18. Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1974) – Terry Jones, Terry Gilliam

Country: United Kingdom

In an era where Ealing Studios had long since ended its run for British comedy, a wacky troupe formed in 1969 began making films based on their sketch comedy and ultimately changed the world of comedy forever. The Monty Python troupe (consisting of John Cleese, Eric Idle, Michael Palin, Terry Jones, Terry Gilliam, and Graham Chapman) fused the historical, the psychoanalytical, and the downright silly together to make a series of comedies that became endlessly quotable and memorable.

Their first foray into feature-length filmmaking And Now for Something Completely Different (1971) brought an unfamiliar style to worldwide audiences and received mixed reviews, but their sophomore effort, a macabre and zany re-telling of the Arthurian legend of the quest for the Holy Grail, set the troupe up as unsung heroes of a modern style of comedy.

The story follows King Arthur, desperately seeking knights to accompany him on a quest to Camelot. Within the first 25 minutes of the film, this quest is immediately dismissed, for Camelot is deemed “a silly place.” Immediately, God calls upon Arthur and his knights to seek the Holy Grail. Now with a full-fledged quest from the Lord, the group disbands to locate the blessed cup, getting into as many ridiculous shenanigans as possible leading up to an ambiguous ending.

Despite certain claims that Monty Python’s two narrative features of the era (Holy Grail and Life of Brian [1979]) deviated from the more-favorable sketch pieces Monty Python was known for with its TV series Flying Circus, this film proved to be a cult classic that still remains one of the finest comedies ever made. In an era where the slapstick comedies of yore were no longer as popular, Monty Python managed to indeed make something completely different out of something already familiar.

19. Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975) – Pier Paolo Pasolini

Country: Italy

After the successes of Italian Neorealism in the 40s and 50s, as well as successful artistic run in the 1960s, Italian cinema continued to push the boundaries of style and narrative. Fascism seemed to be a main point of discussion in the eyes of some directors (like Fellini’s Amarcord), but when taken out of its autobiographical context, Pasolini managed to make one of the most unsettling and soul-crushing films ever made.

Taking place after Mussolini’s fall in 1943, four fascist libertines get together and formulate a hedonistic society in a secluded mansion where eighteen boys and girls have been kidnapped and subjected to the fascists’ sexual and physical desires. In unspeakably horrifying tasks, the helpless children are forced to engage in sexual debauchery, psychological intimidation, and the consumption of human waste all while adhering to strict atheistic rules under pain of death.

Despite the film’s horrible graphic nature and nauseating plot devices, Salò is indeed an excellent satire. It is hard to watch, but the anger and disgust the film brings about is a cathartic reaction that was ultimately Pasolini’s intent. It is one of those films that needed to be made in order to give a voice to atrocities that most likely went unsaid in fascist era Italy.

Not for the weak of heart, but highly influential towards the likes of world-renowned filmmakers such as Michael Haneke and Catherine Breillat, Salò is an important piece of cinema that pushed the boundaries of what could and could not be shown.

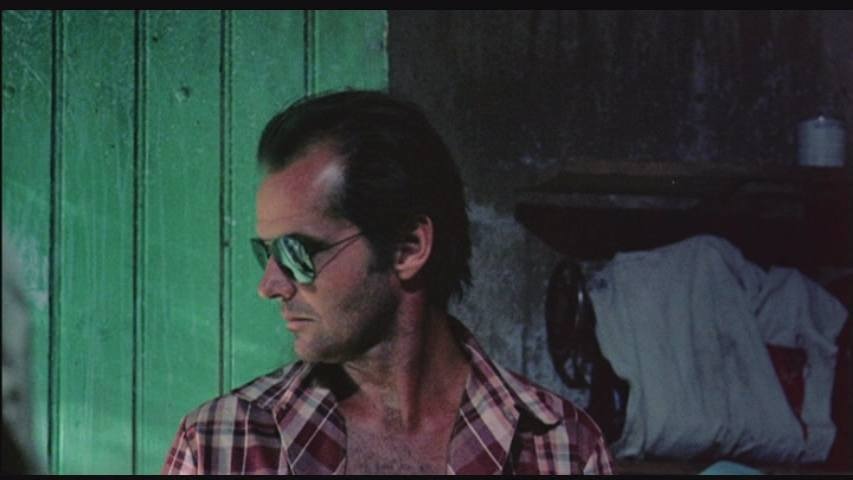

20. The Passenger (1975) – Michelangelo Antonioni

Country: Italy

While Italian filmmakers like Fellini and Pasolini made films about the effects of fascism in their 70s output, Antonioni decided to tackle colonialism in one of the finest films of his extensive career. Co-written by Mark Peploe and auteur-theory scholar Peter Wollen, and expertly shot by Luciano Tovoli in sparsely different locations such as Chad, London, and Barcelona, The Passenger has an international feel that says a lot in its two-hour runtime.

