8. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (Robert Wiene, 1920)

In 1920, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari emerged as a pioneering piece of expressionist cinema that provided a mirror to the soul that the post-war German audience could not deny.

Recounted as a frame story from the perspective of Francis, the film tells the story of a crazed hypnotist named Dr. Caligari who directs a somnambulist to kill innocent people, allegorizing the way the German authorities sent the common man to commit murder. While the twisty story is itself innovative (the film is famous for one of the first twist endings in cinema), the twisted look of the film is the reason it has endured.

Famous for its visual style, achieved by its experimental set design and use of light and shadow, the film successfully conveys a sense of threat and anxiety to the viewer, who is forced to both react to this deranged world and question their own reality. In Caligari, the sets are painted, providing a deliberately unrealistic two-dimensionality. The scenery is filled with striking and invasive objects such as jagged trees and crooked windows.

The architecture is often curved and impossible within Francis’ flashback, but certain expressionistic remnants remain even at the end of the film, such as the elongated staircase of the asylum. The only public alternative to the restrictive asylum is the chaotic fair, marked with dizzying lights and looping rides, a symbol of the hectic modern urban experience.

Ultimately, the disorienting style of the film suggests that something imagined can be worse than something real. A precursor to film noir, this landmark silent film remains a visual phenomenon and holds up to this day.

9. Office Space (Mike Judge, 1999)

Based on Mike Judge’s own cartoon series Milton, the 1999 film Office Space has developed into a cult favorite, familiar to anyone who works at a desk. From its outset, in which the main characters drive through bumper-to-bumper traffic, the film plunges us into the frustration of the 9-5 workplace.

Peter, Michael Bolton (not that Michael Bolton), and Samir work at Initech, a soul-sucking IT company. After an epiphany prompted by the death of his occupational hypnotherapist, Peter decides to just stop showing up to work. With the help of his two friends, who learn they are about to be laid off, Peter devises a scheme to take something in return for the countless, mind-numbing hours they spent at Initech.

Mike Judge’s white-collar environment is at once absurdist and painfully familiar, rife with infuriating bosses, monotony, and passive-aggression. Yet it is the palpable combustibility of the film that always looms under its surface that keeps this story of workplace drudgery so fresh.

As incisive a satire it is, Office Space works doubly as an escapist adventure. Watching these three smash a stolen printer with a baseball bat hilariously juxtaposed against “Damn It Feels Good to Be a Gangsta” is as exhilarating as it gets.

