10. Playtime (1967)

Directed by Jacques Tati

Cinematography by Jean Badal, & Andréas Winding

“Playtime” is the movie that transformed Tati from the “French Chaplin” into a filmmaking phenomenon of the highest esteem, and an artist who changed comedy forever. He envisioned a futuristic metropolitan set, which he built from scratch (aka “Tativille”), and then created a plotless and almost silent comedy/allegory based on his visual orchestration.

Throughout the film, Tati employs geometry contrasts, deep focus photography, architecture, large steel constructions, subtle colors and light reflection, plus some crazy industrial sounds as comedy effects, which altogether succeed in creating a playful visual anthem about the dehumanization of modern man.

9. A Short Film About Killing (1988)

Directed by Krzysztof Kieślowski

Cinematography by Sławomir Idziak

Although a fascinating piece of filmmaking by itself (providing political commentary on society’s class hierarchy, and raising the issue of capital punishment), this expanded version of “The Decalogue, Part V” is better viewed together with the other nine parts of Kieślowski’s acclaimed film series, in order to comprehend the general concept and depth of the director’s tour-de-force.

This particular film relies mostly on image (dialogue is minimal and mainly used as a confessional method) to showcase the true identities of the three main characters of the plot. Idziak’s hand-held camera moves freely all over the place, while his original style of green filtering creates an unforgettable dark and disturbing reality.

8. Aguirre, Wrath Of God (1972)

Directed by Werner Herzog

Cinematography by Thomas Mauch

To this day, this arthouse dramatic adventure (loosely based on real historical figures and events) remains one of the most ambitious films ever made. Despite the low budget, Herzog singlehandedly managed to guide an international cast and crew through the Andes and the Amazon river, and inspired an enthralling performance from his leading man, Klaus Kinski, basically by enraging him continuously throughout the making of the film (there are a number of stories worth reading about their relationship before and during film production, adding to the myth of “the making of Aguirre”).

The film was shot completely on location, taking full advantage of the natural beauty of the virgin landscape, and pushing the boundaries of brave filmmaking to almost unmatched heights. A big part of the shooting took place on rafts constructed by natives, while at times the river was quite unfriendly to the sailing crew; fortunately for us, this is captured onscreen from up-close and distance shots, via Herzog’s constantly moving camera. The first and last shots of the movie tell the whole story about the epic expedition and Aguirre’s state of mind, and they remain iconic and visually mesmerizing.

7. Touch Of Evil (1958)

Directed by Orson Welles

Cinematography by Russell Metty

One of the final film noirs of the genre’s classic era, “Touch Of Evil” was meant to become one of the most talked about films as well, mainly because of the detailed memo Welles wrote to the studio, claiming that the movie was not his version anymore (after the studio’s decision to shoot and edit some of the scenes again at the end of production), and sharing thoughts and suggestions on how to improve the final outcome.

However, the one reason for which this film will always be remembered as a cinematic landmark is the opening long take sequence. Lasting a bit less than 3½ minutes, the camera starts from a close up, continues to a crane shot, and then to an extended tracking shot of great virtuosity. The result was a spectacular continuous one-take, which has been emulated by many great filmmakers ever since.

6. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Directed by Stanley Kubrick

Cinematography by Geoffrey Unsworth

The mothership of all films of the space sci-fi genre, this amazing visual achievement was out of this world when it hit the screens in 1968, and still remains to this day.

The numerous practically “created” special effects (e.g. “zero gravity” – by using wires to hold the actors from the top of the set, and placing the camera underneath their bodies, “artificial gravity” – by placing the camera inside an enormous wheel that caused the entire set to rotate – etc.), paired with fitting classical music, were key contributions to the film’s awe-inspiring atmosphere. Besides that, the movie is renowned for its scientific accuracy, and its ingenious prediction of future technologies (Kubrick proved himself as the equivalent of Jules Verne in filmmaking).