Telling the story of an American journalist (played by Jack Nicholson) who takes on the persona of a dead British businessman in Africa, the story unleashes a torrent of mystery and murder as the supposed businessman turns out to be an arms dealer mingled with the local civil war happening in postcolonial Chad. Traveling from Africa to the U.K., the reporter continues his ruse, eventually teaming up with a nameless French girl (Maria Schneider) who becomes his lover.

A definite technical masterwork of cinema (the film’s seven minute long final shot has gained a lot of praise and recognition) and storytelling, The Passenger explores the human condition in ways that only Antonioni could direct: slow and brooding, yet poetic and beautiful.

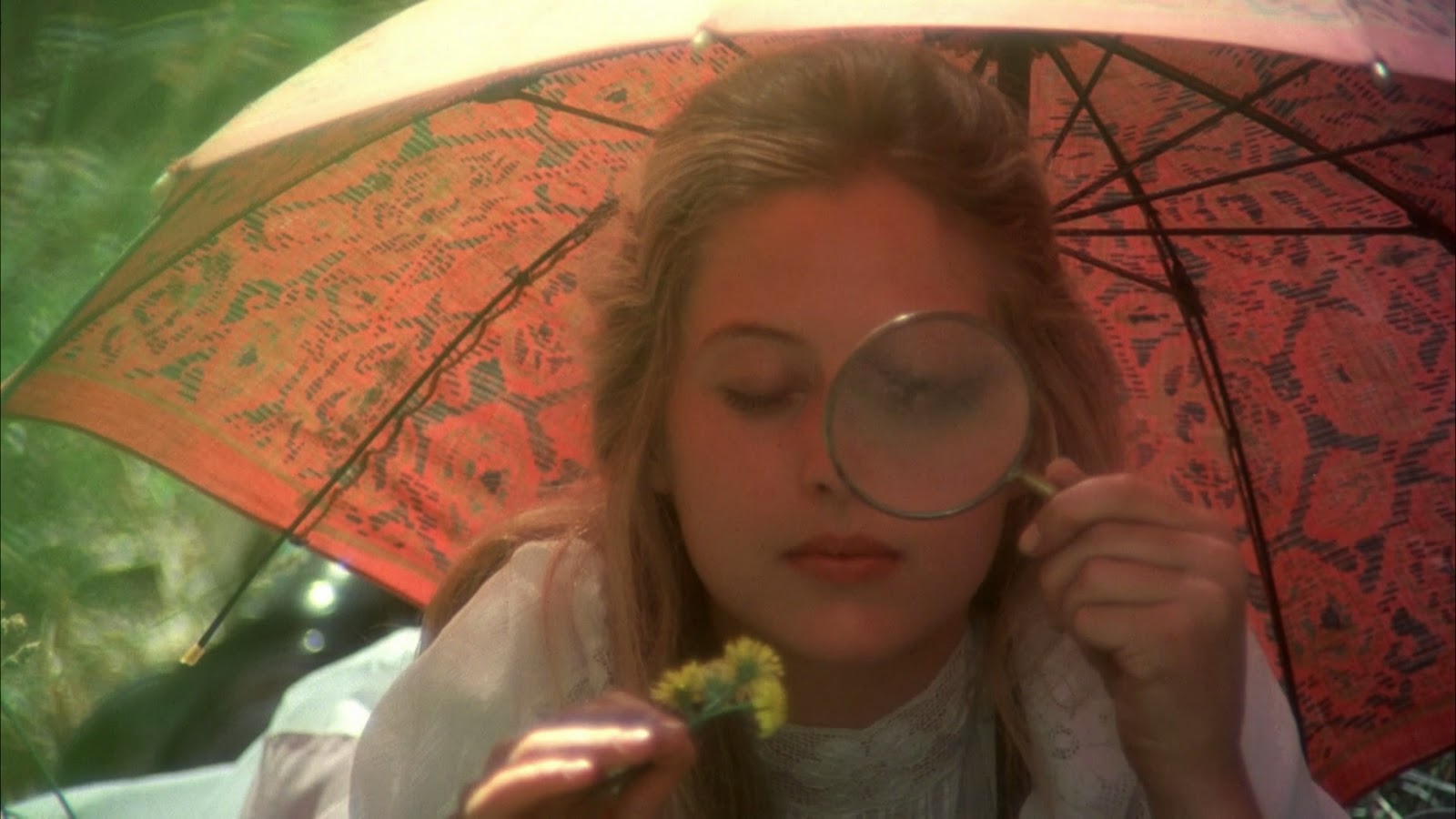

21. Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) – Peter Weir

Country: Australia

While Walkabout may have spurred the Australian New Wave, Picnic at Hanging Rock was an example of purely Australian filmmaking. Made by an Australian and based on an Australian work of fiction, Picnic at Hanging Rock broke through the limits of one’s country and took the world by storm. Its ambiguity, defiance of single interpretation, and creepy near-horror vibe make this film a lasting example of storytelling done right.

Set in 1900 in Australia, a group of schoolgirls are taken to a large landmass in the wilderness known as Hanging Rock, a bizarre formation shrouded in mystery. The peaceful picnic is disturbed when three of the schoolgirls and one of the teachers inexplicably go missing after a bizarre phenomenon puts the group to sleep. After authorities are alerted, more cryptic clues as to the disappearance of the girls are made known and even supernatural visions and occurrences lead some townsfolk to deeper investigations into the disappearances. Ultimately, the film leaves the viewer with more questions than answers.

Full of beautiful shots, Picnic at Hanging Rock can veritably be mistaken for a typical period piece, but deep down, the film’s sexual imagery and creepy plot twists make this film transcend one particular genre. Some view it as a coming-of-age tale while others call it an overt horror film. Needless to say, Picnic at Hanging Rock is a masterpiece of its era.

