Cinema is the only art form capable of utilizing and combining all other arts, and in such inspiring ways that it can produce a new way of complete human expression; ergo a fresh, and “sui generis” art itself. However, as in every art form, to achieve a confirmed or acclaimed artistic status is not a matter of self-declaration, but one of specific assets. Perhaps the most critical of all those assets in film is none other than the camerawork.

The camera placement and movement is one of the most crucial aspects in every film production. It represents the overall vision of the director, the skill of the director of principal photography, and their ongoing collaboration throughout the filmmaking process. Since the beginning of feature films in the first decade of the 20th century, many of the pioneering techniques have been used extensively, maximizing not only the possibilities of each era’s camera technologies, but also the level of artistry in motion pictures.

Tracking shots, crane shots, multiple cameras shooting the same scene from different angles, “Dutch angles”, long takes, the use of deep focus, the use of wide-angle and zoom lenses, and intentionally unsteady shots through a hand-held camera, are all different ways of making a film more beautiful, and more rich in meanings and symbolisms. Add to that the benefits of post-production (editing, special effects, soundtrack), and it is quite clear that cinema is limitless regarding its creative potency.

Any filmmakers who have mastered all those classic camera techniques mentioned above, and are lucky enough to have a well-written screenplay on their hands, plus an efficient crew to surround them, meet the requirements to make a good film.

But to make a great film, you need a bit of that extra magic that separates the true visionaries of the medium (those who challenge the audiences to follow them in their often uncompromising and non-mainstream cinematic ventures) from the dexterous craftsmen (those who depend on their technical expertise in order to impress the largest possible amount of viewers, incorporating the “entertainment” factor into their work).

As Aristotle quotes, “the aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance”. The following list is a selection of 30 movies (please do not pay much attention to their order, it is of secondary importance), from different eras, genres and cinema movements, which fulfill this aim by relying heavily on their brilliant camerawork. These are not necessarily revolutionary movies in terms of technological breakthrough, but they are in terms of artistic virtuosity.

30. City Of God (2002)

Directed by Fernando Meirelles, & Kátia Lund

Cinematography by César Charlone

One of the most poignant crime films of the 21st century thus far, “City of God” is a coming-of-age story which manages to point out the unstrained social commentary surrounding the recent history of Brazil’s organized crime.

The subjective narrative, freeze frames and sweeping scene shots are clearly influenced by the cinematography in Martin Scorsese’s “Goodfellas” (although director Fernando Meirelles uses a non-linear narrative style, plus many amateur actors from the favelas, which are also key elements for the depiction of the disordered lifestyle of the gangs), but César Charlone’s camera has a life of its own, fully dependent on the era in which the events take place; lively and furious in the late 60s, more static and character-centered during the majority of the 70s, and documentary-like in the protagonists’ more mature phase (the 80s).

29. Bande À Parte (1964)

Directed by Jean-Luc Godard

Cinematography by Raoul Coutard

A French New Wave gem, “Band Of Outsiders” is quite more accessible than Jean-Luc Godard’s previous contributions to the movement (“Breathless”, “Contempt”, “Vivre Sa Vie”), mainly because of the amusing narrative form, and the charming heist/love triangle plot.

For most of its running time, it is a carefree inner-city road movie, where the camera focuses on the “outsiders” while they drive, chat, dance and run all over Paris (there are three particular scenes which remain highly influential – if you are familiar with the dance scene in “Pulp Fiction”, you will definitely see the connection, in terms of style), providing a vibrant portrayal of the city life, and paying tribute to youthfulness at the same time.

28. Seven Samurai (1954)

Directed by Akira Kurosawa

Cinematography by Asakazu Nakai

This heroic samurai gathering is one of the most respected and influential movies of all time, and one of the few really convincing slices of life from previous centuries (Kurosawa and Tarkovsky are probably the greatest ever in that department).

There is no particular secret behind the film’s success, other than the creator’s persistence to take the most out of every situation. This translated to a constructed set on location from the start, in order to get the best performances out of his cast, and the innovative (at the time) use of multiple cameras for the action sequences.

27. Kes (1969)

Directed by Ken Loach

Cinematography by Chris Menges

“Kes” is arguably the best British drama of all time, the finest of all Ken Loach’s social realist films, and quite possibly the most beautiful film inspired by Italian Neorealism.

Chris Menges employs some long-distance shots to take advantage of South Yorkshire’s contrasting scenery. At one end, there is the beautiful green countryside (the place where a boy like Billy – the main star of the film – can enjoy some peace, away from the bullying at school and the quarrels at home), while at the other end, the quiet but depressing little towns, with a clear view of the nearby mines and industrial establishments (the most probable life destination for all the youngsters of the area). These images set the tone for what is about to come, while the use of non-professional actors speaking the Yorkshire dialect gives a documentary-like flavor to the film.

26. Apocalypse Now (1979)

Directed by Francis Ford Coppola

Cinematography by Vittorio Storaro

On the surface, this epic adventure may look like over-the-top war poetry, but in reality it is a thorough study of human nature.

