15. Humanité (1999)

Gorgeously photographed in CinemaScope, Bruno Dumont’s gritty, gruesome and controversial Humanité was his award-winning second feature (after 1997’s The Life of Jesus), widely considered his masterpiece. Starring non-professional actor Emmanuel Schotté as a police detective investigating the brutal rape and murder of a young girl.

Functioning primarily as a metaphysical detective yarn, Schotté portrays the seemingly autistic Pharaon de Winter, a provincial detective who longs incessantly for his young neighbor (Séverine Caneele). Both Caneele and Schotté rightly received the acting prize at Cannes in 1999 for their stunning, graceful and compassionate performances.

Powerhouse performances aside, part of what makes Humanité so artful and amazing is its painterly close-ups and long shots of idyllic and rural countryside damaged by darkness and death.

An austere and quasi-realist spectacle, Humanité’s transcendentalist overtones offer Dumont a distinctive auteur title, and is an unmissable movie for genre fans and arthouse enthusiasts. A dark but designful gem.

14. Farewell, My Lovely (1975)

Dubbed “the soul of film noir” by Roger Ebert, Robert Mitchum is marvelous as Raymond Chandler’s beloved detective Philip Marlowe in Farewell, My Lovely.

An oldfangled and nostalgic air permeates throughout director Dick Richards’ (Death VAlley) film, a superbly constructed pulp undertaking in finely-tuned noir thriller dress. Intelligently recalling vintage 1940s cinema and sticking true to Chandler’s original story of Marlowe’s helping sympathetic thug Moose Malloy (Jack O’Halloran) find his old flame.

The knockout cast includes a smouldering Charlotte Rampling as Helen Grayle and a baby-faced Sylvester Stallone in a bit part as Jonnie, the hired muscle. The moody, atmospheric reading of Los Angeles’ underbelly, ably reinforced by John A. Alonzo’s tight lensing — which reveres classical shadowy, smoky impressionistic film noir techniques — is a loving tribute to Chandler’s milieu and the detective genre in general.

13. Zodiac (2007)

David Fincher, with Zodiac, arguably presents his first real masterpiece and by the very nature of the project, confounds our expectations, presenting a story lacking closure but is still incredibly gripping all the same. Based on the harrowing true story of the ill-famed serial killer and the protracted manhunt he roused that ultimately lead nowhere.

Jake Gyllenhaal is San Francisco Chronicle political cartoonist Robert Graysmith – upon whom’s non-fiction book of the same name the film is based – who may just have figured out a way to crack the encrypted letters that the Zodiac has been taunting police and media with, pertaining to his past and future crimes.

Gyllenhaal is mesmerizing in his role, and leads a substantial ensemble cast that includes Robert Downey Jr. as crime reporter Paul Avery and Mark Ruffalo as SFPD Inspector David Toschi. Also rounding the A-list cast are Brad Pitt, Brian Cox, Elias Koteas and Chloë Sevigny.

For all its shaggy-dog digressions, Fincher shows an amazing amount of stylish restraint in what’s quantifies as a startling, discomfiting, troubling, and full bloom tour de force.

12. M (1931)

Based on the real life manhunt for a Düsseldorf childmurderer, Fritz Lang’s (Metropolis) first sound film is both an analytical and radical dissertation on authority and law. Peter Lorre’s performance is nothing short of extraordinary as child murderer Hans Beckert, and the role quickly established him as something of a cinematic icon.

Dogging Beckert’s trail is Inspector Lohmann (Otto Wernicke), desperate to catch the scourge plaguing his city for the last eight months. But Lohmann’s not the only man bent on identifying and bringing the murderer to justice. The bolstered police presence has put scads of pressure on the underworld and the black market, causing the formation of a crime syndicate, “The Ring” to track down the killer so that they can return to their shady practices without fear of John Law.

Lang’s contemporary setting and realistic milieu in M was quite incendiary and effective at the time, adding an element of complexity and social commentary that was largely absent in cinema, and certainly the subject matter and sadistic plot elements rattled censors and sensitive theater goers like little else that came before it. Mob rule, the legal system and morality were just some of the themes Lang skewered and dissected in Lang’s murderous masterpiece.