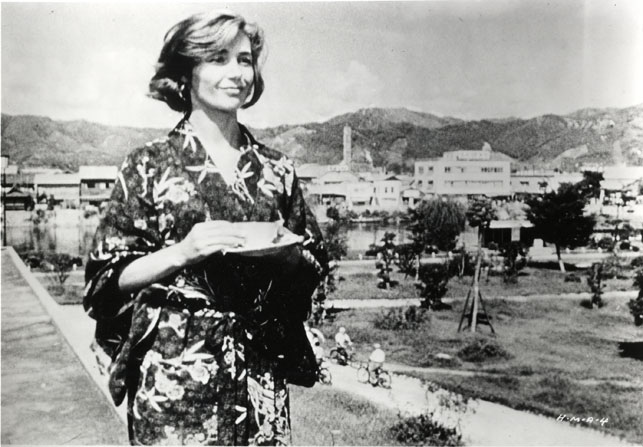

5. Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959)

Directed by Alain Resnais

Cinematography by Michio Takahashi, & Sacha Vierny

A post-World War II poem about human suffering, memory and love, “Hiroshima Mon Amour” is a genuine work of art, and an absolute “Left Bank” cinema highlight.

The movie is a French-Japanese co-production on every level; the shooting locations, the main stars (who fill the screen with their engaging performances), the cinematographers and their crews. Resnais uses a method of circular storytelling, incorporating flashbacks and a slow-paced dialogic narrative style, which matches the idle rhythm of the camera movement in a way that bears a resemblance to his previous documentary work (he had directed the acclaimed Holocaust documentary “Night And Fog” a few years prior to the release of “Hiroshima Mon Amour”), but without recreating it.

