5. Hotel Monterey (Chantal Akerman, 1972)

Chantal Akeman’s 1972 film Hotel Monterey is the second in the series of her New York films. Shot in a residential hotel as an experimental piece, Akerman’s camera invites us into the transient reality of hotel living. Her stationary camera lingers on the lobby, and spends many minutes travelling up and down the art deco elevators.

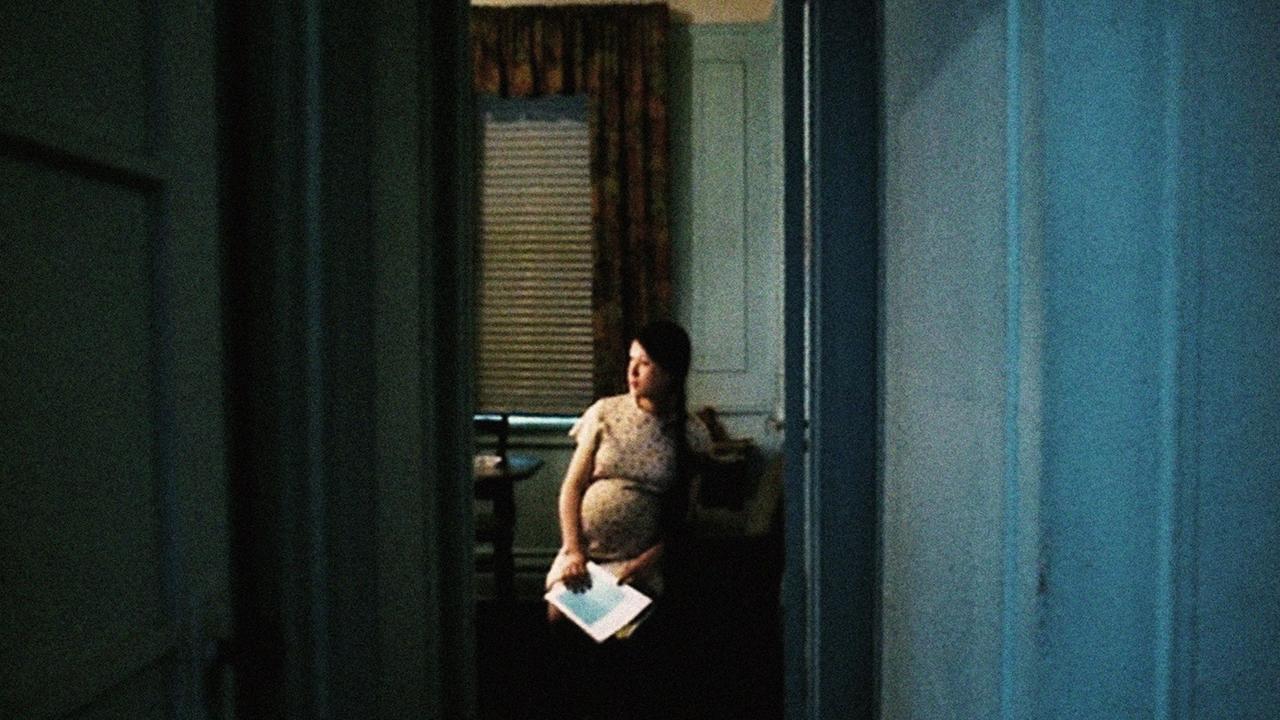

She lingers on fluorescent lights and peeling paint in the hallways. She contemplates empty rooms, beds, and bathrooms. She lets her camera rest on the hotel guests: a pregnant woman and an old man, frozen in position. The muted lighting and static camera give Hotel Monterey the feel of a painting. Her subjects are carefully observed but never interfered with.

Hotels carry a duel meaning. They are places where it is acceptable to be transient and unknowable. At the same time they remain consistent. The same little soaps, the same bed clothes, and the same peeling lobby are eternal and unchanging. This is a place stuck in time, and filled with the memories of all that have come and gone. Hotel Monterey is like a poetic map of this place. The camera moves organically from the lobby upwards, only to end on the rooftop.

This film has no soundtrack. The exclusion of sound enhances the painterly elements and leaves the viewer feeling unsettled. As we look through Akerman’s camera, and gaze upon the garish paint and dirty hallways, it is as though we have always been there.

4. The Red Balloon (Albert Lamorisse, 1956)

A young boy finds a red balloon in the colourless landscape of 1950’s Paris. The balloon and the boy become friends. It follows him from school to church, and back again. In the end they must evade a group of hooligan boys who wish to wreck the balloon.

The Red Balloon is truly one of the most innocent and joyful films ever made. Pascal Lamorisse gives a sweet performance as the guileless little boy, romping about after balloon with a life of its own. Told with incredible love and care this simple story is elevated to the level of fine art. The balloon is an expression of love and friendship. It is sentient but apparently without personal desire. It lives only to help the boy and to be his friend.

