10. The Exterminating Angel (1962)

Avant-garde surrealist Luis Buñuel made one of his most memorable films with The Exterminating Angel. This delicious masterpiece ridicules mob mentality as it unravels, telling the sordid story of an elegant dinner party that spins into strangeness and disarray as the guests develop a mass mental illness whereby they can’t bring themselves to leave the room. T

he required codes of polite society are made ragged in Buñuel’s darkly hilarious gaze. There are several unforgettable dream sequences, too, a sort of trademark of Buñuel’s, making the comedy at hand even more macabre, and the satire and eccentricity is undeniably disturbing as well as being subtly profound.

9. My Dinner With André (1981)

Louis Malle’s My Dinner with André simply consists of two old pals, New York intellectuals — uptight actor-playwright Wallace Shawn and outré avant-garde theater ace André Gregory, playing fictionalized versions of themselves — talking over dinner. It sounds unbearable and mincing, doesn’t it?

Well, thanks to Malle’s assured direction, believable performances, and artful, incredible discourse, this dinner nourishes both body and mind.André and Wally’s discussions on authenticity, enlightenment, love, art, theater, travel, and holy moments, amongst other far-ranging topics, are frequently funny, believably natural, and as compelling and spine-tingling as any big budget special effects-fuelled extravaganza. My Dinner with André is a satiating experience, highly flavored and deliciously audacious.

8. 12 Angry Men (1957)

Sydney Lumet’s first film is a mélange of monochrome — thanks in part to Boris Kaufman’s excellent lensing — all perspiry close-ups and claustrophobia, as a twelve man jury deliberates the outcome of a murder trial. With tense treatment, stellar performances (Henry Fonda, and Ed Begley especially), an unblurred narrative full of high stakes, and moral authority, making for one compelling thriller.

While the story appears rather run-of-the-mill, Reginald Rose’s script has many cloying clichés, it still works due to Lumet’s tightly drawn atmosphere and real-time energy. It’s a modern and realistic movie, and, while Lumet would go on to make many more, 12 Angry Men may be his most athletic and remarkable film.

7. Clouds of Sils Maria (2014)

One of Olivier Assayas’ most intelligent and mystifying masterpieces (alongside Irma Vep and Summer Hours), Clouds of Sils Maria makes for a meta psychodrama that’s haunting and serene. Maria Enders (Juliette Binoche) is an aging A-list actress and Valentine (Kristen Stewart) is her ravishing young assistant, and they spend the better part of the film in seclusion in the remote Swiss canyons as Maria prepares for what could be her comeback performance.

There’s more to the preparation then she anticipates, and they walk a precipice that’s often unclear and ever shifting, like the titular Majola Snake cloud formations in their midst.Binoche and Stewart are first-rate, each proving to be amongst the finest actors of their respective generations, making for an intelligent, and evocative film.

6. Das Boot (1981)

A claustrophobic nightmare, remarkably rendered, Wolfgang Petersen’s pulse-pounding chronicle of life and death aboard a German WWII submarine, is an unforgettable anti-war film. With equal parts intelligence and anxiety, the slow build-up of tension in commander Jürgen Prochnow’s fateful mission is a nerve-shredding ordeal.

Petersen, who’s perhaps best known for his American films The Perfect Storm and Air Force One, is at the height of his considerable directing powers with Das Boot, which outdoes it’s smart source material — Lothar-Günther Buchheim’s 1973 best-selling novel of the same name — and is considered one of the finest films in all of German cinema.

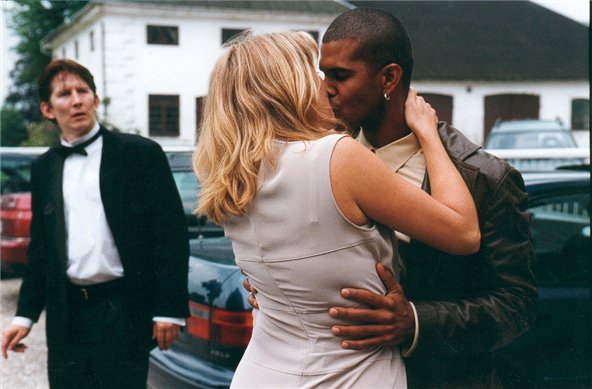

5. The Celebration (1998)

Using the gimmicky confines of the Dogme 95 manifesto to his maximum advantage, Danish filmmaker Thomas Vinterberg’s The Celebration is an unsettling, excited, often crazed, dark-edged comedy that gets decidedly bleaker as it goes, becoming an austere, unadorned tale of reprisal and justice-seeking.

When the patriarch of a large family, Helge (Henning Moritzen) throws a dinner party for his 60th birthday, one of his sons, Christian (Ulrich Thomsen) decides to confront him on a family secret with wild repercussions.

Christian, we discover, is in mourning over the suicide of his twin sister, and blames dear old dad, and his tell-all toast in front of the assembled guests gets uncomfortable fast. In the skilled hands of Vinterberg, family decorum and civility crumbles with abrasive, audacious excitement. The Celebration ain’t no pity party, instead it’s gleeful subversion at it’s very best.