11. The Long Goodbye (1973)

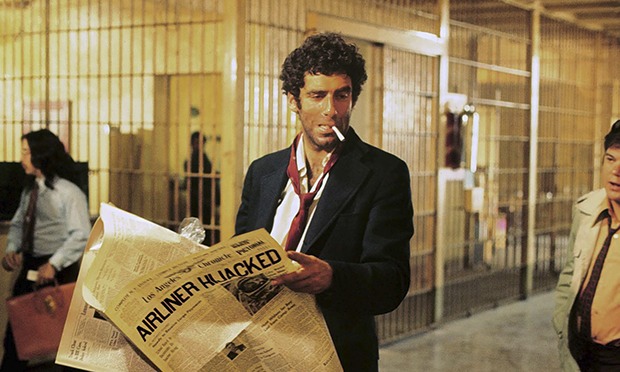

This inspired Raymond Chandler adaptation ranks amongst Robert Altman’s best, believe it or not, as Elliot Gould plays Philip Marlowe, placing our hardboiled private eye in 1970s Los Angeles.

Gould is great, radiating his own brand of existential cool in the role, presenting Marlowe as a chain-smoking, cat-loving, compulsive verbalizer. Altman assigned a Rip Van Winkle accession to the well-loved detective, as if he awoke 30 years out of date, in a world that no longer needs him.

Marlowe, hence given a fatalistic mind, is constantly trying to convince himself, and the audience, that he exists, despite the disdain evidenced all around him, that the world is moving on, tossing him and his antiquated profession to the curb, rather unceremoniously.

As with Altman’s best work – and the 70s was one hit after another for him – his fearless camera uses frequent pans, zooms, tilts, dollies, and cranes, consistently crashing with energy, and the feeling of improvisational spontaneity, wedded perfectly with the jazzy Johnny Mercer and John Williams score.

The Long Goodbye presents celebrity-obsessed cynicism, smart aleck-y sneers, neo-noir despair, explosive bouts of violence, and pitch-dark comic relief that even today feels incredibly modern. A minor masterpiece from one of the most exciting eras of American cinema.

10. Laura (1944)

A pivotal scene in Otto Preminger’s Laura finds police detective Mark McPherson (Dana Andrews) fast asleep in the titular Laura Hunt’s (Gene Tierney) apartment, underneath her haunting portrait, to be precise. Mark awakens, stirred by a presence that’s entered the room, but who it appears to be, well, that’s just not possible, Laura’s dead, isn’t she?

Leading men in film noir often become obsessed with a femme fatale, their downfall made imminent, and this idea is not eschewed in Preminger’s classic film. Narrated by newspaper columnist Waldo Lydecker (Clifton Webb), Laura recounts the sordid, strange tale of Ms. Hunt’s confounding death, by shotgun blast to the brain, and the police department’s investigation, in this classic, lush and dreamy black-and-white film noir miracle.

Pauline Kael referred to Laura as “everyone’s favorite chic murder mystery”, it was also a favorite film of the Cahier du Cinema directors, all of whom would shortly afterwards erupt as the French New Wave. Rarely does pulp fiction pedigree come across as flashy, or as hard to forget as Laura.

9. Vertigo (1958)

James Stewart is astounding and despicable as neurotic San Francisco police detective John “Scottie” Ferguson in this surprisingly cynical take on obsession.

As his psychological instability takes the thrust of the narrative – a tactic that initially alienated audiences and even Hitchcock devotees – focusing instead on his guilt and exploitation angle instead of the wandering wife/suicide case he started out on. Scottie, who possesses a paralyzing fear of heights, turns in his badge after a routine case results in the death of a fellow officer from a fatal fall.

Hitchcock chose to eschew studying suspense and instead zoomed in on themes of identity, unhealthy obsession, phobia, and sexual desire as Scottie falls for a suicidal dream girl, Madeline Elster (Kim Novak). Voyeurism, guilty conscience, doppelgänger duplicity, and wry humor add to the aloof mystery behind what many consider to be Hitchcock’s crown jewel.

8. The French Connection (1971)

Then unknown actor Gene Hackman gives a crowning performance as NYPD narcotics bureau detective Jimmy “Popeye” Doyle – netting Hackman an Oscar for his performance and shooting him to the A-list – in William Friedkin’s astonishing police procedural, The French Connection.

So assured and astonishing was Friedkin’s direction that he too took home an Oscar (the film received a total of five Academy Awards) in a fictionalized but frequently factual account of a landmark law enforcement victory that found two detectives mired in fieldwork bust a deal involving a 112-pound heroin sale.

It’s a gritty, pessimistic and unforgettable affair, with set pieces full to bursting with fist-pumping élan including one of the greatest and most gobsmacking car chases ever wed to celluloid as Popeye careens the wrong way down a one-way street at rush hour underneath elevated train tracks. It’s a “movie moment” with almost no peers, pure adrenaline, it doesn’t allow the viewer a second to catch their breath.