Wherever a superfluous amount of franchises littered with meaningless characters and repetitive formulas plagues the realms of horror cinema, there will also be an opportunity for great works to spring amidst the chaos. Such films may redefine, revolutionize and transcend the genre, and constantly capture the essence of why horror stories were told in the first place.

While many continue to recognize them for the familiar tropes that decorate its surface, others are able to recognize the hearts and minds that give meaning to the nightmarish images that run rampant on the screen. While they are horror films, they tackle a multitude of ideas, issues and themes, and showcase feelings of anger, despair, mayhem and even the promise of optimism.

The 22 films being honored are not solely meant for cinephiles and horror fanatics, but also for folks who are not necessarily well versed with the genre and may want to engage in a freakishly exciting (and hopefully insightful) experience.

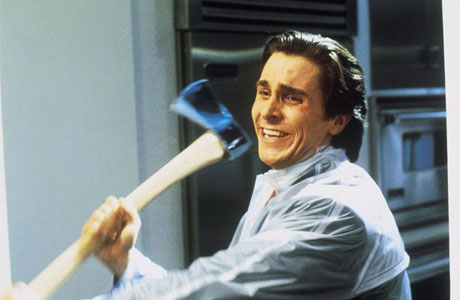

1. American Psycho (2000)

“I like to dissect girls. Did you know I’m utterly insane?”

That is one of the many bizarrely disturbing things the film’s narrator, Patrick Bateman, shares so casually with other beings. Bateman, played almost to perfection by an obsessive Christian Bale, is a successful banker who spends his days applying expensive skincare products to reaffirm his youth, clubbing and indulging in lavish meals with his colleagues, working out, having sexual intercourse with various women (and sometimes working out during any given intercourse), immersing himself in the music of his favourite bands, renting movies and of course, murdering people.

The film, directed by Mary Harron, is a subjective experience, and is deliberately vague on how much of what is seen through Bateman’s eyes has actually transpired or whether it is all in the confines of his enigmatic mind. Harron’s command of the ambiguous, labyrinthine nature of the narrative is where American Psycho’s brilliance truly lies.

Bateman is not unlike the psychotic Alex Delarge, the unreliable narrator in Stanley Kubrick’s hellish dystopic vision of A Clockwork Orange (1971), as he presents himself as a man with much chaos and madness to unleash upon society. And while both men would be waging their own against the world, it would seem that neither of them are the true villains of the piece.

Like a reckless child, Bateman does his very best to gain an excessive amount of attention by getting away with murder and feed his “super god” ego. Yet with all his zany efforts, there appears to be a unified willingness on the part of the shallow, elitist business types to ignore the nasty nature that lurks beneath the skin of their kind.

The film is horrifying in many respects; whether it be through Bateman’s abrupt need to exterminate those he considers beneath him or those who seemingly mock him, or even through the implication that the company he keeps are a cold hearted, desensitized and robotic bunch, who are involved in their own secret conspiracies.

On the bright side, Bateman can always escape an uncomfortable situation by uttering some of his favourite magical words: “I have to return some videotapes”. As this film, a period piece, does supposedly criticize Reagan Era politics, it would be beautifully ironic if Bateman had actually rented John Carpenter’s 1988 satire, They Live (where the corporate and elitist forces of the world are in fact, evil alien beings, secretly controlling the rest of society) and failed to see the resemblance.

2. Shadow of the Vampire (2000)

One does not have to be an expert cineaste to recognize the iconography of Nosferatu (1922), the classic silent film adaptation of Bram Stoker’s 1897 vampire novel, Dracula.

From the dark shadows and silhouettes that helped define German Expressionist Cinema, to the lean, menacing figure of Max Schreck’s Count Orlok , F.W. Murnau’s masterpiece has influenced a great number of auteurs and films (including Guillermo Del Toro and Tim Burton) and even spawned a few legends that claim that its show-stealing star, Max Schreck, was in reality, a vampire.