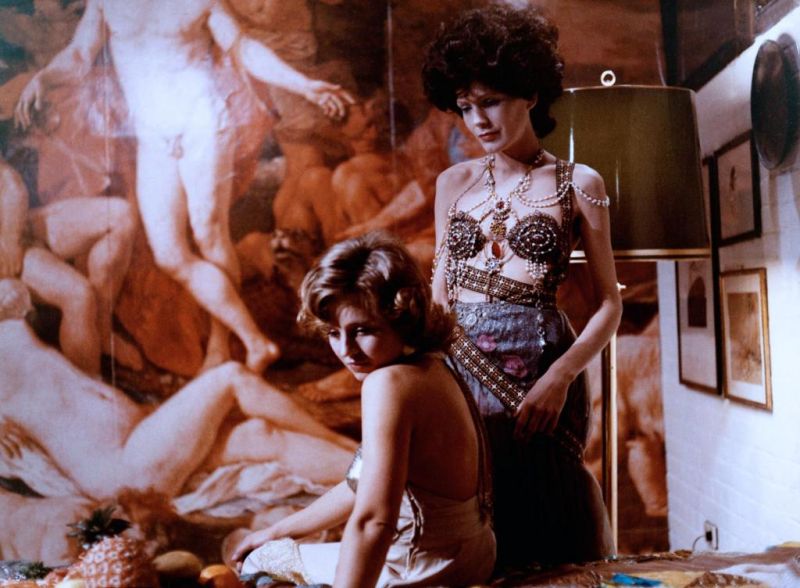

4. The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1972)

Cinematic dissenter Rainer Werner Fassbender was at his most controversial with this baroque, stylish account of sadomasochistic jealousies and jubilations between three lesbians in The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant.

While many pundits viewed the film as the apex of gay male misogyny (it’s New York City premiere was picketed by lesbian groups), the film more accurately pays homage to the florid and many hued melodramas of Douglas Sirk while also abutting Fassbender’s experimental theater origins.

The all-female cast, led by Margit Carstensen, is luminous, and Michael Ballhaus’ cinematography brilliantly reflects their restlessness. Fassbender’s screenplay, utilizing a four act plus epilogue structure, makes for a psychodrama of splashy ascendancy and intellect.

3. The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928)

“You cannot know the history of silent films unless you know the face of Renee Maria Falconetti,” wrote Roger Ebert, on this iconic screen legend. “To see Falconetti in Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc is to look into eyes that will never leave you.”As the martyred warrior-maiden, Falconetti is a force of nature, and Dreyer’s film is the quintessence of cinematic portraiture.

Dreyer pulls no punches as he explores ideas of faith and spirituality, portraying cruel characters—judges, scholars, theologians, holy men—made ugly by their bigotry, chauvinism, and skepticism. Nearly ninety years old, The Passion of Joan of Arc remains an arresting peculiarity of European cinema.

2. Persona (1966)

An actress, Elisabet Volger (Liv Ullman), suffers a breakdown wherein she retreats into silence, refusing to speak, she recuperates in a country cottage in the charge of a nurse named Alma (Bibi Andersson) in Ingmar Bergman’s preeminent film, Persona.

As an assuredly elusive on identity, remembrance, and human nature, this film stands as one of the most sustained philosophical explorations into the mystery of the human face, into psychic vampirism, and, strangely, into symmetry.

Considered by critics to be one of the 20th century’s most enduring works of art, Persona has influenced a diverse faction of filmmakers, from David Lynch and Woody Allen, to Olivier Assayas and Robert Altman, as well as being the screen debut of Ullman, Bergman’s greatest muse and collaborator. A challenging film, to be sure, it’s also a visually arresting, emotionally exacting, and unforgettable encounter with the very spirit of truth and it achieves something close to grace.

1. Rear Window (1954)

“We’ve become a race of Peeping Toms. What people ought to do is get outside their own house and look in for a change,” quips Stella (Thelma Ritter), a home-care nurse to a temporarily wheelchair-ridden L.B. “Jeff” Jefferies (James Stewart), in what amounts to the ultimate experience in voyeuristic cinema, Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window.

Apart from being a masterful slow-burn suspense thriller, Rear Window also approximates a surprisingly bad-tempered but no less brilliant study of contemporary society. As Jeff recovers from his injuries he wrestles ennui in his Greenwich Village apartment, where his titular rear window opens onto a wondrous view of the courtyard and numerous apartments in his building’s complex.

Jeff, and the audience by proxy, is soon swept up in a nosing spy game as he witnesses, amongst other things, a potential murder. Hitchcock manipulates the viewer to a dizzying degree, making one question what they’ve seen, while slyly hinting at a great many moral divisions, from feminist protocols, social conduct, and the etiquette of neighbors, even notions of misandry, and heroism, not to mention a ravishing turn from Grace Kelly as Jeff’s much younger, perhaps wiser, girlfriend, Carol.

François Truffaut once noted that “[Rear Window]’s construction is very like a musical composition: several themes are intermingled and are in perfect counterpoint to each other — marriage, suicide, degradation, and death — and they are all bathed in a refined eroticism,” thus detailing how the film, like the tenants across from Jeff, contain clandestine and diversified intentions, some healthy, some sinister, all engaging and with much hidden beneath the surface.

A major work from a master filmmaker, Rear Window is emblematic of Hitchcock’s best work, and is an enduring and time-honored classic.

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.