Adults have no time for the balloon and won’t allow it inside. Children covet. When they cannot possess it, seek to destroy it. The balloon can be seen as a Christ figure. Taking this embodiment from a man and placing it into an inanimate object creates something special. Balloons are ephemeral and magical by nature. They float above us, only held to earth by a flimsy piece of ribbon. They enchant us as children and we cry if a cruel wind rips one from our hands. They are such true expressions of innocence that we may feel a crippling nostalgia on seeing them.

In the final scene the balloons of Paris rise up in a whirlwind of colour to lift the boy high up into the air. They bring him to a place filled with love and acceptance. In that moment the world lifts and we feel the lightness of childhood once again.

3. The Illusionist (Sylvain Chomet, 2010)

An old time magician finds himself becoming increasingly irrelevant in Sylvain Chomet’s beautiful love letter to faded world. As rock & roll gains popularity, the magician is reduced to performing in ramshackle pubs. Other relics of vaudeville collapse around him. They succumb to alcoholism and oblivion, unable to move with a changing world.

The magician meets a young girl in rural Scotland who follows him back to Edinburgh. At first she seems like a beacon of hope for the magician, though we soon realize her aspirations. She covets the latest fashions and wishes to enter a world the magician never can. In spite of all the heartbreak and sentimentality, The Illusionist is not without comedic charm. The hilarious portrayal of drunken Scotsman, unaware of their dangerously flapping kilts and unintelligible dialect, lend the biggest laughs in the film.

The Illusionist contains very few words. Most everything is expressed through though the visual acuity of the animation. Unlike the grotesque characters of Chomet’s 2003 film The Triplets of Bellville, the main characters of The Illusionist are painted more realistically.

The grotesque and profane are reserved for characters outside the lonesome magicians reality. They are absurd representations of something the magician won’t understand. He must fade away and surrender himself to obsolescence. He boards a train and leaves for a destination unknown. All we know or understand is that he has gone away forever.

2. Window Water Baby Moving (Stan Brakhage, 1962)

In 1962 Stan Brakhage filmed his wife, Jane, giving birth to their first child. The resultant film is perhaps one of cinema’s purest testimonies to the power of love. Brakhage’s jumpy editing and beautiful use of montage come together to create a visual experience that is more song than film.

Water Window Baby Moving is shot almost entirely in close up. Brakhage draws us into this singular world and we see Jane through his eyes. Through all the pain of childbirth she remains radiant and desired by a camera that caresses every shadow on her face and the endless curve of her belly.

As the film progresses and birth becomes imminent, the imagery turns graphic. Even then, when blood s from Jane’s vagina and the child is yanked from the womb, we cannot look away. Brakhage understands different kinds of beauty; he understands that there is nothing disgusting about what happens to Jane’s body. It is all necessary to the wild love projected all over the screen. In the seconds after the child is born, Brakhage turns the camera on himself and the look upon his face is one of such joy that it cuts through any apprehensions.

Brakhage rarely used sound in his films. He embraced the aesthetic of ‘pure’ cinema and thought that use of sound only impeded his visual language. This film is a rhythmic expression of this idea, but it is pure in other ways.

Though Brakhage uses montage to connect windows to the birth, and shimmering water to convey the primordial undercurrent of Jane’s labour, the film lacks pretention. These metaphors are so gentle that they don’t leave one intellectualizing what is on screen. Water Window Baby Moving is simply a virtuosic expression of deep love, exploding and embracing the viewer.

1. La Jetee (Chris Marker, 1962)

Chris Marker’s La Jetee (1962) is a strange odyssey through time. A man is haunted by the memory of a woman in the seconds before the outbreak of World War III. As citizens swarm under the ground to evade a radiated earth, a new society forms of victors, and prisoners. The victors, realizing that their only salvation lies in time travel, perform experiments on the prisoners. Their subjects suffer from death and madness. Only the man obsessed by a memory is able to make the journey.

Marker’s use of still photography creates a deeply poetic viewing experience. La Jetee is a monument to the moments between movements. Like the memory threaded through the narrative, the viewer is moved by the anticipation of gesture. Marker has made a film in which the prosaic becomes profound. Instants of emotional contemplation are given weight beyond their apparent meaning. Ordinary moments are indistinguishable from memory until events give them worth.

La Jetee is narrated but there is no dialogue spoken by those on screen. Without dialogue the film takes on the feel of a diary entry. There are moments that feel too intimate to be seen. As the man and woman explore an exhibit of taxidermy birds, they are witnessing a thousand frozen moments. The birds surround them and their time together is joyful. La Jetee is a film about the meaning we give to ourselves.

Author Bio: Lex Corbett (@trazism) is a freelance writer and filmmaker based in Toronto, Ontario. She has studied cinema, both theoretical and practical, at the University of Toronto and OCAD U, respectively. Along with Taste of Cinema, she also writes for Vague Visages.