7. Landscape Suicide (1987, James Benning)

In this dual narrative docufiction, Benning turns the two testimonies of Bernadette Protti (a teenager who stabbed her class mate to death) and full fledged serial killer Ed Gein into an account of despondent Americana and social alienation that is brought to a lingering doubtful denouement. When the camera aims its focus diligently on an actress playing the part of Bernadette who is questioned by an unseen interrogator against a flat lifeless wall, we are lead into the world of contingent information.

The interviewer exhaustively questions Bernadette about every detail in long scenes that are made to look like they were violently and abruptly spliced together. The efficiency of the interview comes from the young fragile actress and her monotone vocalizing which so accurately embody an alienated teenage angst and emit a sense of poetic urgency to the scene’s pseudo-reality.

Later, we see a formal replica of the interview when an Ed Gein impersonator expounds a wavering testimony of his murders. The two rigorous interviews are cut with pop scenes of American consumerism and poetic images of snowy backwoods, white churches and a hunter disemboweling his game deer. Benning refuses traditional documentary rhetoric and replaces it with poetic amalgams of violent culture.

8. Colossal Youth (2006, Pedro Costa)

Costa’s slow sedating probe into a squalid Lisbon community on the brink of collapse is accented by his extensive takes and sparse settings. A Cape Verde immigrant plays a Cape Verde immigrant (Ventura), a mythological presence who walks through the poverty-stricken ramshackles of the ghetto, interacting with its Cape Verde refugees. He sits on a bed with his hefty gruff daughter.

The walls are bare-white. Scant light in the room. They both watch a wildlife show, occasionally staring off into space. The tranquil, but sometimes claustrophobic, ambience of Colossal Youth is an immersion into a soporific world of destitute life and an exercise of visual rigor and dead time.

9. Meshes of the Afternoon (1943, Maya Deren & Alexander Hammid)

Though Meshes is more a visual reproduction of the subconscious and its messy mechanisms than a modest exploration of the corporeal world, the temporal/spatial shifts, its fascination with everyday objects, and mirroring of events contribute to its sense of ethereal poetry that refuses to reduce the film to psychoanalytic interpretation.

Instead of unfolding and undisturbed events as with Costa or Barthas, Deren and Hammid construct an image-puzzle where events are constantly mutating and turning against themselves.

The film opens with the first recurrent and fetishistic object, a flower being descended as if from the sky by a synthetic-looking arm. The next image is the shadow of a woman moving against a wall (Deren’s). The film is already endowed with an ethereal and transparent feel through the slow smooth descension of the doll-like arm and the gliding of Deren’s shadow. A dark robed figure with a mirror for a face seems an elusive fascination of the woman’s.

Throughout the film, we are bombarded with close-ups of telephones, knives and keys, not serving exactly as plot devices but everyday objects that are made enigmatic through the woman’s vivid dream.

10. Gummo (1997, Harmony Korine)

A monument of trashy poetry, Gummo is a portrait vignette of unsanitary and weird characters in a small town in Ohio that was struck by a tornado years before. Two teenagers drift through the town on their bicycles. They collect cats to sell to a Chinese restaurant and spend their time sniffing glue. But the film transcends a narrowed narrative. It is rambling, disconnected and discursive; fascinated with psychotic Americana and its gross freak show of strange human behavior.

In an unsimulated scene, two brothers, in an extended scene, smack, hit and jab each other around for kicks. An albino explains her Patrick Swayze crush. And a widowed mother playfully threatens her son by aiming a gun to his head. Intercutting home-movies, grainy records of the townspeople and tornado aftermath bestow a documentary urgency to the episodes.

The shared nihilism of the town’s inhabitants is not far removed from the existential aliens of Bartha’s Koridorius, except Korine’s aliens are trailer trash with a penchant for the perverse that might feel more welcome in a John Waters film.

11. Fata Morgana (1971, Werner Herzog)

Playing up to the idea of equating the poetic with instinct and the immediately emotional, Herzog’s film is a pseudo-documentary whose pieces are constructed not on any preconceived and logical hierarchy but on feelings invoked in Herzog when he surveyed the mirages of the Sahara Desert. Feelings that he, admittedly, could not articulate.

The film was concocted from any material or scenes that Herzog found interesting in one way or another. A narration accompanying the episodes of mirages, sand dunes and African villages is also digressive and sometimes contradictory to the images.

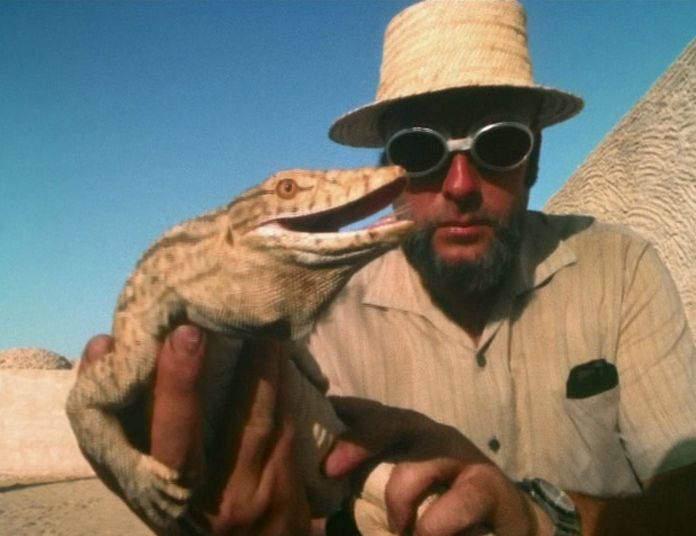

A progression can be seen though in Fata Morgana when Herzog eventually shifts focus from alluring landscapes to more intimate and strange portraits. Particularly, an eccentric musical duo: an old lady with a solemn face and a goggled drummer with stiff body language that segues towards a Roy Andersson-esque absurdity away from the mythic grandiosity of Herzog’s earlier landscapes.

12. Window Water Baby Moving (1959, Stan Brakhage)

Stan Brakhage films the birth of his first child, Myrrena. As his wife sits into a vat of water, we see the shadows of rectangular window frames visually dissecting her swollen belly. Her angelic face is hit by the reflected waves from the pool that surrounds her. She looks patient.

Brakhage visually accents the birth by creating an assaulting barrage of beautiful images and textures. Mixed feelings of repulsion and the sublime arise when we see quick abrupt images. Textures of a woman’s belly revolving across the screen. Her face in agony. A bloodied vulva. And finally a child’s head being reared out of the womb. Stan Brakhage creates a poetic visual kaleidoscope of life and birth.

13. Institute Benjamenta (1995, Stephen & Timothy Quay)

The Quay brothers come from a background of stop motion and puppet manipulation. In their debut feature film, they strove to show people as puppets and the strings attached. Sticking close to their trademark surrealism of Kafkaesque influence, the film is a mystifying experience. Jakob enrolls into the Institute Benjamenta, where they train men to be servants, and ultimately rob them of individuality.

Then on, the film slips into an elusive narrative smothered in hazy shadow and mystery. The institute is a limbo space between reality and dream. A circle of chalk drawn on a board can become an entrance into a deeper and more mysterious fantasy space. And light seems to constantly shift haunting the institute and breathing life into it.