cooper) convinces the townspeople and the new workers to unite agianst a common foe.

Tensions escalate as the company employs union busters against those who have organized, and these enforcers evict, injure, and kill several resisters. After the showdown between the forces, the film ends with an epilogue recounting how the violence continued to plague local social relations for years.

The film depicts the complex, dynamic intersections among race, class, ethinicity, and gender involved in twentieth-century labor organizing. While it clearly stands for the miners and townspeople—including the local police and politicians—against the company and the hired guns they employ, its ending—with the labor organizer sparking the violence he sought to avoid—leaves open questions regarding unions as the best possible solution to the exploitation of workers.

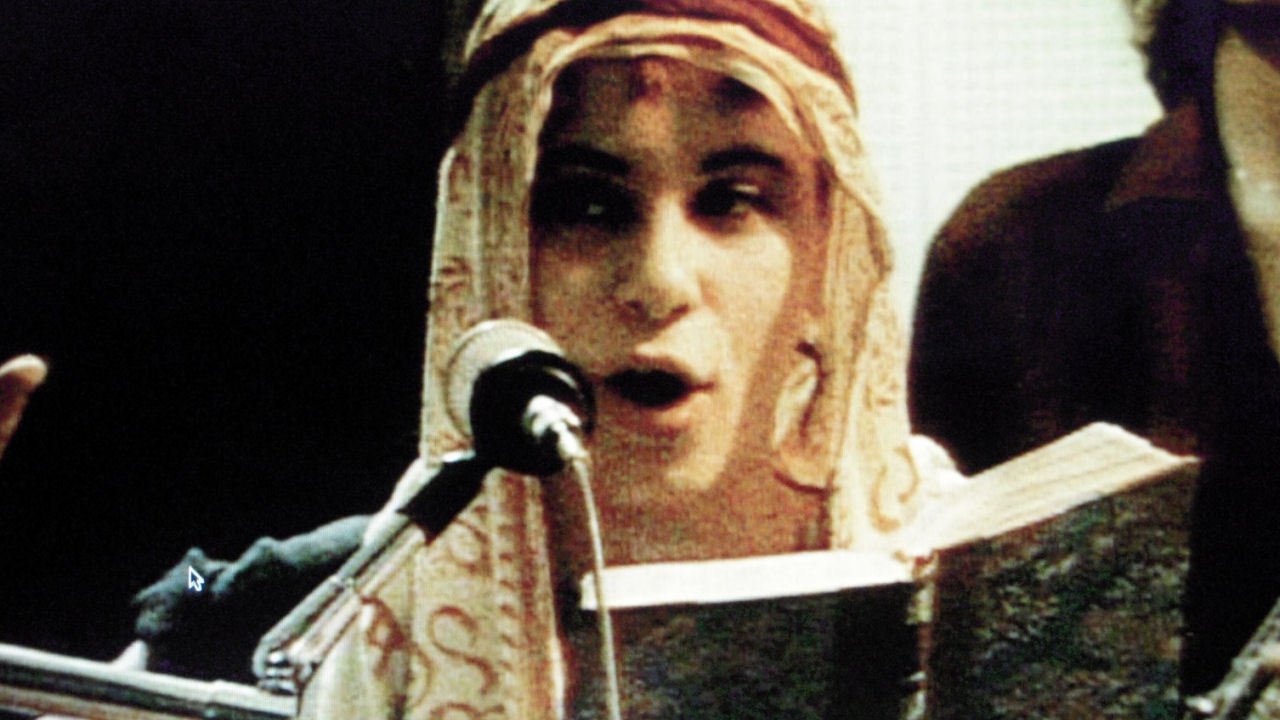

3. Born in Flames (USA, 1983)

The one example of feminist, queer, science fiction on this list, Lizzie Borden’s film takes a “documentary-style” approach in presenting its futuristic image of America reborn as a socialist democracy pushed toward anarchist activation by women’s pirate radio.

In New York City, ten years after the peaceful socialist revolution, two feminist radio stations—one led by a white lesbian and one led by a soft-spoken black woman—give voice to the shortcomings of the revolution, which some argue has led to a dystopian system of governmental control and aggrevated patriarchal abuse.

After a prominent feminist is detained and dies in custody, three investigative journalists are fired for their coverage of FBI agents, and both radio stations are burned down, the radio groups unite and join with the Women’s Army in direct actions against the authorities.

Eventually, a group of these activists mobilize against a speech by the President of the United States, urging reforms to the system. They demand the right for self-rule from the elites and blow up the radio tower atop the World Trade Center to end all future hegemonic media messaging. The film emphasizes alternative aesthetics, direct (rather than representative) democracy, and women’s roles in what is deemed as “necessary violence.”

2. Zero for Conduct (France, 1933)

This forty-seven minute film remains one of the two best-known anarchist documents from the first half of the twentieth century—the other being Luis Buñuel’s Las Hurdes: Tierra Sin Pan (Land Without Bread), also a short film of thirty minutes, and also from 1933.

Directed by Jean Vigo, who based the film on biographical experiences in school and his socialist father’s anecdotes concerning contemporary childrens’ prisons, and addressing images of juvenile rebellion against boarding school authority, the film was banned in France until 1945.

After returning from their summer holiday, students are reminded that they must adhere to the school’s strict code of conduct or receive a “zero” for behanvior in their educational records. The faculty and staff are absurd characatures whose outward appearance mimic their inward ineptitude, in the students’ eyes. The children mock the ridculous demands of the adults and ignore their attempts to discipline them.

Because the scenario is depicted from the student’s perspective, we do not realize the serious critique of coercion drawn out by the smallest moments of this film until the final scene. Suddenly, successful in their revolt, we find the rebels hoisting their skull and crossbones flag atop the school while symbolically hurling chamber pots and refuse at the figures of authority on the grounds below.

1. Salt of the Earth (USA, 1954)

Cited frequently by Noam Chomsky as actual engaged filmmaking—in contrast to the disguised right-wing politics of Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront (also from 1954)—Salt of the Earth tops this list because it combines multiple aspects of anarchist form and content with regard to production, distibution, exhibition, and reception.

A neorealist-inspired collaborative endeavor to dramatize the 1951 strike against the Empire Zinc Companty in Grant County, New Mexico, the black and white film deploys actual miners and their families and is constructed around the tensions between the work place strikes and the home front difficulties as gender and hierachical situations are fractured and shifted by intersecting responsibilities.

Although the film is a remarkably collective story—of the miners and their communal struggles to work freely and live the lives they have made—it also uses the microcosm of Esperanza and Ramon’s tale to focus on the gendered aspects of resistance.

Esperanza, who narrates the film, is pregnant with their third child; she at first supports Ramon’s leadership in the workers’ organization but quickly challenges his patriarchal abuse at home. After the striking men are denied the right to continue their collective action, the women of the town take up their places in the picket line, marching for the rights and recognition of all the workers.

Thus, Salt of the Earth is one of the first modern films to directly align feminist and working-class issues without subverting one hierarchy to the other. The film was written by Michael Wilson, directed by Herbert J. Biberman, and produced by Paul Jarrico.

All three men had been blacklisted as communists by the Hollywood establishment. The film was originally blacklisted and banned as subversive but in 1992 was selected by the Library of Congress for archival preservation on the national film registry.

Author Bio: Brian Bergen-Aurand is a professor of film and writes about film, ethics, and embodiment from an anarcho-queer/social collectivist perspective at foreigninfluence.com.