6. Frida (2002)

Having obtained her bachelor’s degree in folklore and mythology, it should come as no surprise that Julie Taymor would direct Titus (1999), The Tempest (2010) and A Midsummer Night’s Dream (2014). Yet, her greatest cinematic success came with Frida in 2002 (though she has had almost equal success in the theatre). Frida received six Oscar nominations, and two Oscars, for make-up and for the music score by her husband Elliot Goldenthal.

Frida relays the professional and private life of the surrealist Mexican painter and feminist icon, Frida Kahlo. Salma Hayak does an admirable job as the fickle Frida and the incomparable Alfred Molina stars as her brilliant, yet restless, husband, Diego Rivera. The movie was adapted by Clancy Sigal, Diane Lake, Gregory Nava and Anna Thomas from the book Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo by Hayden Herrera (herself an art historian and who has curated several exhibitions of art).

Curiously, Salma Hayak was given the role of Frida only after Laura San Giacomo, Madonna and Jennifer Lopez were selected, then dropped, because of what was perceived as their apparent lack of “Mexicanness”. But, then, given the historic importance of Kahlo, it was important to have her role portrayed as accurately as possible. Diego Rivera, of course, was the famous Mexican muralist and self-described communist, who partied with the wealthy while marching with the workers in the streets of Mexico City.

But Kahlo was no simple Mexican wife who occasionally painted. She expressed her Mexican pride and sexuality with a ferocity that would not become accepted for decades. As for her painting, it was brilliant and brutally honest. Throughout the film, a scene starts as a painting, then slowly dissolves into a live-action scene with actors.

In the film, Taymor avoids the typical martyr/victim theme often typical of biopics about artists, and instead focuses on the development of Kahlo’s strong personality, her role as a painter and the love Kahlo shared with Rivera (and others). Taymor also captures both the glamorous, deeply cosmopolitan milieu Kahlo and Rivera inhabited, and the importance Mexico had in the 1930s for the international left.

Documented well is the tempestuous relationship Kahlo had with Rivera, what with Rivera’s compulsive infidelities (including an affair with Kahlo’s own sister); the couple’s erratic, extremist politics; and, eventually, Frida’s own amorous adventures with men and women – including Leon Trotsky and Josephine Baker.

The strength of the film survives the clearly inauthentic role played by Geoffrey Rush as Trotsky. Kahlo is a woman well ahead of her time, and the fact that she was a female Mexican artist married to a famous womanizing artist makes her story all the more compelling, and the film that important to see.

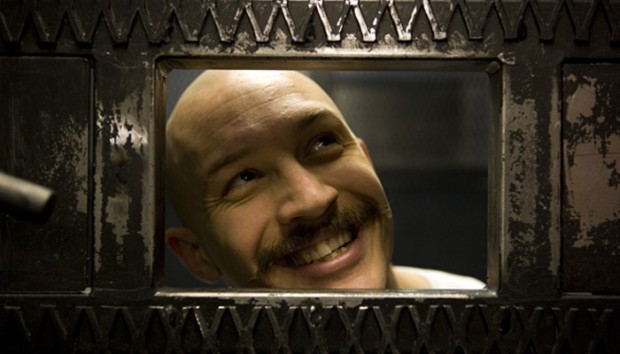

7. Bronson (2008)

If there is no other reason to see this most British of films, one must see it for Tom Hardy’s portrayal of the mad man often referred to as Britain’s most notoriously dangerous criminal. While often known for his action roles (Star Trek: Nemesis; Black Hawk Down), Hardy is a versatile actor, having played a variety of roles (Child 44, The Drop).

Knowing that Hardy spent his teens and early twenties battling delinquency, alcoholism and drug addiction, one gets the frightening impression Hardy is most “at home” in Bronson.

Bronson is a fictionalized account of the life of the career criminal, Michael Gordon Peterson, born by that name in 1952, but later changing his name several times. In 1974, Peterson decided he wanted to make a name for himself and so, with a sawed-off shotgun, he attempted to rob a post office.

