24. House (Nobuhiko Obayashi, 1977)

Looking at the unprecedented success of Jaws in the United States, House came out of an ambition to make a Japanese blockbuster for popular audiences. But Nobuhiko Obayashi would not only generate the thrills of Jaws, but also create a film unparalleled in its wacky horror.

The story itself tracks seven young girls, named for their character traits (Gorgeous, Fantasy, Kung Fu, Melody, and so on), who retreat to Gorgeous’ aunt’s house for summer vacation. The house proceeds to eat them one by one. And that’s about it. But the story alone will never do the film justice. House is an eccentric film shot in eccentric ways and must be seen to be believed.

The film is unapologetically bizarre, using deliberately unrealistic and distracting effects, cheesy music, and gratuitous gore. By indulging in countless cinematic tricks and expressive techniques, Obayashi crafts a flamboyant style entirely his own.

Both the stuff of nightmares and childlike glee, House largely owes itself to Obayashi’s pre-teen daughter Chigumi, who gave advice on what to include in the horror film. As a result, the film yields playful and enduring images of a piano which devours its player and an assault of cascading mattresses.

House both nods to the horror story archetypes that came before it and destroys them. The film is so whimsical, yet leaves us unsettled in our enjoyment. Words were never meant to explain House, it is a film best experienced, either laughing aloud or mouth agape.

25. Journey to Italy (Roberto Rosselini, 1954)

Over the course of the 1950s, Italian filmmaker Roberto Rossellini filmed several pictures with his wife Ingrid Bergman, creating roles distinct from her Hollywood persona. In Journey to Italy, she and George Sanders act together as Katherine and Alexander Joyce, an English couple in Naples to sell an inherited property.

Right off the bat, Rossellini drops us into a hectic drive in the foreign land, already facing obstacles along their path in the form of water buffalos. Starting on the move suggests that this is clearly not the beginning of the story. Yet only now, after eight years of marriage, do Katherine and Alexander realize they are strangers.

The Italian landscape becomes a character in itself that comes to reflect their deteriorating marriage. Alexander hates the country, dismissive of Italian laziness and constantly frustrated with his inability to communicate.

Katherine, on the other hand, grows sad and lonely. In an unforgettable sequence, the couple, on a visit to Pompeii, sees the plaster castings of human beings killed thousands of years ago by the volcanic eruption.

The powerful snapshot in times shows a man and a woman at the moment they died. Later, Katherine visits the haunting igneous lava fields of Vesuvius and ossuary of Pompeii alone with a tour guide. Shot artistically and with grace, Rossellini’s exploration of themes such as alienation and the temporality of man, manages to avoid coming across as heavy-handed.

The film’s ending echoes its beginning. The couple is impeded once again, this time by a parade. This time however, Katherine gets whisked away by the masses. This unexpected separation almost by miracle sparks an epiphany of sorts that keeps the two together upon their reunion.

26. Daisies (Věra Chytilovà, 1966)

Intercutting a clip of wheels turning with an explosion, Daisies begins with interruption, establishing a pattern that will not cease across the film’s 74 minute running time. Directed by Věra Chytilovà in 1966, Daisies is a product of the Czech New Wave at its most playful and subversive.

The film follows two girls each named Marie, played by non-actors Jitka Cerhová and Ivana Karbanová, as they maneuver through a spoiled world. Considered a feminist film, the girls break from an initial paralysis, determined to be spoiled themselves. They are unabashedly sexual, engaging in consumption, exploiting older men. The destructive behavior of the girls is matched by Chytilovà’s formal destruction. The film revels in fragmentation and instability.

Taking influence from Surrealism and Dada, Chytilovà makes repeated use of collage, montage and jump cuts. In one memorable sequence, the two Maries dismember each other with scissors only to be recomposed. Breaking down gendered performances and cinematic prescriptions, Chytilovà freely shifts between color filters and experiments with framing to constantly have you view the film in a new light.

While today Daisies is known as a canonical art film, the film is also pure anarchic fun. As provocative as some of its images are, it works just as well as a strange comedy. After a cathartic food fight, Daisies ends with the words, “This film is dedicated only to those who get upset over a stomped-upon bed of lettuce.”

27. Titicut Follies (Frederick Wiseman, 1967)

Titicut Follies is the debut film of the prolific and legendary documentarian Frederick Wiseman, offering his first of many candid looks at America’s social institutions. Filmed at the Bridgewater State Hospital for the criminally insane, the contentious film only received limited release in 1967 and was subsequently banned by the state of Massachusetts.

As argued by Vincent Canby in his 1967 review, “its content dictates it style.” Without a voice-over, title cards or music, Wiseman deviates from more classical documentarian modes and instead embraces a verité style that is unflinching and hard to watch.

Titicut Follies provides a rare and intimate look into the daily life of the inmates. Some are catatonic, but we are allowed to listen to others and watch them perform in talent shows and stand-up routines. Without warning, however, these moments are intercut with painful sequences that show the inmates being mistreated by the institution’s staff.

Routinely they are force-fed, stripped naked, and tormented in a way that violently shakes our confidence in the institution. These scenes are often upsetting and heart-wrenching precisely because of the stark nature in which they are filmed by Wiseman and his cinematographer John Marshall.

Yet that is not to say that Wiseman plays no role in the power that this film holds over its audience. On the contrary, the terse and tough nature of the film owes itself to the way Wiseman edits his film, allowing his style to be dictated by the rare and concerning reality in front of him.