22. Ceddo (1977) – Ousmane Sembene

Country: Senegal

One of Africa’s most prolific filmmakers, Ousmane Sembene focused most of his work on philosophical and post-colonial character studies in Africa. His treatment of women in film also stands out. After reaching prominent success as an author, Sembene began making films. After modest success with his 1973 film Xala, Sembene became even more renowned with Ceddo.

Taking place in a tribal village in an unspecified time period, Ceddo tells the story of a group of “outsiders” who kidnap the daughter the King Demba War to denounce a forcible conversion to Islam. After a challenge is set, the notions of religion and culture become further conflicted as blood begins to be shed. Where one side picks tradition, the other opts for religion and the disagreements escalate into further violence until the film’s bleak ending.

A proclaimed Communist and subvert of Islamic traditions, Sembene criticized many things in his film than simple religious debates. His film is rife with imagery of tribal unity and principles which excellently debate the mores of religious introduction into the tribe (Christianity also plays a large part in this film).

Sembene’s ambiguous time frame also sets the film up as a marker for something that never truly ended, where culture is threatened by unstoppable forces that lead to further conflict. Culturally significant, depressingly violent, and well-told, Ceddo is a landmark in Senegalese and African cinema.

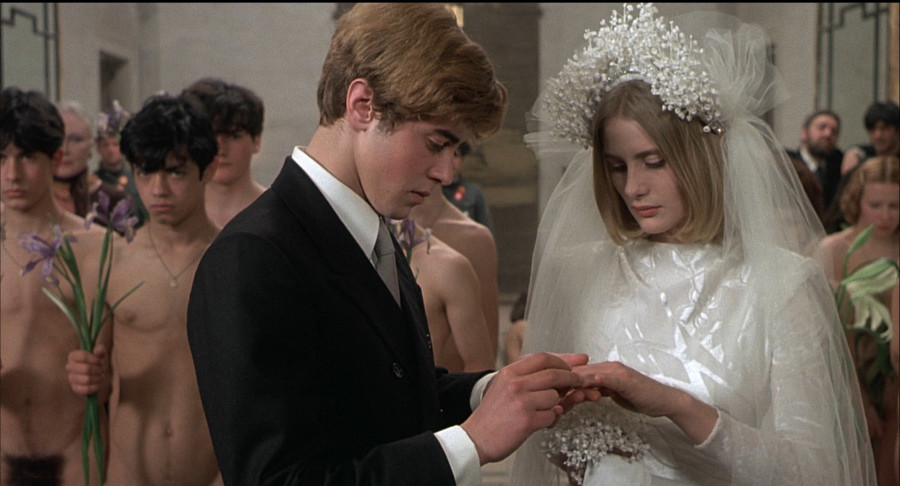

23. The Tin Drum (1979) – Volker Schlöndorff

Country: West Germany

Black comedy in the late 1960s and early 1970s seemed to be the way to go in order to get one’s point across, especially in Europe. Volker Schlöndorff’s take on Günter Grass’s novel of the same name was both poetic and very controversial yet has stood the test of time as an important work of cinema and storytelling.

