Comparing works of art is an often self-defeating endeavour, and yet it is inherently compulsive when it comes to film.

Most critics compile a list of the movies which they have most appreciated in ascending order on any given year, and the Academy Awards – arguably the most universally recognised seal of approval for any creative field – are a constant source of controversy, with those shamefully overlooked far more likely to be mentioned in conversation than the times the Oscars actually got it right.

And yet The Godfather, Francis Ford Coppola’s breakout film, occupies a strange space in the public consciousness, a consensus comparable with that of the sacred cows in Hinduism from where the idiom is derived.

It bridges a gap between the snobbish older generation of critics for whom every modern film is a debasement of the art form, and the younger generation of audiences who may have been forced to watch Citizen Kane in class once, but struggled to keep their eyes open. It is, by any standard, a classic.

To say another film is greater, however, is not a damning indictment. It is simply an acknowledgement that The Godfather is not the greatest film ever made. It is not even the greatest crime film ever made. A film which tackles similar themes in an aesthetically comparable way with ever greater success is Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in America.

Leone’s film depicted young, poverty-stricken immigrant life in New York, as well as the rise and fall of criminal enterprise, buttressed by ensemble casting, stirring music and a demanding running length. Yet it is nowhere near as well-regarded as Coppola’s film.

The following are a number of reasons why the disproportionate affection for The Godfather, at the expense of Leone’s Once Upon a Time in America, is a matter which should be rectified, or at the very least debated, by any serious film fan.

1. The Godfather glamorises organised crime. Once Upon a Time in America shows it as it really is.

Arguably the greatest shift forward in progress for American cinema in the second half of the twentieth century was the ending of Motion Picture Production Code, colloquially known as the Hays Code in honour of Will H. Hays, head of the MPAA between 1922 and 1945. The Hays Code had meant audiences were shielded from all but the mildest profanity and violence on screen, with sex practically nonexistent.

It also had meant no crime could go unpunished, and characters who broke the law must be seen to repent before a suitably dramatic penalty, whether it was life behind bars or death in a hail of bullets. The onscreen tracts which bookended pictures like Howard Hawk’s Scarface or William A. Wellman’s The Public Enemy were often laughably didactic (witness the rhetorical “What are YOU going to do about it?” in Scarface).

Chief among the many virtues of The Godfather, according it its devotees, is the non-judgemental attitude it takes towards its central characters. For once, gangsters were not anti-social hoodlums profiteering from a flagrant disregard for laws enacted to protect the common man.

They were sleek, elegantly-dressed family figures who operated according to a code of ethics. They may have lived on lavish estates, and been driven in luxurious vehicles, but their income came from honest, hard-working American capitalism, based on the age-old maxim of supply and demand, whether it be gambling, liquor or prostitution.

Which is all well and good if you want the audience to root for your protagonists, as Coppola and Puzo did. It has little to do with the reality of organised crime. Puzo admitted his sympathies for the Corleones when, reflecting on the success of the film, he attributed his decision to “[make] them out to be good guys, pretty good guys, except that they committed murder every once in a while”.

Roger Ebert said the same when he wrote, in his retrospective review of The Godfather, “Don Vito Corleone [played by Marlon Brando]… emerges as a sympathetic and even admirable character; during the entire film, this lifelong professional criminal does nothing of which we can really disapprove… we see not a single actual civilian victim of organized crime. No women trapped into prostitution. No lives wrecked by gambling. No victims of theft, fraud or protection rackets.”

The same cannot be said for the gang in Once Upon a Time in America. Their plight as enterprising criminals in Prohibition-era America may be compelling, but it doesn’t change the fact that they are extortionists, thieves, murderers and rapists.

The earliest crime we see all four commit on screen is the torching of a newspaper stand, in response to its proprietors refusal to pay local hood Bugsy protection money. As the civilian’s livelihood is incinerated, our ‘heroes’ gasp at the splendour of their handiwork.

This is not the honourable actions of Don Vito and his ilk; this is destructive, greed-driven aggression. And it only gets worse from there.

Later in the story, as adults, Max (played by James Woods), Noodles (played by Robert De Niro) and co viciously beat the staff of a jewellery store in a successful robbery. Noodles goes so far as to sexually assault an employee (one of two women he rapes in the film). Minutes later, they gun down the men who commissioned them for the job, and siphon the profits.

They even swap infants in the maternity ward of a hospital as a means of blackmailing a police chief, and shrug carelessly when the children’s actual identities are lost.

In The Godfather, the only fatalities in the lives of the Corleones are other, decidedly less ‘good’ criminals, such as the Barzinis and Tattaglias. Organised crime is seen as a phenomenon which exists independent of the world around it. In Once Upon a Time in America, we see the consequences of criminality in all its ugliness.