Shadow of the Vampire does not pretend to justify such claims as it dives into the making of the magnum opus; instead it takes on the ambitious task of fully exploring the “What if” scenario (immediately encouraging purists to forgive the many anachronisms) and framing it within a Faustian context, where Murnau (played by a mad eyed John Malkovich) promises the monstrous Schreck (played almost unrecognizably by possible real life vampire, Willem Dafoe) some human sacrifices if he does his very best to add a much needed reality to his onscreen persona. Schreck, being the bloodthirsty token of his kind, wholeheartedly agrees to said endeavor.

The film humorously plays with “slasher film” conventions as Schreck wreaks havoc on the various locations needed for the shoot, but Schreck is really just a rabid dog unleashed upon the innocents; Murnau is the deadlier, scarier monster, one who is willing to push his art to the point of madness without caring one bit about the consequences of his bargain.

The film boasts deliciously over-the-top expressionistic performances (in keeping with the unique feel of the period setting) and playfully moves between darkly absurd comedy and liberating gothic horror, and in the process, manages to be a far more frightening experience than the movie it mythologizes.

3. The Devil’s Backbone (2001)

As a young child, Guillermo Del Toro claimed he saw monsters in his bedroom at night, which would often lead him to urinate in his bed out of fear.

Time passed, and he eventually confronted the beings one night, and made a pact of friendship if they allow him to go to the bathroom. He never saw them again, but he never shook off his fascination with the otherworldly and the supernatural, using cinema to honour the memories of the apparitions he saw and the stories he read, while simultaneously crafting and establishing his own mythology.

In The Devil’s Backbone, Del Toro tells the tale of greed and murder taking place in an orphanage (which is in a more isolated area in Spain) in the final year of the Spanish Civil War. A young boy named Carlos, who is unaware his father’s demise, is abandoned at the orphanage by his tutor, and he soon learns from the resident children that the place is haunted by the spirit of a child, Santi, who disappeared the day a bomb landed nearby.

The caretakers of the facility, Dr Casares and headmistress Carmen, are both in love with one another, but Casares cannot make any progress with Carmen as he is embarrassed about his impotency. Jacinto, an employee who has an intense hatred for the orphanage he grew up in, fulfills a disgusted Carmen’s sexual needs in order to gain access to her keys to find the hidden gold (meant for the Republican troops) he learned about, stashed somewhere on the grounds.

It would appear that for the longest time, this home has been a symbol of cynicism; a limbo where dreams and hopes are trapped in a web of despair. The phantom himself represents these notions, and Del Toro gives him a terrifying visage to the uninitiated, but a painful and tormented soul to the more sympathetic.

Taking his own personal ghostly encounters into account, Del Toro successfully weaves together childhood fears, complex adult dilemmas, and long-standing grudges into the narrative, leaving the period setting to be an interesting but nonintrusive backdrop. Accompanied by a beautiful music score, and dedicated performances from the actors, the film becomes a unique addition to the cinematic ghost story.

4. Shaun of the Dead (2004)

A common misconception with horror films and stories is that they have to be made up of obvious images of monsters from biblical writings, psychedelic fantasies and pop culture extravaganzas, when the simple facts of daily human existence can be scary on their own…like being an adult. As a case in point, take a look at the life of a salesman named Shaun.

In addition to this dead-end job at an electronics store, Shaun (played brilliantly by Simon Pegg) has problems with Liz (his girlfriend), his mother, his stepfather and the general direction he has taken with his life thus far. He is more content to goof around with his slacker of a friend, Ed (played by the hilarious Nick Frost), going to the pub, playing video games and listening to his favourite albums from the 1980s.

His situation can be best summed up in an exchange he has with a young co-worker, who is disrespectful and unmotivated. Shaun tells him: “I know you don’t wanna be here forever. I got things I want to do with my life.” The boy replies: “When?”

The fact that a zombie outbreak takes place in that time frame is sheer coincidence, but also a useful dramatic convenience. The infected beings (Shaun forbids them from using the “Zed Word” that they encounter allow them to see the parody that is the apparent “zombification” of society, where life is a routine state of meaningless.