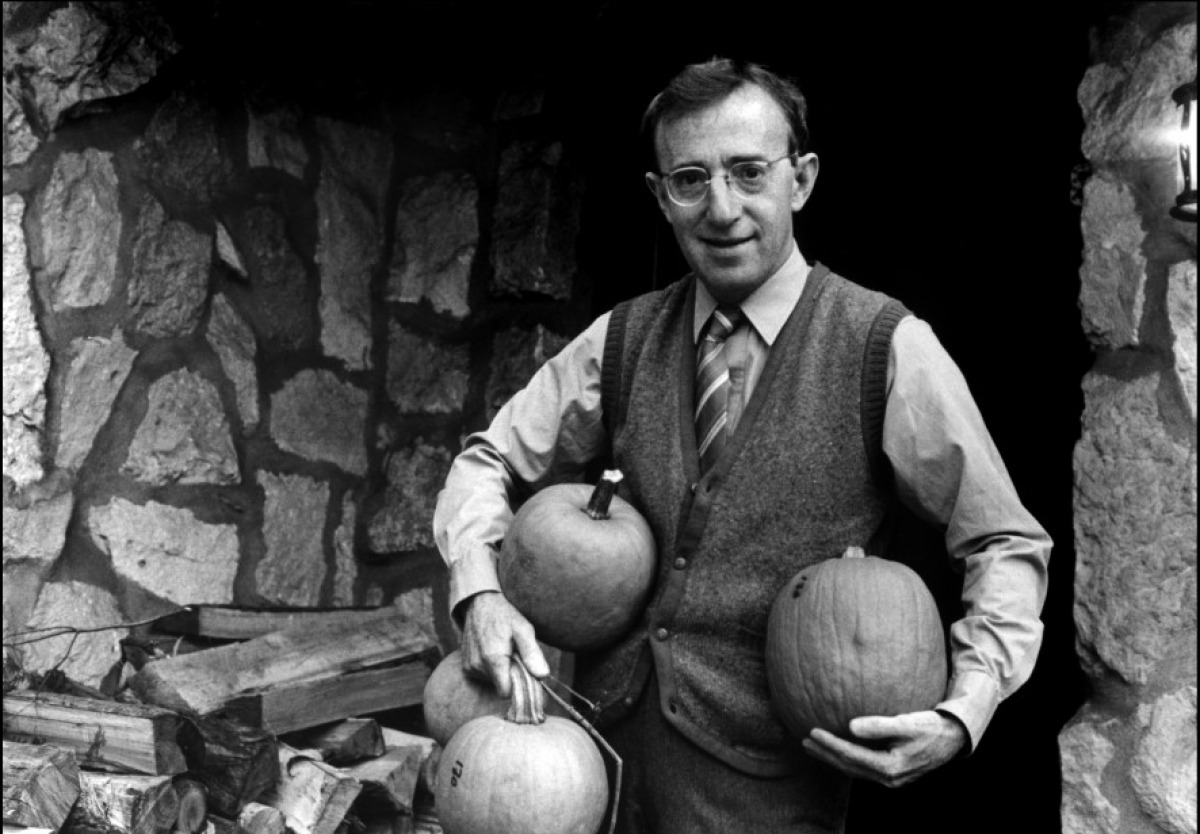

10. Zelig (Woody Allen, 1983)

Unfairly underseen, Woody Allen’s Zelig is a film that offers its fair share of laughs, but stands up as more than a trifle. A rare mockumenary made one year before This is Spinal Tap, the film recounts the life of Leonard Zelig, “the human chameleon,” a man born with the unique involuntary ability to blend into his surroundings.

Diagnosed as a protective mechanism by his curious psychiatrist, Dr. Eudora Fletcher, portrayed by Mia Farrow, Zelig instinctively acquires the behavioral and physical characteristics of those around him. Allen manipulates stock footage expertly to situate his character in some of the most iconic settings of his favorite time period, the Roaring Twenties, beginning beside F. Scott Fitzgerald before moving to Yankee Stadium to play alongside Babe Ruth.

In this way, the film comes across as a more piercing Forrest Gump. Zelig warns of the dangers of mass conformity and explores the dangerous phenomenon of celebrity, as Zelig transitions from national sensation to enemy.

Like many of his other films, Zelig is a film about neurosis, but expands on this theme to an uncomfortable extreme. Racked with anxiety, Leonard Zelig protects himself by becoming whoever surrounds him no matter how vile they are. Never settled and constantly on the move, Allen’s character resembles an updated version of the Wandering Jew.

At a young age Zelig’s desperate desire to assimilate is driven by anti-Semitism; the same desire ultimately leads him to blindly accept Nazism. While Allen’s film is full of his patented one-liners and witty gags, its message is troubling and lasting.

11. Passenger (Andrzej Munk, 1963)

Due to the untimely death of its director Andrzej Munk in 1961, Passenger was never completed as it was intended. Still composed of fragments, the film was released in 1963 with an explanatory voiceover. The film tells the story of the relationship between a female SS officer named Liza and an inmate of Auschwitz named Marta.

Passenger’s main issue revolves around neither politics nor ideology, and instead shows interest in examining these two women and interrogating what they remember and what they do not. Lacking the ideological bias that plagues many similarly themed films, Passenger leaves us with ambivalence and a sense of the undetermined nature of reality.

Passenger builds it present and forges its future on the basis of a particular understanding of the past; it is the elasticity of memory that protects Liza. Though she was in command at the concentration camps, every violent interaction shown in Passenger is consigned to the corner or the background of the scene and the frame.

Although the real-life setting of Auschwitz is ghostly, the more pronounced violence in the film is the disruption of the personal relationship between Liza and Marta. As Liza learns, the more you know someone, the greater you can punish them. Because Liza knows Marta’s intimate secrets, her actions seem all the crueler to us. We are challenged by the possibility of intimacy and violence going hand in hand.

Passenger is most fascinating because of its appropriately unfinished ending. Those who ended up releasing the film do not try to predict or hijack Munk’s vision, but instead attempt to grasp at and convey some of the questions Munk was interested in. Munk did not survive to finish filming the yacht scenes that take place in Liza’s present, but the film might in fact be better this way.

Alternatively, a series of freeze frames that delineate Liza’s narration keep her present literally fixed in time, and to that effect, entirely uninhabitable. Instead, only Liza’s past comes alive, enlivened by her memories.

12. The Lady From Shanghai (Orson Welles, 1948)

Perhaps Orson Welles’ most underrated film, The Lady From Shanghai is an unexpectedly satisfying and bizarre noir. Welles plays Michael O’Hara, a sailor sporting a memorable, if unconvincing, Irish accent. After saving a woman from a curious attack in Central Park, O’Hara is persuaded to hop aboard the luxury yacht owned by her husband, a wealthy and suspicious lawyer named Bannister. The titular lady, Elsa, is played by a blonde Rita Hayworth.