After a brief chronicle of the conception of his parents, the narrator Oskar tells of when, at the age of three, he is given a tin drum by his parents. After witnessing the complicated nature of adult life, he throws himself down a flight of stairs with the intention of never growing again. His ploy is successful and he remains a three-year-old for the rest of the story while maturing psychologically.

The film’s controversy lays in its depiction of a child undergoing general adult thematic elements, most notably sexuality and war as the youthful Oskar (played by the expressive David Bennent) witnesses bloodshed, infidelity, and hardship with sheer innocence. Where even at 20 years old, Oskar still sees through a three-year-old’s eyes.

This lengthy film almost plays as an inverse Little Big Man as Oskar sees his people (a sect of Polish people eventually ghettoized by the Nazis) placed under scrutiny, his father becomes a proud Nazi officer, and begins seducing his father’s mistress, all culminating into a decision on whether to grow up or stay young. The film is rife with metaphoric imagery, whether it be the titular tin drum or Oskar’s glass-shattering scream, The Tin Drum is an arthouse work of epic proportions.

24. Mad Max (1979) – George Miller

Country: Australia

After a series of rogue cop films over the decade in New Hollywood like The French Connection (1971), Dirty Harry (1971); and an entire Italian police genre (Poliziotteschi), the genre was saved from becoming stale with George Miller’s Australian cult classic Mad Max. Fusing a post-apocalyptic narrative with rural policing, Mad Max delivered a story full of wacky characters and set Mel Gibson up as a rising star for the next few decades.

Taking place in future Australia, Mad Max centers around Max Rockatansky (Gibson) and his fight with a ruthless biker gang after killing their leader in a car chase at the beginning of the film. After raising the gang’s ire by arresting one of their protégés, Max finds himself retired to keep his sanity, but is ultimately followed by the biker gang who terrorize his family. Forcing his hand to a point where he has nothing left to lose, Max turns the tables and wages a one-man war on the gang.

Despite its daring and promising title, Max does not become “mad” until the last 15-or-so minutes of the film. However, the film’s charm lies in its colorful and larger-than-life characters who dominate the screen with their cars and motorbikes. Led by the sadistic Toecutter, the gang are literal pirates of the road, invoking terror and chaos all around them. Mel Gibson’s near-silent run through the film is both expressive and identifiable as he wears the hardships he endures on his face, making him a quintessential action star.

A big hit in Australia, Mad Max was a sleeper hit of the Australian New Wave, grossing $100 million worldwide and spawning two sequels and an eventual reboot 36 years later.

25. Vengeance Is Mine (1979) – Shohei Imamura

Country: Japan

While the Japanese crime drama found a steady home in the 1970s with Kinji Fukusaku’s Battles Without Honor and Humanity (1973), Graveyard of Honor (1975), and Yakuza Graveyard (1976), Shohei Imamura’s disturbing chronicle of a rebellious man turned murderer tells a far more complex and horrifying story. Vengeance Is Mine is a prime example of Japanese id-focused cinema that has followed Japanese filmmaking since the Japanese youth films of the 1950s and into the gory action epics of today.

Taking place over the entire country of Japan in the early 60s, Vengeance Is Mine tells the biographical story of Iwao Enokizu (Ken Ogata), a Catholic-raised man who initially murders two co-workers in a small town who then embarks on a 78-day killing and extortion spree all over Japan until he is caught by the authorities.

Told in flashbacks while Enokizu is in police custody, the film chronicles Enokizu’s troubled and rebellious childhood, his descent into petty crime, and his eventual lust and bloodlust combined, turning him into a remorseless emotional monster. Made all the more shocking upon the knowledge that Enokizu is based on a real serial killer, Vengeance Is Mine is a lengthy trip into the mind of a serial killer.

Mixed with a bizarre brand of dark humor and shocking brutal violence, the film is hard to watch at times, but its stylish delivery and minimalist cinematography make it an unspoken classic of Japanese cinema.

Author Bio: Josh Schasny is a film studies graduate and screenwriter based out of Montreal, Quebec. A born film buff he loves to get together with people to talk film. He also writes lists, articles, scripts, helps people shoot films, and one day will eventually die.