Shaun (with the occasional assistance of dimwitted Ed) becomes more productive than ever and fights his way through the apocalypse to save his loved ones, and hopefully, win Liz back in the process (there is nothing better than a horde of zombies to solve and spice up ones romance is there?).

On a side note, he may also be doing this to keep his “bromance” with Ed alive, as they seemingly cannot afford to miss out on playing Timesplitters 2 (a cult video game, which features a cast of undead characters to boot).

The film may be funny and scary throughout, but it has a heart and a mind that shine throughout. Edgar Wright, director and co-writer (with Pegg) of the film, is a dedicated fan of the “Living Dead” collection created by politically minded auteur, George Romero.

Pegg and Wright combine the humour brought on by rapid-fire dialogue and witty visual gags, with an ample supply of social satire and subtext to support the ambitious narrative. Shaun of the dead may have been made by film geeks, but it is bound to entertain and impress casual moviegoers and nerds alike for its intelligence in crafting an emotional and joyous thrill ride.

5. Bug (2006)

Agnes is a waitress, who lives alone in a cheap motel. Her past is tormented by abuse and loss, and she indulges in alcohol and drugs. A friend introduces her to Peter, a mysterious man who claims he is soldier and subjected to experiments by the army. With the disappearance of her son some time ago and the threat of her ex-husband returning, Agnes becomes closer to Peter, and she is soon enveloped by his infectious paranoid fantasies of bugs and military surveillance.

Based on a play by its screenwriter Tracy Letts, Bug goes out of its way to make the viewer feel just as uncomfortable as its characters. William Friedkin, director of The Exorcist (1973), elevates the claustrophobia and tension to an abnormal degree, creating an atmosphere that reeks of insanity.

Anger, frustration, madness, sexual repression and violence are all personified through the characters’ interactions with one another, and the actors give performances that are so convincing one might think they were on the verge of tearing the skin clean off their bodies.

This is an ingenious psychological thriller in the sense that there is no outside tormentor(s) to be seen or heard, and remains a subjective experience throughout. The film is an unnerving journey where the viewers may be left scratching their head (and probably their bodies too) once it is over, and that means it has certainly struck a nerve.

6. Fear(s) of the Dark (2007)

A horrible old man who lets his monstrous dogs attack people; A socially inept university student whose childhood obsession with insects and first romantic relationship intertwine; An young girl who cannot escape the clutches of spirits and tormentors; A monstrous beast that claims innocent victims; a man seeking refuge in a house that holds a twisted secret; These are the stuff that nightmares are made of.

Horror has always been welcome in animation, especially where the freedom exists to create surreal slices of unconscious fears and desires. A different director handles each of the five segments, and the styles range from two dimensional anime animation to three-dimensional animation. Each story is also inked in glorious black & white, and not for the sake of any gimmick either.

Nay, the colour scheme is utilized to the fullest of its experimental capabilities, becoming a character in each of the stories, and allowing the style to ooze into its substance and vice versa. Given the variety that these segments boast, there is going to be at least one “fear” that will get under the viewer’s skin.

7. [Rec] (2007)

While filming a documentary about a nightshift team of firemen in Barcelona, a reporter and her cameraman soon join the crew as they investigate a distress call about a woman trapped in her apartment. With a couple of police officers already waiting at the scene, the group encounters the victim, who becomes aggressive and violent.

As the narrative progresses, the firemen, the documentarians and the residents of the building are literally locked in a state of confusion, disbelief and extreme fear, as the military and police seal the building, preventing anyone from exiting. Gradually, the characters are pushed closer and closer to the terror waiting upstairs.

While The Blair Witch Project (1999) made the “Found footage” genre a popular phenomenon, it is movies like [Rec] that come very close to perfecting it. With a tight running time, the film manages to maintain a terrifying atmosphere and an uncomfortable sense of claustrophobia even as characters move from one room to another.

The movie succeeds in building a cynical barrier around the excitement of seeing these characters trying to escape their ordeal; in saying that there is no one they can depend on or trust. Their lives are in the hands of the forces outside the building and whatever evil is hell-bent on claiming them next, and that is a terrifying notion.