5. Film Socialisme (Jean-Luc Godard, 2010)

This is not the only socialist film created by the famous French director, and probably is not his best when compared to “Week End” or “La Chinoise”. This film perfectly represents the style and the politics of Jean-Luc Godard in its complexity. Its director was heavily influenced by Marxist ideas and this is a sort of summation.

The film is subdivided into three movements: “Such things”, “Our Europe” and “Our Humanity”. Every chapter represents the deep connection between humans outside of ideological differences or political faiths. The film represents the trial of a new Europe, a crossway of languages and cultures, where society simply overwhelms economics.

Godard is one of the most complicated of directors and his language is very difficult for a spectator who has never seen his films. Derrida and Badiou are the main influences here but Marx could be seen as an “undercurrent” which moves every single idea inside the images.

4. October (Sergei Eisenstein, 1928)

Anyone interested in the way Lenin was able to take control of the Russian political situation during the fateful month of October 1917, should see this film. Sergei Eisenstein, the chief proponent of the Russian montage school creates one of his best works in collaboration with Grigori Aleksandrov.

Spanning from April 1917 when the provisional government took power and Lenin has returned from exile, there’s no clear protagonist in this film since the masses are the true protagonist. Lenin is the only leader who can lead the troubled nation. Kornilov was the general who tried to maintain political calm, but the drastic situation of the proletariat was too bad and revolution was close at hand. The complexity represented by this movie is based on Marxists conceptions.

One of the best scenes renders the representation of religion as “all the same thing” equalizing Christianity, Hinduism, and other ancient faiths. The perspicacious observer will notice the absence of other important personages of the Russian revolution such as Trotsky and Zinoviev. They were cut out of the film.

Lenin is portrayed as the people’s hero and the masses exalt him as the antidote for the bourgeois provisional government. This is a perfect example in understanding the cultural perception of revolution during Stalin era.

3. Man With a Movie Camera (Dziga Vertov, 1929)

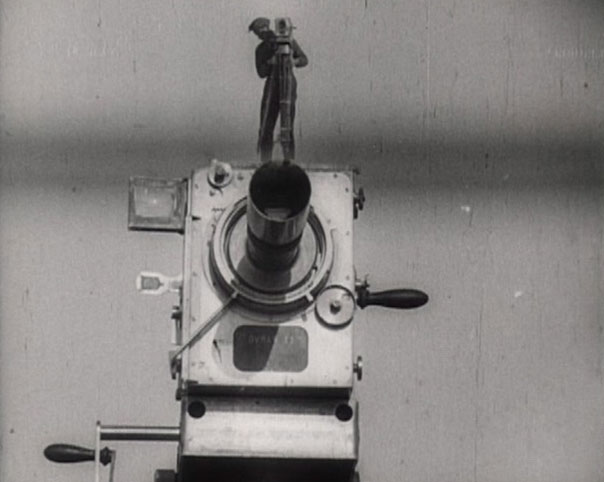

Man with a Movie Camera is one of the most famous works of the Russian montage school and is one of its most experimental movies. It demonstrates a lot of different techniques regarding the positioning of the movie camera apart the obvious montage. With this movie Vertov tried to explain his concept of kinoglaz (movie-eye) through a series of everyday situations.

For the Marxist ideas of film, a director cannot use fictional situations to symbolize reality. The filmmaker has to use images from the real world. Vertov’s purpose was to show the beauty of the industrialized society using only scenes from the society itself. In this movie there are no actors, scenarios, or title cards and the main “protagonist” is the director himself, or better, his movie camera.

The aim is to achieve the perfect overlapping of eye and camera which is reminiscent of the final identification of object and subject in Marxist-Hegelian dialectics. The spectator is faced with a society that is experiencing its continuous evolution thankful to the revolution, socially and technologically speaking.

Communist society is shown at its best while the spectator is compelled to think in a sort of meta-cinema way. Marxists ideas are present here in their purest form. The revolution brought about by the Soviet citizens to their society permits the advent of real technology. Vertov here connects Marxism with the film’s techniques and philosophy.

2. Teorema (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1968)

This film came out during the “hot” year, when students all over Europe were protesting against the institutions. Pasolini depicts a typical Italian bourgeoisie family reacting towards an unknown man.

This film wants to show the reverse alienation of the dominant class, but focuses also on its incapacity towards other humans. When the family meets a mysterious man they are enthralled by his presence. All the true sentiments come from the family only after the man leaves. These range from the religious faith, to love, art and finally the “political” redemption of the father.

Pasolini want to show how the reality of human relationships could be lost if the focus is only on self and superficial and commoditized things. This film is contemporary because humans continue to live in this same situation and refuse to keep open minds as to what truly matters. Marxism in this film reaches its critical point concerning the dominant class existing at a metaphysical level.

1. Battleship Potemkin (Sergei Eisenstein, 1925)

This may be the most famous “Red propaganda” movie of all and there’s a reason for this. It is the story of a mutiny in one of the battleships of the Tsarist Russian naval force. It took place in the Black Sea during the 1905 revolutionary movement. The sailors of the Potemkin rebelled due to lack edible food and seemed destined to be executed for insubordination until one of them, Vakulinchuk, starts a mutiny. The force of the sailors overwhelms officers, doctor and a priest.

The Potemkin arrives in Odessa and the Tsarist troops decide to defeat the rebels. Doing that requires to pass onto civilians. One of the most famous scenes of the history of cinema displays the machine-like advance of the army while women, babies and other people are brutally killed. Battleship Potemkin’s destiny is already ordained but the ship will fall with honor with the red flag of rebellion in the air while the sailors refuse to combat their Tsarist comrades.

It is not an exaggeration to say that this film changed the entire perspective of the word “film” in the cinematic history. Apart the exceptional montage work there’s a clear reference to all the revolutionary movements against the oppression led by bourgeoisie power. The mutiny is towards religion, officers and false beliefs and is the only option possible for the oppressed.

To fall for fighting against oppressors maintains honor and only heroes will be remembered for doing so. In this particular case it would be useful to take a look to the heroic rebels of the 1905 revolution who have risen through time, such as Kalyayev, who became the protagonist of Albert Camus’s play The Just Assassins, or Boris Savinkov.

This film will not explain the Marxist conception of economy but it can explain what could cause a revolution for a social cause. Apart the political beliefs, this film represent an encouragement to fight injustice in any form. In its simplicity it can represents a chant for all the believers in the revolution.

Author Bio: Luca Badaloni is studying his master’s degree in Philosophy. He believes that cinema is a perfect instrument for philosophical ideas and actually society needs critical thinking in several ways. He loves to write script, direct short movies but mostly, he loves reading.