20. Moon (2009)

Overrun with arresting ideas and details, Moon, Duncan Jones’ directorial debut, orbits perceptions on artificial intelligence, ethics in exploration, loneliness, identity, and more, as we follow astronaut Sam Bell (Sam Rockwell), employee of Lunar Industries. Sam’s nearing the end of a multi-year contract on moon station Sarang, where he’s been the lone human occupant, with only GERTY (voiced by Kevin Spacey), the station’s AI unit, for company.

Due to unspecified interference, the communications mainframe has been damaged, unable to transmit for some three years, furthering Sam’s disconnect from Earth, his family, and his life there. After a routine exercise goes disastrously wrong for Sam, a string of hallucinations has him paranoid, questioning his sanity, and reality. Jones displays visual genius and considerable craft, creating an ethereal, and occasionally frightening meditation on humanity.

19. Insignificance (1985)

Adapted from Terry Johnson’s play, Nicolas Roeg’s film occurs on a summer night in 1954, set in anonymous hotel rooms where the lives of four iconic figures; Marilyn Monroe, Albert Einstein, Joe DiMaggio and Joe McCarthy (though in the film they are simply and slyly referred to as the Actress, the Professor, the Ballplayer, and the Senator), intersect. These recognizable popular culture figures, in typical Roeg fashion, riff on grandiose ideas and floundering emotions.

What begins as trivial digressions gains momentum and significance, buoyed by stellar performances (like Tony Curtis as McCarthy, witch-hunting endlessly in his mind, or Theresa Russell’s Monroe, who, despite her ditzy dilettante routine can still teach Einstein a thing or two about relativity). Insignificance may not be the exacting pedigree of Roeg masterpieces Walkabout or Don’t Look Now, but it’s still a vast, ingenious allegory on fame, life, love, obsession, jealousy, and substantially so much more.

18. Lifeboat (1944)

Hitchcock, known for his innovative and elaborate mysteries, with Lifeboat, fixed his action to a single, oppressive location: a lifeboat. From a story by John Steinbeck and a screenplay by Jo Swerling, Lifeboat follows a group of survivors adrift from the wreckage of a ship sunk by a German U-boat. In turn the survivors — an outstanding cast led by Tallulah Bankhead, which also includes Hume Cronyn, and Heather Angel — find problematic refuge on the ketch.

Eventually they pick up a German survivor from the very boat that sank them, and a psychological war is waged with anxiety and confusion reaching a critical culmination. Utilizing mostly close and semi-close-ups, Hitch makes another exemplar of tragicomic thrills in this overlooked jewel from his heyday.

17. Carnage (2011)

No stranger to the chamber film, Roman Polanski — whose earlier films like Knife in the Water, Repulsion, could also be categorized as such — here takes Yasmina Reza’s Tony winning play, The God of Carnage, and creates a pitch-black comedy, stacked with A-list actors. After their children get in a schoolyard brawl, two groups of parents decide to meet in a Brooklyn apartment to discuss the matter.

At first the parents, the Cowan’s (Kate Winslet and Christoph Waltz) and the Longstreet’s (Jodie Foster and John C. Reilly) hit it off smashingly, with a tidy resolution looming on the horizon, but of course, that’s not going to happen. As matters escalate and personal attacks proliferate, Carnage becomes a high-powered misanthropic comedy, and at a deft 80-minutes, its pace is dizzying.

16. Gravity (2013)

Alfonso Cuarón ably and realistically depicts the dangers of spaceflight in a technically dazzling 3D film about scientist Dr. Ryan Stone (Sandra Bullock) and veteran astronaut Matt Kowalski (George Clooney) as they work on a NASA shuttle orbiting earth.

Gravity’s at its best when focusing on the human drama of isolation, using elegant weaving camerawork during masterly long takes (the 13-minute opening shot is stunning), though arguably the film falters heavily via emotional blackmail to evoke audience response.

But the high-tech prowess on display is staggering, and it’s easy to forgive the dramatic shortcomings in the face of such towering visual tableau and mind-blowing special effects. For a mainstream movie, Cuarón gracefully disengages the blockbuster and puts it untouchably into orbit.

15. Reservoir Dogs (1992)

Quentin Tarantino’s directorial debut, the neo-noir crime caper, Reservoir Dogs, was made on the cheap, with a dedicated cast, and utilized a single primary location, to make one powerful honey of an homage to the heist-gone-wrong subgenre.