Coppola (together with John Milius who co-wrote the screenplay) used the Vietnam War as the vehicle for his story, and shot the film in the Philippines. For the biggest part of the movie, the camera moves slowly and serves as Captain Willard’s point of view. His river journey into the jungle in order to spot and terminate Colonel Kurtz’s unauthorized operations, visually echoes Lupe de Aguirre’s search for El Dorado (Herzog’s “Aguirre, Wrath Of God” was a major influence on Coppola), but there are also a few surreal modern war sequences happening along the way.

25. Shadows Of Forgotten Ancestors (1965)

Directed by Sergei Parajanov

Cinematography by Viktor Bestayev, & Yuri Ilyenko

A “Romeo & Juliet” type of story, “Shadows Of Forgotten Ancestors” is a film with strong naturalistic elements and symbolism (one of the main reasons behind Parajanov’s condemnation to artistic death inside the Soviet Union).

The frenetic camera movement blends with intense colors, costumes and the unique folk music of the Carpathian Mountains, and the result is a sublime celebration of the Hutsul culture. This is a film that could have been made without any dialogue; the camera does the speaking, as we are witnessing a pure cinematic explosion of genius.

24. Le Plaisir (1952)

Directed by Max Ophüls

Cinematography by Philippe Agostini, & Christian Matras

“Le Plaisir” is an anthology of three dramatic short stories; all associated with pleasure, and a typical Ophüls masterpiece.

In each story, there are a number of virtuosic dolly shots of the basic characters’ gatherings, which give a romantic tone to the whole project. As for the first story in particular, though it’s the smallest one duration-wise, it remains astonishing even by today’s standards. It begins with extraordinary “Dutch angle” shots, which pave the way for the splendid long take of the dance hall scene, and the rest is history.

23. Down By Law (1986)

“Down by Law” is a black and white cult comedy classic by one of the most original American indie filmmakers, who was fortunate enough to have Robby Müller behind the camera, and a still-unknown Roberto Benigni in front of it (next to Tom Waits and John Lurie) speaking English. The result was a rare mix of surrealist humor and downbeat beauty.

Müller used slow-moving camerawork and natural day and night lighting, which were perfect fits for the three loners of the movie, the empty streets of New Orleans, and Waits and Lurie’s hypnotic soundtrack (both the composers and stars of the film).

22. Days Of Heaven (1978)

Directed by Terrence Malick

Cinematography by Néstor Almendros, & Haskell Wexler

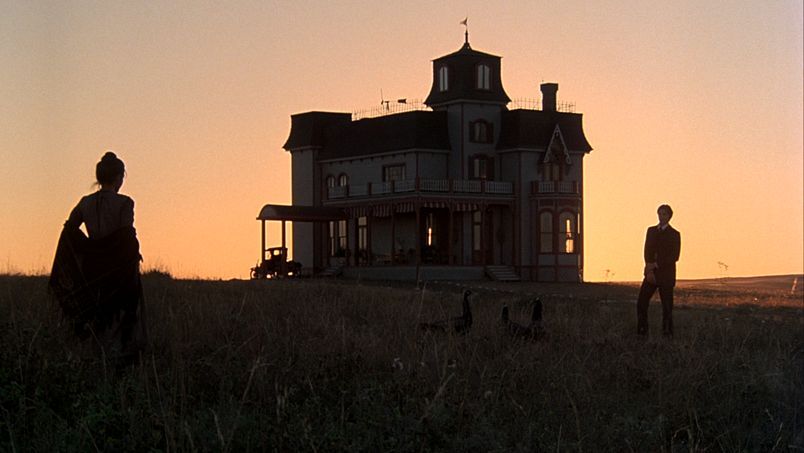

A period romantic drama set in the Texas Panhandle (the actual shooting location was the ghost town of Whiskey Gap, Alberta, Canada) and narrated from a little girl’s point of view, “Days Of Heaven” is one of the most notable examples of American arthouse filmmaking.

The images that appear onscreen are some of the most captivating ones in film, and Malick’s stubbornness to shoot daily during the “magic hour” (20-25 minutes after sunrise, or before sunset) was the main reason behind the artistic success of the movie.

21. Boogie Nights (1997)

Directed by Paul Thomas Anderson

Cinematography by Robert Elswit

A gripping coming-of-age story of fame and decadence, this movie offered originality and a brilliant ensemble cast when it was released 18 years ago. Most of all, it marked the first big breakthrough for one of the most important cinema voices of our time.

P.T. Anderson used fast camera panning throughout the whole film, in order to capture the instant reactions happening between his actors while having a conversation, and provided a suitable late 70s/early 80s feel to the overall atmosphere. Although most notably, he has a tendency for the long take (which was reminiscent of some classic shots by Ophüls, Welles, Altman and Scorsese), as he created two magnificent ones in “Boogie Nights”; the first one being the glamourous introduction, while the second one coming as a sudden tension-building scene midway through the film.