28. Rope (Alfred Hitchcock, 1948)

Celebrated for its clever camerawork, which gives off the illusion of the film being shot in one continuous long take, Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope is one of his shortest efforts. In Rope, the master of suspense confines himself to a dinner party. Seemingly in real time, the entire film takes place over the course of one evening in one apartment.

Influenced by the Leopold and Loeb case of 1924, the film begins by letting its viewers in on the perfect murder, a murder committed without malevolent intent, but rather for the sake of getting away with it. Motivated by Nietzchean philosophy of the ubermensch, the murder of David is committed by two of their old classmates, a sharp, pompous Brandon and a more reserved Phillip, played by John Dall and Farley Granger respectively.

As the dinner guests arrive one-by-one, there is no real doubt from the start that Brandon’s cockiness will lead to his ultimate downfall. Brandon deliberately uses the rope that he strangled David with to tie books for David’s father. David’s body itself is kept in the very chest upon which the dinner is served. Hitchcock’s morbid humor is expressed repeatedly in the clever wordplay, which continually alludes to the murder.

As the night progresses, Hitchcock’s experiments moving the camera are gleefully on display; the tension sizzles as the plan unravels. While the story itself is one of Hitchcock’s simplest, Rope is so playful and cleverly scripted that it has never been so much fun to watch a murder.

29. This is Not a Film (Jafar Panahi and Mojtaba Mirtahmasb, 2011)

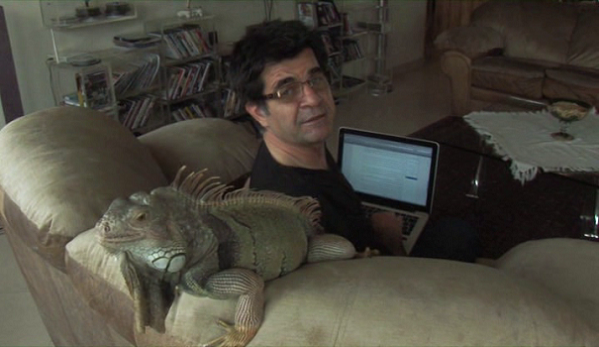

As is apparent by its title, This is Not a Film is quite different from the other selections on this list. The documentary directed both by Jafar Panahi and Mojtaba Mirtahmasb was made secretly while Panahi was under house arrest in his Tehran apartment as he appealed his sentence, which consisted of six years of prison and a 20-year ban from filmmaking.

Over the course of the last three decades, Iranian cinema has been characterized by rich expressions of universal humanity. After seeing This is Not a Film, the successes of Iranian directors such as Panahi are all the more impressive coming from within the suffocating and often demoralizing constraints of censorship.

The pressurized political environment comes across in the film as Panahi is practically forced to speak in code while on the telephone. Yet, while This is Not a Film is a defiant political statement by its existence alone, it is moreover a thoughtful reflection on filmmaking itself and an emotional look into Panahi’s life.

Jafar Panahi recruits the help of friend and documentarian Mojtaba Mirtahmasb to film him recounting a screenplay that never made it past Iranian censors. Watching Panahi’s intricate cinematic vision unfold on his living room carpet is both mesmerizing and heartbreaking. At one point, Panahi breaks down and refuses to continue narrating the film that is so obviously personal to him, asking, “If we could tell a film, then why make a film?”

This is Not a Film provides as clear an answer to that question as any other film you are likely to see. It is cinema devoid of all else, purely the need to convey a vision. In spite of all his restrictions, Panahi demonstrates the freedom of Iranian cinema that allows it to yield art.

When Mirtahmasb has to leave for the night, Panahi can no longer resist and takes the reins of the camera, turning it away from himself onto a student he finds coincidentally collecting his trash. The prolonged interaction in an elevator is amusing albeit unexceptional, but the circumstances behind it make it riveting.

30. L’Atalante (Jean Vigo, 1934)

The first and only full-length feature of Jean Vigo, a filmmaker whose life was tragically cut short at the age of 29, L’Atalante is often regarded as one of the greatest films of all time. The romantic story tells the tale of two newlyweds, Jean, a barge captain (Jean Dasté) and his beautiful wife Juliette (Dita Parlo), who take off on his boat “L’Atalante.” Filled with cats and dismembered hands, the boat is a comically tough place to adjust to married life.

Everything seems to be going wrong. Jean is overly protective and easily jealous. Juliette, on the other hand, feels restrained and wants desperately to experience the excitement of a city like Paris. When the tension between the couple reaches its boiling point, the two briefly separate. Only then do we feel the devastating power of their love.

The comic tale suddenly becomes deeply affecting and poignant. When apart, the pair dream of reconciliation from their separate beds in a stunning, sensual series of crosscut shots. As Père Jules, Jean’s heavily tattooed first mate, Michel Simon steals the show. His humor and humanity are contagious and lend a resonance to couple’s young marriage.

Through its stirring synthesis of the real and the fantastic, L’Atalante helped to usher the short-lived, but much celebrated Poetic Realism movement in French film. Throughout the film, Jean Vigo demonstrates his preternatural ability to produce beautiful, lyrical images.

In a famous sequence, Jean, tormented by having lost his newlywed, plunges himself off the barge into the water. After a few moments, Jean’s drowning face is dazzlingly superimposed with Juliette’s radiant smile, the one vision that can save his life. A few scenes later, Jean runs onto a beach in desperation. Instantly, it becomes clear that we are watching the genesis of Antoine Doinel in The 400 Blows.

Author Bio: Tarek Shoukri is a recent graduate of Brown University. He founded the Brown University Film Forum in 2013 and most recently served as the associate director of the Ivy Film Festival, the world’s largest student-led, student film festival.