The plot concerns a group of LA-based criminals, mostly unknown to each other, roped into a heist by “Nice Guy” Eddie Cabot (Chris Penn), whose old man, Joe Cabot (Lawrence Tierney), is a major mob boss. Hidden amongst their number is “Mr. Orange” (Tim Roth), actually Detective Freddie Newandyke, infiltrating the gang, and setting the stage for things to go south in bloody, thunderous fashion.

14. Dog Day Afternoon (1975)

Sydney Lumet’s heartening crime drama, Dog Day Afternoon, is essential 1970s cinema, perfectly expressing the zeitgeist, and winningly reinforced by actors Al Pacino, Chris Sarandon, John Cazale, and Charles Durning. Based off a real incident, this richly detailed story is riddled with absurdist humor as it follows an afternoon with Sonny Wortzik (Pacino), an inept, anxiety-ridden bank robber.

Sonny, a gay man, wants the money from the robbery to pay for his lover’s sex-change operation. With a relevant obiter dictum on America’s tendency for meida overkill and victim-blaming (Sonny’s chants of “Attica! Attica!” really bring that idea home), offer what’s ultimately a bittersweet, journalistic reverie.

13. The Breakfast Club (1985)

A linchpin of 1980s American pop cinema, especially of the coming-of-age variety, The Breakfast Club is the quintessential John Hughes picture. Featuring all the major players in “The Brat Pack” (Emilio Estevez, Anthony Michael Hall, Judd Nelson, Molly Ringwald, and Ally Sheedy), in the roles they’re each best known for, the film occurs during an all-day Saturday detention at Shermer High School in suburban Illinois.

Each of students in detention are emblematic of a different clique; an “athlete”, a “basketcase”, a “brain”, a “criminal”, and a “princess”. With resonant, relatable themes, a killer soundtrack, great dialogue, and nostalgia, too, The Breakfast Club is, rightly, a beloved, contemporary classic.

12. Ex Machina (2015)

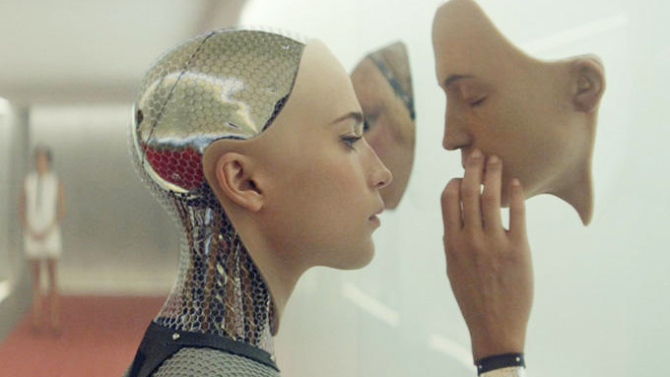

Alex Garland first made his name as a novelist (The Beach), then as a screenwriter (his works include 28 Days Later, Sunshine, and Never Let Me Go), cut his director teeth with Ex Machina (which he also wrote). A voyeuristic film, Garland’s philosophical tale starts with Caleb Smith (Domhnall Gleeson), a programmer for a search engine called Bluebook, who’s invited to meet and stay with it’s illusive CEO, Nathan Bateman (Oscar Isaac) on a new project.

This project involves artificial intelligence in the form of Ava (Alicia Vikander), and instantly an objectifying gaze falls upon her — this objectifying is fitting, considering she’s a robot — and soon tenets of male/female Weltanschauung abounds.

It’s more subversive and thoughtful than its surface suggests, and, interestingly, Charles Perrault’s classic fairy tale Bluebeard is reworked and given eerie homage (consider bearded Nathan’s “robot wives” and Ava’s self-aware relation to them, for instance). Despite the hemmed in limitations that can come with a chamber-piece, Ex Machina eclipses such notions, and grasps for big ideas while articulating a dystopia that’s magnanimous to AI but not so much towards humanity.

11. Glengarry Glen Ross (1992)

This shattering adaptation of the David Mamet play is David Foley’s foul-mouthed masterpiece. Laced with profanity — hearing Jack Lemmon spit out expletives like “cock-sucker” and “motherfucker” with such bravado is somewhat of a sensation, admittedly — and misplaced testosterone, Glengarry Glen Ross is about a group of desperate, competitive real-estate salesmen, fighting for their jobs after a frightening announcement at work, courtesy of Alec Baldwin’s demonic motivator Blake (“What’s my name? FUCK YOU, that’s my name,” he howls at them).

Not without sympathetic characters, such as Lemon’s Shelley “the Machine” Levene (truly a modern icon to loserdom), Foley presents a ruthless treatise on capitalist values, capturing the way men relate, bond, intimidate, compete, and tear each other down.