16. Stranger Than Paradise (Jim Jarmusch, 1984)

The films of Jim Jarmusch virtually exude coolness. Stranger Than Paradise is no exception. Winner of the Caméra d’or at the Cannes Film Festival in 1984, his second feature after Permanent Vacation ultimately proved to be a definitive film in the American independent film landscape. John Lurie plays Willie, an irritable Hungarian-born New Yorker who would rather not have to put up his cousin Eva (Eszter Balint) who is visiting from Budapest.

With the help of his lovable loser friend, Eddie (Richard Edson), Willie helps Eva get acquainted with the America through its cigarettes, comic books, and TV dinners alike. While there is little action, the film is broken up into three parts.

Although they proceed chronologically, they are practically interchangeable. While the characters move from New York City to Cleveland to Florida, the drab settings are indistinguishable and the characters’ boredom is never relieved. When Eddie hears that Eva is moving to Cleveland, he calls it a beautiful city despite having never having been there. When he finally gets there, Eddie puts it, “You come to some place new and everything looks just the same.”

It is hard to put your finger on what exactly makes Stranger Than Paradise so compelling. The settings are stark and unadorned. The narrative is driven by style, not plot. But miraculously, even in a film about relentless ennui, Jarmusch demands your close attention.

Every single shot in Stranger Than Paradise fades to black before a new one begins. We are thus attuned to a series of vignettes, each beautifully filmed in a single take. In Stranger Than Paradise, Jarmusch makes a whole lot out of nothing. In other words, he puts a spell on you.

17. Ida (Pawel Pawlikowski, 2013)

The winner of the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 2015, Ida is director Pawel Pawlikowski’s first Polish film, having immigrated to England when he was 14. Only when he was in his late teens did the Catholic Pawlikowski learn that his paternal grandmother was Jewish and had been murdered in Auschwitz. Presumably this is where Ida’s story of second-hand identity originates.

The film starts in a convent. Young novice Anna (Agata Trzebuchowska) is set to take her vows, but is first instructed to meet her aunt in Lodz. There, Wanda (Agata Kulesza), a stylish and cynical judge almost delights in bluntly informing her niece that her real name is Ida Lebenstein and she is Jewish. The three words, “You’re a Jew,” set the stage for an unlikely road movie and an emotional internal investigation.

Anna embarks upon a journey with Wanda to find where her parents remains; their trip doubles as a haunting foray into the past for both characters. In stunning displays of acting, they meditate on their tragedies in different ways that both demand our contemplation. Ida deals with sensitive themes that are undoubtedly pertinent to the entire country of Poland, but does so with utmost care and consideration.

One of the most beautifully photographed films of the last decade, Ida is exquisitely framed and filmed in sharp and beautiful black and white. Some of the shots of drab rural Poland and of the urban cool in its jazz clubs even recall Jarmusch’s work in Stranger Than Paradise.

Making wonderful use of the constraining and claustrophobic Academy ratio, Ida has us constantly feel the burden on top of the film’s characters. Measured pacing allows the film to unfold patiently over the crisp 80-minute runtime. Silence in the film is a virtue, allowing us to stare intently at the beautiful and emotional frames. But the silence is also deeply sad, as it represents a population lost and an identity shattered.

18. Following (Christopher Nolan, 1998)

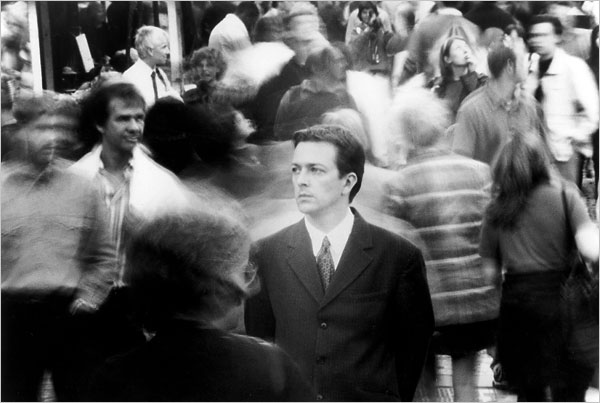

Before his landmark Memento, Christopher Nolan made Following, a micro-budget 70-minute thriller. The film marks Nolan’s first foray into non-linear narrative. Beginning in typical noir fashion, we hear the film’s protagonist speaking in voiceover. He tells us, “The following is my explanation… well my… my account of… well, what happened.” Moments later we find out that we have been tricked. Bill is not speaking to us, but rather to a police inquisitor.

And only then does the opening line reveal its pun. The film’s protagonist Bill (Jeremy Theobald) is an unemployed writer who becomes obsessed with shadowing strangers, following them for the ostensible purpose of gathering material for his writing. When Bill follows a burglar named Cobb, he gets swept up in his underworld.

From that point on, Nolan’s voyeuristic premise takes copious twists and turns. Anticipating his much acclaimed follow-up Memento, Nolan boldly jumps back and forth in time. He escalates the uneasiness of the film between its parallel timelines by alternately providing and withholding information from the viewer.

Filmed in gritty 16mm black and white, Following is an irresistible thriller. While its modest budget and tight storyline distinguish it from Nolan’s more prominent and grandiose later efforts, the director’s confidence and craft is at full display from the outset.

19. Before Sunset (Richard Linklater, 2004)

In an act of tremendous patience that proved not to be his last, Richard Linklater waited nine years to follow up his 1995 romance Before Sunrise. Delightfully minimal, its unconventional sequel, Before Sunset whips by at only 80 minutes. This time set in Paris, Linklater reintroduces us to Jesse and Celine, played years after their whirlwind romance in Vienna. Jesse is in Paris to read a passage from his successful new book.

