14. L’atalante (1934, Jean Vigo)

L’atalante is Jean Vigo’s swan song, who died at the age of 29 from tuberculosis while shooting the film in harsh weather conditions. The film is replete with one gemlike spellbinding scene after the other. The story is simple. An amorous couple, Jean and Juliette, get married and spend time on a barge manned by a scruffy tattooed captain and infested with cats.

The film transcends a simple plotting strategy and instead utilizes enchanting poetic images. Such digressions include a scene where the boat’s captain enthusiastically and in a puerile mood shows the naive Juliette artifacts of his adventurous life. Like a jar that contains his deceased friend’s severed hand. Vigo and Boris Kauffman, his cinematographer, elevate the film’s simple story of shaky maritime marriage by underscoring it with images of a smoke-enveloped barge and rowdy cramped Paris bistros.

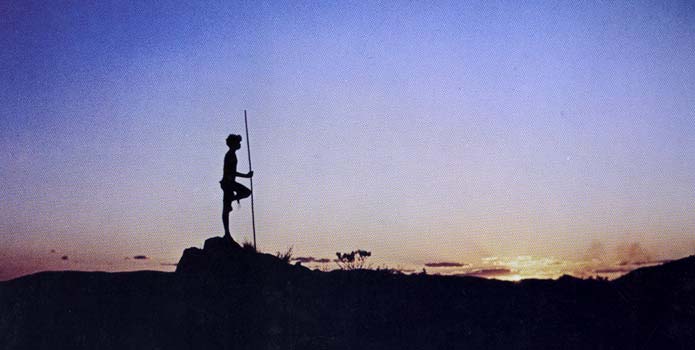

15. Walkabout (1971, Nicholas Roeg)

The Australian outback is the ochre canvas for Roeg’s discursive narrative and lingering camera in Walkabout. A father in a psychotic episode brings his two children to the savage desert, lights the car on fire and shoots himself in the head.

The uniformed girl and her toddler brother then roam through the outback, a threatening land mottled with lizards and scorpions. They meet an aboriginal who helps teach them basics of survival and an erotic tension develops between the girl (Jenny Agutter) and the young native.

In a scene initiating the girl into the wilderness of the outback, she nakedly and sumptuously swims in a natural pool of water. Roeg’s visual exploration of native Australian land heightens the sexual element further and juxtaposes a picture of nature as an idyllic and infinite landscape with the stale monotones of civilization.

16. Damnation (1988, Bela Tarr)

In a purgatory wasteland, big coal dumping cars are slowly dragged back and forth by a high cable. They make fat sounds of grinding metal. The camera slowly and diligently traces back through a window and reveals a silhouette of a man peering out at the pallid bleak scene.

An envious man wallowing in his misery in barren rain-drenched country. He lusts for a married woman and when receiving a job offer to smuggle some goods, he hands the job to the woman’s desperate husband, knowing it would distance him from his wife Karrer. Damnation plays like a sedative injected into the brain, leaving you with visually rich images of slow repetitive movements, black and white squalor, and human degradation.

17. The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat Station (1896, The Lumiere Brothers)

Though the Lumiere brothers sought to simply record the everyday with their newly invented Cinematograph, their short documentations of human behavior should be lauded for catching fleeting moments of industrial bustle and the busy and energetic movement of the people caught up in this age of new invention.

The Arrival of a Train is 50 seconds of quotidian poetry. The Lumieres film a crowd waiting for a train at a station. They wait on the sun-baked platform patiently as other people deboard. The film is a great exercise in movement and rhythm. The film builds up momentum by showing the distant approaching train.

As the train fills one side of the frame, the denizens crowd the other side. Rhythm escalates when the frame is quickly filled with figures moving right and left. This commotion of movement and the visual direction of the train creeping up closer and closer to the frame resulted in people frantically leaving the theatre where it was shown.

18. Beau Travail (1999, Claire Denis)

Claire Denis choreographs relentless military exercises into a poetic spectacle. The film is fluid from start to finish, its imagery highly expressive. Power struggles unfold between sergeant Galoup (Denis Lavant) and one of his recruits, with implications of homo eroticism.

Denis uses sedating silences and a smooth gliding camera to opt for a more immersive and ethereal look at these Legionnaires. Military life is denigrated down to a bunch of meaningless tasks like ironing and drying clothes. In another scene, the soldiers stretch their bodies across a sandy wasteland, their movements graceful like the slowly roving camera that almost worships the figures.

At the end of the exercise, the soldiers slump backwards, resting their bodies on the sand, looking like graceful corpses. They are further mystified by the camera’s slow and curious panning and tilting around their bodies.

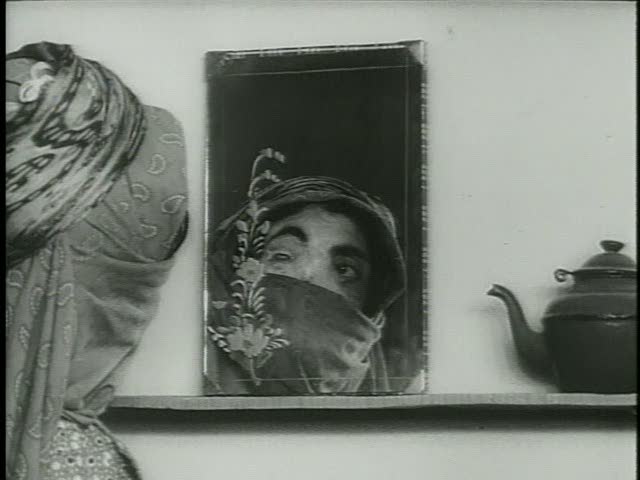

19. The House Is Black (1963, Forugh Farrokhzad)

A devastating and metrical look into a leper colony, The House is Black is a seminal film in Iranian as well as world cinema. Farrokhzad is Iran’s renowned poet; this, her only film, intercuts images of “ugliness” with images of transcendence and faith, Farrokhzad’s ethereal poetry read over the images providing yet another layer of the oneiric.

We see a man trail back and forth the edge of a building. As he gets close to each window, we see a close-up of what’s inside each one. Glimpses of lepers glancing out, their expressions enigmatic, their bodies still. They stare out directly at the camera in an effort to transcend the screen and their their own perceived “ugliness”.

20. Leviathan (2012, Lucien Castaing-Taylor, Verena Paravel)

A paragon of docu-poetry, Leviathan visually explores the goings-on of a fishing boat. It is not a portrait of the fishermen. They are only one part of this grandiose visual exploration. The camera curiously probes the boat and the crewmen’s ordinary working days at catching and gutting their fish. In a scene, the camera roves over the boatmen’s tattoos. No narration is imposed to expound on any of the events or the personalities of the crewmen.

The fishing boat becomes to be seen as a killing machine through its visuals of bloodied decks, dead fish slopping left and right and its imposing and grinding machinery. Near the end, the film is relieved from its visual bombardment by showing one of the crewmen, now tired after a day’s work, dozing off in front of a television. The static camera and long take invoke a feeling of sedation and stillness.

Author Bio: Hassan Husseini is a film fanatic from Lebanon and currently resides in Newcastle upon Tyne, England. He has a BA in Graphic Design and has just finished a BA in Film Studies from Northumbria University. His research includes European Cinema, Sex and Transgression in the films of Pier Paolo Pasolini, Serial Killers in film, and the representation of death in cinema and television.