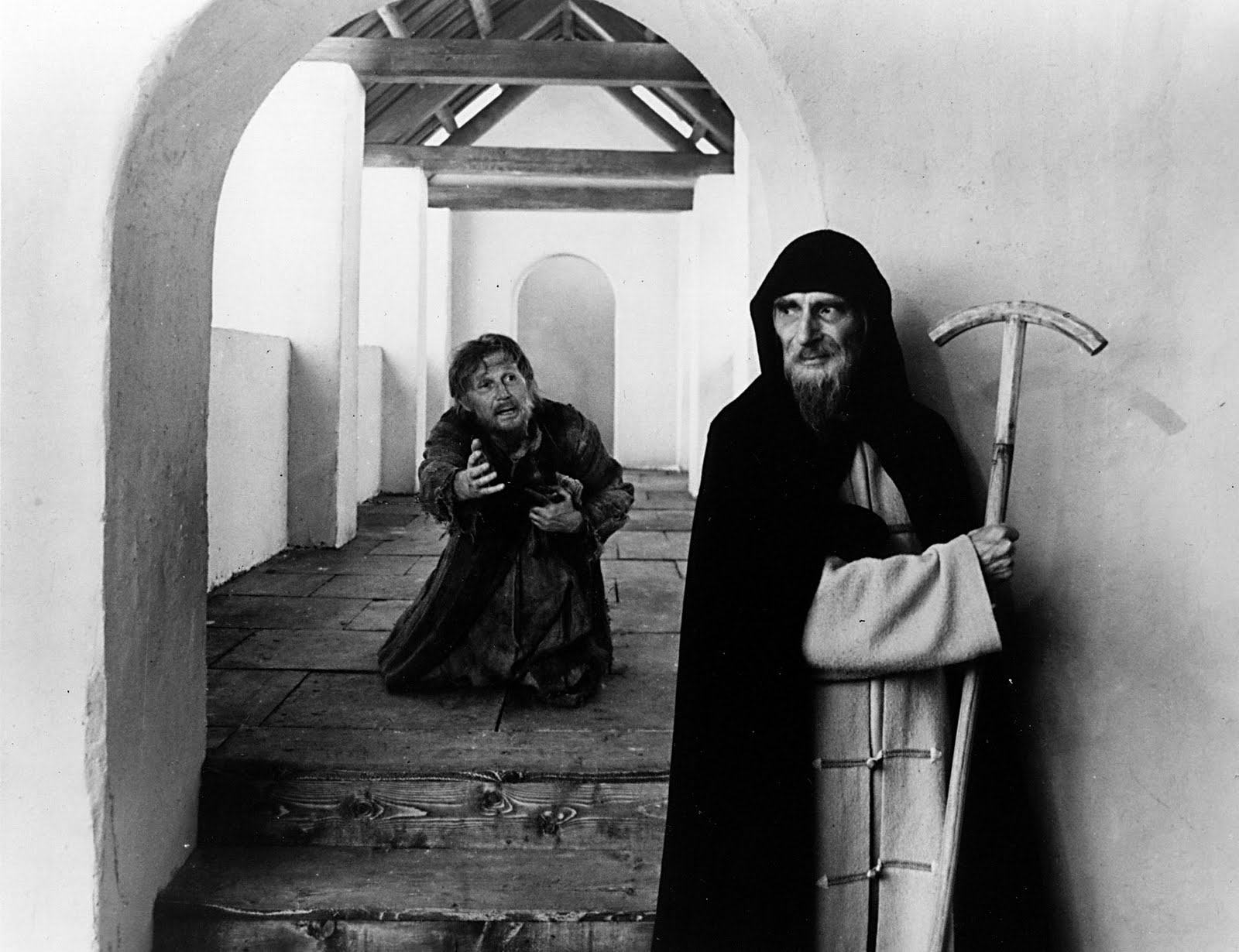

4. Andrei Rublev (1966)

Directed by Andrei Tarkovsky

Cinematography by Vadim Yusov

Andrei Rublev (or Andrey Rublyov) was the greatest Russian icon painter of the 15th century, and a fictional version of his life served as an inspiration for Tarkovsky’s preeminent arthouse film.

The director refused to conform to any storytelling or time constraints, and preferred to concentrate on the painter’s artistic and spiritual journey throughout the riotous Russia of that period instead. Yusov’s black and white cinematography (using wide-angle shots of the large landscapes and the Tatar invasion, among others) serves as an accurate projection of the country’s medieval times. At the same time, Tarkovsky and Konchalovsky’s screenplay succeeds at raising the fundamental issues associated with the human condition, asking from the viewers to do the rest.

3. The Tree Of Life (2011)

Directed by Terrence Malick

Cinematography by Emmanuel Lubezki

Still quite underappreciated due to its enormous ambition, as well as the mainstream audiences’ difficulties to follow its unconventional narrative formula, “The Tree Of Life” has gradually started putting up its reputation as a masterpiece of our time.

The abstract plot centers on a family’s life route, while at the same time pictures related to the creation of the universe and the beginning of life appear on screen (the man responsible for the non-CGI visual effects of this sequence is none other than Douglas Trumbull, who was also the effects supervisor in “2001: A Space Odyssey”), providing metaphysical extensions to the philosophical nature of the film. Regarding the overall aesthetic quality of the cinematography, to say that Lubezki’s use of natural lighting and fluid camera movement is miraculous is an understatement; it is a transcending visual experience.

2. The Conformist (1970)

Directed by Bernardo Bertolucci

Cinematography by Vittorio Storaro

Bertolucci’s triumph is an intense (and probably difficult to relate to) political thriller that focuses on a bureaucrat’s psychological necessity to be “normal” at sociopolitical levels.

In the movie, this meretricious necessity finds its visual analogy in the audaciously gorgeous environments Marcello (the main character, played by Jean-Louis Trintignant) struggles to fit into. Storaro adopts a free-flowing camera rhythm, which in combination with the fascist-era architecture and costumes, monochromes, extreme “Dutch angles” and breathtaking use of natural lighting, creates an immensely seductive reality for a rather problematic individuality. There is a particular low-angle shot of leaves blowing in the wind, which has been imitated several times since.

1. I Am Cuba (1964)

Directed by Mikhail Kalatozov

Cinematography by Sergey Urusevsky

“Soy Cuba” is a Soviet-Cuban co-production, financed by the Soviet Union with the purpose of promoting the ideology of international socialism. Fortunately, the man who took over the job was Mikhail Kalatozov, an accomplished filmmaker who had previously directed “The Cranes Are Flying” in 1957.

Regarding its subject, the movie is an ode to freedom, independence, and the beauty of the wounded – by the Batista dictatorship – Cuba. As the title implies, the film uses first-person narration, which may sound unusual at first, but is indeed an ideal match to Sergey Urusevsky’s virtuoso performance behind the camera. Frame by frame, the whole movie is poetry in motion; the cinematographer takes advantage of every possible and technically impossible shot in the book, as at times we become witnesses of the camera floating, diving underwater, and flying above demonstrators.

Honorable Mentions: “Citizen Kane” (1941), “Rope” (1948), “Ugetsu” (1953), “War And Peace” (d. Sergei Bondarchuk, 1966), “The Godfather: parts I & II” (1972 & 1974), “Stalker” (1979), “Paris, Texas” (1984), “Goodfellas” (1990), “Heat” (1995), “Saving Private Ryan” (1998), “The Return” (2003), “Birdman” (2014)

Author Bio: Andreas Papadakis has been a film lover for all of his life, but it is not until recently that he realized he had a desire for sharing his love with others through writing (hoping that the others will be ok with this). He enjoys a large variety of styles and genres, and he is in the process of creating his own screenplay in the near future, so beware… You can follow or friend him on Facebook.