Swiftly apprehended and originally sentenced to seven years in jail, Peterson would spend the next thirty-four years behind bars, thirty of which were spent in solitary confinement. During that time, Michael Petersen, the boy, faded away and “Charles Bronson”, his superstar alter ego, took center stage.

Narrated eerily throughout by Bronson/Hardy with humor, the film often blurs the line between comedy and horror. The film is a story of man against society, but Nicolas Winding Refn, the Danish director most famous for his Pusher trilogy of films about macho posturing in Copenhagen’s violent, multi-ethnic underworld and himself something of a rebel, makes sure to point out that Peterson’s rough childhood was largely self-inflicted, i.e., not the product of a broken home, drugs or alcohol.

Indeed, the movie begins with Bronson’s childhood (beating up class bullies, assaulting a teacher in a classroom), continues through his endless bloody encounters with prison staff, all brought on by himself, a period of heavy sedation in a mental institution (reminiscent of A Clockwork Orange), a stint at large as a bare-knuckle boxer and a final, defiant demonstration of recalcitrance in the prison art studio. Putting the film’s subject in stark relief is the film’s many still and off-center shots, typical of European cinematography.

Of course one could say that some people are simply born evil. “Society”, as it were, had little to do with Bronson’s recidivism. He was always far happier in a claustrophobic world of prison bars, crashing doors, cages and straitjackets than enjoying the supposed lack of restrictions in normal civilized life.

In the end, Bronson isn’t a story in the traditional sense at all. It’s a meditation on the art of rage – an action painting passing itself off as an action movie.

8. The End of the Tour (2015)

In a 1996 interview with Michael Silverblatt, David Foster Wallace stated his magnum opus, Infinite Jest, was structured like a Sierpinski Gasket. A Sierpinski Gasket, incidentally, is constructed by taking a triangle, removing a triangle-shaped piece out of the middle, then doing the same for the remaining triangles, potentially ad infinitum.

To say David Foster Wallace’s writing is “difficult” is really to say that it does not conform to the common literary paradigm of linearity. One only need refer to the writing of Thomas Pynchon and Don DeLillo as additional examples.

The End of the Tour recounts the five days that Rolling Stone columnist David Lipsky accompanied and interviewed Wallace during his book tour promoting Infinite Jest. Directed and written by James Ponsoldt, this recounting is based on Lipsky’s best-selling memoir, Although of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself.

Interestingly, many of Wallace’s well-known were originally written as commissions from various periodicals (see, e.g., the collection of Wallace’s in A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again, which, incidentally, provides an excellent introduction to Wallace’s oeuvre, in terms of how he writes, and what makes him tick). The film is actually not the first film about Wallace, with John Krasinski having directed in 2009 an adaptation of Brief Interviews with Hideous Men, a collection of short stories by the same name written by Wallace in 1999.

Tasked with the monumental task of portraying the immortal Wallace is Jason Segel, a perhaps counterintuitive choice, but one that paid off handsomely. Equally wise was the casting of Jesse Eisenberg as Wallace’s interviewer, David Lipsky. Both labored mightily in preparing for their respective roles, and it showed. Of course, the greatest appreciation for the film comes from having read Wallace’s intellectual doorstop of a novel, Infinite Jest, as well as others of his works.

The film also deftly captures the curious artificial intimacy that can arise in the process of interviewing, at length, the subject of a magazine profile, and the moments of betrayal that can result, such as when Lipsky takes advantage of Wallace’s “captivity” on a flight to ask him about Wallace’s brief stay in a mental institution, understandably not a welcome subject to Wallace, and the source of a testy exchange between the two.

Despite the overwhelmingly positive critical response to the film, Wallace’s estate has disavowed it, his wife lamenting that Wallace would never have approved of the film. Anyone who has watched his interviews would probably attribute any such possible reaction by Wallace to Wallace’s humble, self-effacing nature – at times almost appearing desperate in seeking approval from those who are but gnats in the presence of such an intellectual giant.

It is no wonder that the New York Times has referred to Wallace as one of his generation’s pre-eminent talents. It is a bitter tragedy that his death has left us suffocating for his brilliant, witty, and wonderfully meandering observations.