2. The origin of The Godfather is pulp fiction. The origin of Once Upon a Time in America is an autobiographical crime novel.

When Siskel and Ebert gave a glowing ‘two thumbs up’ review of The Godfather upon its 25th anniversary re-release, both were quick to point out how Coppola had improved upon his source material, Mario Puzo’s novel. “This is a greater movie than it is a book”, insisted Siskel. “Well, that goes without saying”, replied Ebert. Indeed, The Godfather is often held up as the quintessential example of how to adapt a wordy bestseller without incurring the wrath of literary purists.

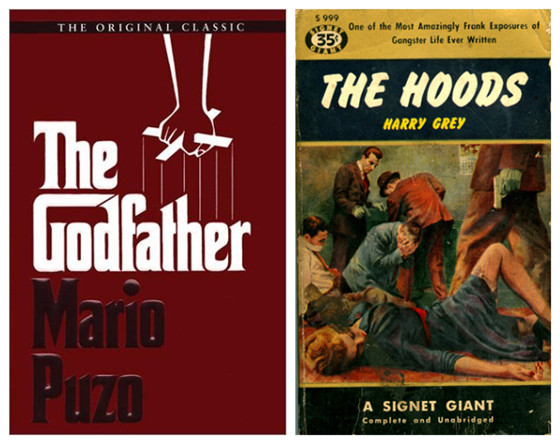

Very few literary purists were ever going to jump down Coppola’s throat, regardless of how the film turned out, for one almost universally-accepted reason: Mario Puzo’s The Godfather is not great literature. A page-turner? Certainly. But a paragon of all that the printed word can achieve? Not in the slightest.

Puzo himself admitted as much many times. His preceding novel, The Fortunate Pilgrim, had not been a success, with his publisher suggesting a greater emphasis on the Mafia would have attracted more readers. Puzo duly got to work, and within six months of its first publication, The Godfather sold 400,000 copies in hardback alone.

Tellingly, the next book Puzo was to publish was The Godfather Papers and Other Confessions, a non-fiction account of the writing of the book and its translation to the screen. Puzo was unapologetically frank; “I have written three novels. The Godfather is not as good as the other two; I wrote it to make money.”

Were Puzo demonstrating an admirable modesty here, it would be one thing. Many great artists have downplayed the strengths of some of their most beloved creations. Bob Dylan once claimed he was “never satisfied” with Blowin’ in the Wind, a “one dimensional” song he wrote “in ten minutes”.

But Puzo’s reservations about The Godfather were shared by the man who would helm the cinematic version. Coppola initially turned down an offer to direct The Godfather after reading fifty pages. “I thought it was a popular, sensational novel, pretty cheap stuff. I got to the part about the singer supposedly modelled on Frank Sinatra and the girl Sonny Corleone apparently liked so much because her vagina was enormous… I said, “My God, what is this…? So I stopped reading it and said, ‘Forget it’”.

Coppola only reconsidered the job offer because of the financial strain of American Zoetrope, the studio he co-founded with George Lucas, and wisely chose to excise the worst passages of Puzo’s text, including the aforementioned subplot about Lucy Mancici’s gynaecological surgery.

The Hoods, the book upon which Once Upon a Time in America is based, was certainly not short of its own sensationalism. “A notorious mob boss of the syndicate tells the full inside story of hired killing and crime operations”, screamed the first edition against a blood-red, gaudily designed cover image. The difference between it and The Godfather was its author’s motivation.

Hershel Goldberg (alias Harry Grey) prepared The Hoods while serving time in Sing Sing prison. It came from a place of authenticity, even if Leone questioned the realism of certain passages in the book, particularly after meeting Goldberg – ‘Noodles himself’ – in New York.

In adapting The Hoods, Leone wanted “to reconstruct the America of Harry Grey exactly as it was, through his eyes. Speakeasies, synagogues, opium dens and everything”.

It was only after meeting Goldberg that Leone realised that he did not conform to the image of mobsters depicted on screen. He was not “Paul Muni in Scarface or James Cagney in The Public Enemy…[he was] a poor man who had tried his luck, a long time ago, with a machine-gun in his hand and a Borsalino on his head: his destiny was to become obscure and miserable”.

Though Puzo no doubt researched the world of organised crime when writing The Godfather, he included errors such as the term “Don Corleone”, a clumsy mistranslation of how the word ‘Don’ is used in Italian (it’s closer to ‘Sir’ or ‘Dame’ in English, meaning “Don Vito” would have been more appropriate). Such missteps were far less likely from an insider like Goldberg.