The film is infamous for being shot while Welles and Hayworth were in the process of separating in real life. This intriguing connection contributes to the murky sense that something is wrong, which penetrates the film from its outset, anticipating the oozing uneasiness of a film like Chinatown.

The original cut of The Lady From Shanghai was 150 minutes. Having been edited down by almost an hour, the film’s eccentric plot risks becoming impossible to follow. But the messy and convoluted nature of the story somehow works within its context of weirdness.

Welles succeeds in creating a mouth-watering dreamlike atmosphere, filled with sinister flavor, exotic locales, and vibrant imagery. The film’s famous final sequence in an abandoned hall of mirrors is a crackling visual sensation, essential viewing for any cinéphile.

13. Locke (Steven Knight, 2013)

Easily confused as an overlong BMW advertisement, Locke works as an emotional and thought-provoking character study of a man who is faced with the consequences of his actions, forced to delicately balance his personal and professional life.

Written by Steven Knight, who is known for writing Dirty Pretty Things and Eastern Promises, as well as creating Who Wants To Be a Millionaire, Locke tells the story of Ivan Locke, a construction foreman who is driving 163 kilometers from Birmingham to London on an improbably conflict-ridden night.

Mere hours before he is supposed to conduct the largest concrete pour of his life, Locke is on his way to a hospital where a woman with whom he shared a one-night extramarital affair is about to give birth.

Over the course of the two hour ride, he must own up to what is the greatest mistake of his life to his wife (“The difference between once and never is the difference between good and bad”), talk his son through their favorite team’s football game, and counsel his coworker Donal through the construction job at hand.

Balancing composure with intensity, and speaking in a hypnotizing Welsh accent, Tom Hardy delivers a tour-de-force performance. And as strong as Hardy is, the rest of the film’s cast, reduced to voices off-screen, is equally stellar. As Knight alternates between close-ups and medium shots from all angles, the tension escalates but the ride retains an unnerving sense of calm at its constant pace of 80 kilometers per hour.

Despite the extreme constraint Knight deliberately places upon himself, Locke lives up to its clever conceit. The unconventional road movie is able to sustain its suspense over the course of 86 minutes because of the depth of thought given to its central character’s ethical compass. Never before has concrete been so compelling.

14. Shoot the Piano Player (Francois Truffaut, 1960)

Based on David Goodis’ short novel, Shoot the Piano Player is a delightful amalgam of American crime fiction and French New Wave filmmaking. Partly in response to the success of The 400 Blows, Francois Truffaut hoped to deliver something new with Shoot the Piano Player.

As Truffaut puts it, “The idea behind Le Pianiste was to make a film without a subject, to express all I wanted to say about glory, success, downfall, failure, women and love by means of a detective story. It’s a grab bag.”

Defying categorization, the film is both an ode to American noir and a staple of the Nouvelle Vague, filled equally with comedic and tragic elements. Perhaps this is the reason that the film did not enjoy immediate success. But this combination makes Shoot the Piano Player a fascinating and generous film that offers plenty of rewards.

Charles Aznavour plays a reserved pianist, who gives up a promising career after his wife commits suicide, choosing to play piano in a dive bar under an alias in an attempt to forget his loneliness and withdraw from the world. Using flashback, voiceover and a murderous subplot, Truffaut quotes from film noir and his hero Alfred Hitchcock. But Truffaut still privileges spontaneity and never forgoes having fun with his film.

Perhaps out of his own boredom, Truffaut makes a comedy of the film’s gangster characters, freely juxtaposing slapstick humor against thrills. Up through its exhilarating shootout finale, Shoot the Piano Player is full of unexpected delights.

15. The Only Son (Yasujiro Ozu, 1936)

Despite the fact that The Only Son is Yasujiro Ozu’s first sound film, its dialogue is practically superfluous. Instead, Ozu’s frames speak volumes, conveying the love and sadness inherent within the film’s central relationship between mother and son.

The story, set alternately in the rural town of Shinshu and the bustling metropolis of Tokyo, follows a hard-working widow named Tsune, who strives to provide a respectable life for her son Ryosuke. The simple story maintains Ozu’s familiar style, relying heavily upon static shots that are each carefully conceived and artfully composed.

When his mother sends him off to school, Ryosuke vows to become a great man. Years later, after Ryosuke has moved to the urban landscape of Tokyo, Tsune pays her beloved son a visit. It is unclear that he has lived up to his vow.

The Only Son exhibits Ozu’s attention to and appreciation for details: the composition of the shot of the mother ands son eating dinner with his baby asleep in the foreground, the camera following Ryo’s hat when he drops it down in frustration, Tsune turning away from her friend when she tells her, with not enough certainty, that her son has become a great man. All this makes for an engaging and graceful film.