As he clumsily answers questions about whether his book is autobiographical, memories of Jesse and Celine’s own brief encounter flurry on the screen. Over the course of the next hour so, it is our privilege to be in company with the couple and they stroll around the beautiful streets of Paris and catch up.

The film takes its time, letting the two slowly reveal the changes in their lives since their last meeting. The two have grown up, lending the film a sense of maturity and a tinge of sadness. In a display of directorial confidence, Linklater shoots the conversation in long takes that last up to 11 minutes.

Tellingly, Linklater shares screenwriting credit with Hawke and Delpy, who demonstrate naturalness and nuance in their acting. Filmed only in 15 days, this is the simplest and arguably the strongest entry of a trilogy notable for its minimalism.

20. The Color of Pomegranates (Sergei Parajanov, 1969)

Sergei Parajanov’s 1969 film The Color of Pomegranates, which was called Sayat Nova before the film was banned in Armenia, is an unmatched cinematic experience. The film loosely tells the life of Armenian poet Sayat-Nova. Abstaining from a literal approach, the film begins by noting that, instead, “the film maker has tried to recreate the poet’s inner world.”

Using painterly tableaux, Parajanov lets his expressive images speak for themselves. Especially memorable are shots of pomegranates being smashed, a man with a peacock’s beak in his mouth, and a boy swinging from a tower.

Unlike many of the other films on this list, Parajanov’s film feels much longer than its 78-minute runtime. It takes its time and appreciates stillness. The quote repeated throughout the film, “The world is a window and I am tired of these arcs,” encapsulates its sentiments and shows its emphasis on architecture and composition. The repetition of this quote and of the shots of the young boy create a sense of retrospection and fatigue that builds the enduring, slow, and thoughtful tone of the film.

21. The Kid With a Bike (Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, 2011)

The Kid with a Bike is a typically devastating slice of life story made by the consistent Dardenne Brothers. Bearing obvious influence to De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves, the film tells the story of Cyril, a young boy of 10, whose troubled upbringing in foster homes is grounded by his attachment to his bike. Cyril’s unrestrained innocence is the source of physical and emotional pain. Constantly moving, Cyril uses his bike to move forward and escape from his problems.

When Cyril catches another boy riding his bike, Samantha, the owner of a local beauty shop, buys back the bike and returns it to Cyril. The real tragedy is that the bike was not stolen, but rather sold by Cyril’s absentee father.

Played by Cecile de France, Samantha eventually becomes Cyril’s foster mother and the film’s emotional heart. Scared to accept Samantha’s love, Cyril is vulnerable and imperfect. In the film’s unpredictable second act, Cyril’s propensity for getting himself into trouble has dramatic consequences.

The film, which has the feel of a naturalistic fairy tale, is intimate and affecting. Free-wheeling camerawork follows Cyril, always dressed in bright red, wherever he goes. In The Kid with a Bike, the Dardenne Brothers interestingly use non-diegetic music for the first time, in the form of brief swells that capture the tender emotions of the boy. At only 87 minutes, the film is economical and direct. Despite its simplicity, the story of love and self-preservation is ultimately devastating.

22. Brief Encounter (David Lean, 1946)

The appropriately brief Brief Encounter is David Lean’s last collaboration with writer Noel Coward. Sometimes called the British Casablanca, Brief Encounter is not saccharine, but is powerfully romantic. The film begins at the end of an affair between a housemaid, Laura, and a married doctor, Alec (Celia Johnson and Trevor Howard), before they go their separate ways.

Although we do not know it yet, the two have just spent several heartfelt weeks together and have formed a rare connection. Uncommon for films that broach the subject of infidelity, their actions are not treated as malicious but instead are considered sympathetically. The relationship between Laura and Alec is all the more affecting because of their ordinariness.

As Laura points out, “I didn’t think such violent things could happen to ordinary people.” The unconventional love story would become clear inspiration for the chance encounter between Jesse and Céline in Richard Linklater’s Before Sunrise, which restages the tie between railways and fleeting affairs.

While Brief Encounter is based on a play, the classic film about unconsummated love is marvelously transformed on the silver screen. Its railway station setting thrives in starkly beautiful black and white, with its billowing smoke and dream-like shadows that would rival any film noir. Rachmaninoff’s melancholic Second Piano Concerto is repeated throughout, helping to deliver the film’s emotional message about the different directions one takes in life.

23. Videodrome (David Cronenberg, 1983)

David Cronenberg’s 1983 film Videodrome tells the story of man merging with machine. From the get-go, Howard Shore’s unsettling score begins over Universal’s logo. The film then introduces us to Max Renn, played with an articulate intensity by James Woods, the head programmer of sleazy cable station Civic TV.

When he comes across an ultraviolent torture show called Videodrome that promises to be the next big thing in television, he is swept into a delirious spiral of conspiracy, hallucination and body horror. Inspired by the works of media scholar Marshall McLuhan, Videodrome depicts how video technology shapes not just our contemporary culture, but also our minds and bodies. The film becomes near impossible to follow, but by its conclusion has us rooting for “the new flesh” nonetheless.

In Videodrome, Cronenberg first warns of the overstimulation and desensitization caused by the narrowing distance between ourselves and technology. Cockily, he then proceeds to provoke us with unrelenting and shocking sex and violence. Using meticulously crafted physical effects, Cronenberg creates indelible graphic images that fuse man with machine and blur hallucination and reality.

Who can forget Max Renn submerging himself into a pulsating and protruding television set through his sadomasochistic girlfriend’s analog lips? Or Renn yanking a pistol from a VCR-shaped hole in his torso for that matter? Videodrome is unquestionably grotesque. But it is a wildly fun and subversive triumph of grotesquerie.