9. The Magdalene Sisters (2002)

This film, concerning a subject that assaults one’s sense of justice, tells the story of three young women whom, under tragic circumstances see themselves cast away to a Magdalene Asylum for young women in 1964.

To understand the significance of this story is to understand the influence of the Catholic Church in Ireland, even during this time. While diminished somewhat in recent decades, the Catholic Church has had a powerful influence over Irish society throughout history.

This pall of this influence would only be put in starker relief during the period of time known as “the Troubles”, the common name for the ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland that spilled over at various times into parts of the Republic of Ireland, England and mainland Europe.

These medieval and cruel institutions were known in Ireland as the Magdalene Laundries, referring to the work the jailed victims were doing, and so named after Mary Magdalene, who was wrongly thought to be a prostitute. Several such places existed in Australia, England, Ireland and even in North America. They were created to house those women who had “fallen from grace”, i.e., those that the extremely conservative Church and Catholic laity considered scandalous.

Guarded by nuns, the women were subject to forced unpaid labor for the benefit of the Catholic Church. Though they did not initiate the facilities, most of the operations were carried out by the Sisters of Charity, the Sisters of Mercy, Good Shepherd Sisters, and the Sisters of Our Lady of Charity, with the full support of the Church.

Locked away with no identities, no visits, no human rights, the women were treated as criminals without any trials and no judgments. They had to scrub prison floors, cook for the nuns, take care of aging prisoners and other tasks nobody wanted to do. They all lost their children to adoptive families chosen by the nuns. It is estimated that 30,000 women were detained in these asylums in Ireland alone. The last one was not closed until 1998.

The film was written directed by Peter Mullan, a committed social activist, and an actor best known for his acting roles in Trainspotting, the Harry Potter film series, My Name Is Joe and Braveheart. He was inspired to create the film after having watched Steve Humphries’ Sex in a Cold Climate, a documentary denouncing the Magdalene Asylums.

The roles are well cast, with Geraldine McEwan deftly portraying the “Nurse Ratched” cruelty of the head Nun, Sister Bridget.

The Catholic Church amazingly still denies that these abuses took place and has steadfastly refused to apologize for what it says never happened, even after Ireland’s Prime Minister Enda Kenny issued a full state apology to the victims in 2013.

10. Milk (2008)

This moving biopic about the slain gay-rights activist Harvey Milk is not only the story of a political leader but a political event in its own right, introducing mainstream moviegoers to a martyred hero and implicitly championing his ideals.

Known in San Francisco as the Mayor of Castro Street, Milk pulled off an impressive balancing act in the mid-70s: though he worked tirelessly for gay rights, he also assembled an unlikely power base of gays, hippies, seniors, union members, and small-business owners that catapulted him to elective office on the city’s board of supervisors.

Harvey Milk was a 40-something gay Republican when he moved to San Francisco in the early ’70s. He opened a camera shop on Castro Street. He quickly determined to bring what was then a distressed neighborhood back to life; to make it a “gay Mecca.” Director Gus Van Sant shows us that transformation in quick strokes — business owners who journey from hatred to profit, unions earning gay help to win contracts — with police harassment and murderous gay-bashing as a backdrop.

Perhaps the defining political fight of Milk’s career was his successful battle against Proposition 6, a statewide measure that would have banned gays from teaching in California public schools. Milk saw this not as an economic issue but a cultural one, a reason for gays to come out of the closet and tell everyone who they are.

It is impossible to see the film’s anti-Prop. 6 demonstrations, to read signs saying things like “Gay rights now” and “Save our human rights,” without thinking of the battle over Proposition 8 and its ban of gay marriage that was raging in California at the time. This graphic demonstration that the struggles are far from over gives “Milk” a harder edge than its otherwise self-congratulatory tone could manage.

“Milk” owes a large debt (which it acknowledges in the closing credits) to the 1984 Oscar-winning documentary “The Times of Harvey Milk.” It goes so far as opening in the same way, with a scene of Milk recording his taped final testament, to be played “only in the event of my death by assassination”.