11. Traffic

Simultaneously one of Steven Soderbergh’s most radical films and one of his most docile, Traffic is cinema as human carnival, as existential quandary, as cluttered moment-to-moment last-breathing, and as cinematic experiment. The elegantly interwoven tale of drug dealers, drug users, drug enforcers, and drug haters is suitably messy and confrontational, reminding us that no matter who we are, we are all drug somethings, and certainly not drug bystanders.

Watching Traffic is a study in cinematic contrasts. The most obvious for many viewers will be in the performative realm, with the vivacious vixen-like veracity of Catherine Zeta-Jones almost violently cutting into the weary, cracked incapability and masculine brutishness of a self-critical Michael Douglas.

Elsewhere, the everyday domesticity of Don Cheadle evokes the businesslike tenacity of the dogged trudge of the everyday grind, and Benicio del Toro turns his aged face into a craggy desolation. Life around drugs has turned all of these individuals into simultaneously passionless and impassioned figures, and the odd-angles at which they intersect forms the backbone of a tale where victory is but another self-administered deceit to survive another day.

The boldest cinema of Traffic, however, is the gamut-running cinematography (also by Soderbergh, as is his custom, under a pseudonym). The serrated edges and sharp detachment between each of the stories – and between characters who either do not know one another or who do not care – are categorized visually in the film’s palette.

The film splits its time difference between Mexico – suffused in a gaunt, malarial yellow of gallows grit – suburban middle American – clipped to lifelessness with a digitally chilly and antiseptic blue to critique the judicious, hammer-of-God anti-drug judge who spares no humanity for anyone but himself – and a haughty San Diego – over-lit and given to harsh, artificial contrast to explore the artificial SoCal lifestyle.

The end result is a work where each story threatens to stab into each other with harsh visual contrast, and the sheer lack of communication between these characters, the isolation of their individual worlds and how situationally incapable of considering one another they are, bleeds into the isolation of the celluloid segments themselves.

Traffic is not a perfect film. The length and the somewhat sour-pussed dourness would drown out the cinematic life of a multitude of “connect-the-dots” films to follow throughout the 2000s, and the sheer cinematic fury of the cinematography and performance doesn’t fully erase the occasional narrative still-water here either.

Plus, Traffic is still Oscarbait, and the ensuing stateliness of the production stunts it from the sort of fallout a truly radical film might boast. Still, if every Winter must carry with it a case of the Oscarbait sniffles, the symptoms are far more enlightening when the virus strand is Steven Soderbergh.

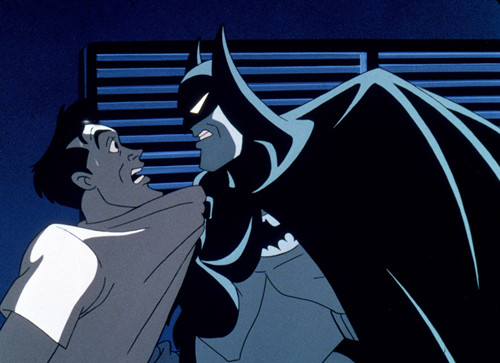

12. Batman: Mask of the Phantasm

With all apologies to the deliciously idiosyncratic pop-fantasia and satire of suburban sitcom culture in 1966’s Batman film (fronted by the indomitably straight-jawed Adam West), Batman: Mask of the Phantasm remains the best Batman film to be directly adapted from a specific television show. Partially, this is simply a question of raw architectural girders; the strengths of Mask of the Phantasm in part merely reflect the strengths of 1992’s Batman: The Animated Series upon which the film is based.

The show, with its Art Deco influenced noirish artwork and nightmarish city-out-of-time sense of chaos, unearthed the intersection between entropic absurdist children’s television programming and the post-Weimar expressionism that birthed American pulp fiction and Batman altogether. The film is more of the same. But if it ain’t broke…

Admittedly, the film does expand on the pop-morality of the television show with a desperately dour, dejected, bifurcated narrative about a killer masquerading as Batman and a woman whose internal trauma mimics Bruce Wayne’s. The sense of consequence is mortal, the lingering sewage of a deconstructed geometric urban hellscape is nearly murderous in its impact.

Mask of the Phantasm posits an alternative cavern for Wayne to have fallen into – a cavern of mourning turned into fear, and fear curdled into abuse and dictatorial justice – and it has the dark heart to question whether this “alternative” really isn’t the conventional story we already know.

13. Pennies From Heaven

Say what you will about Pennies From Heaven, but it asks for the disgrace and the disagreement. The anti-musical has been so long misunderstood by the general public in large part due to its deceptively misbegotten nature. Condensing the television miniseries of the same name about a despicable, misogynist salesman and the forlorn, tortured, cutthroat Great Depression popular culture he represents, Herbert Ross’ film version sacrifices none of the perplexing self-contradiction and deliberate triviality of the original show.

Where do we begin? Steve Martin, at the height of his hot-button commercial pop culture icon du jour moment in history, ing a predatory, barbarically lecherous man who stands in for a cruel and sexually depraved culture?

A nasty-minded screenplay that shrewdly dissects a cynical “cold winter of death” time in American history, while said screenplay is also intercut with fits and spasms of dementedly lustrous pop numbers that fly as high as the sky whilst also uncomfortably contrasting the social anomie and malaise of the narrative? The bipolar manic-depressive temper of a perversely mercurial film visually and aurally quotes primary-colored, soft-hued icons of ’30s pop culture while flaunting their inability to address the central narratives themes.

Primarily then, we have a film of boisterous, frenzied, hyper-zealous musical numbers grazed on presentational wonder that also indict its very musical numbers at nearly every moment, up to and including the introduction of musical numbers that, in tone and lyrical conceit, directly contradict the disillusioned spirit of the scenes that proceed them.

As difficult as the film is already, Pennies the anti-musical is the easy part. The true challenge is to peer through the diabolical self-criticism of the film and entertain the mournful ode to humans dreaming and applying the false pretenses of pop culture as their own unconscious collective dream.

The energy with which the film stages its elaborate musical numbers is not mere skepticism, but a perverted radical love wherein artificial pop culture that we know to be artificial and arbitrary nonetheless bides the time, and allows the mind a temporary escape, when the body has nowhere to go. By all means, Pennies From Heaven is adamantly a lament for a rotting culture that requires the musical to begin with, but it is also a paean to the musical as a form of self-expression, even if the expression is a lie.

14. Head

Many cinematic acid casualties lie entombed amidst the twisty, foggy, possibly toxic nether of the late ’60s. Head, a quasi-adaptation of The Monkees, has largely gone the same way as the band upon which it was based: quietly, without fanfare, to the land of the lost pop culture references. Which is a shame on both fronts; The Monkees, the band, were a talented band of wishful, wistful avant-garde adolescents who were beset by corporate producers curtailing their more endearingly bizarre interests, but their television show saw them unleashed.

It remains one of the great applications of absurdist cartoon logic to the live action realm, and thus all the more disobedient and recklessly fascinating for how nominally of our world it exists whilst thoroughly rejecting and almost fanatically breaking with the rules of our world.

Fittingly, Head has the same adolescent issues as the Monkees themselves: unresolved angst at being lesser than a partner forebearer, The Beatles in the case of the band and The Beatles’ A Hard Day’s Night, in the case of the film.

Head is never as diabolically juvenile and as fascinatingly quizzical as A Hard Day’s Night, a work with an almost infinite untapped well of questions about “The Beatles” as enigmas, public identities, corporate constructs, childlike ids, and unknowable regions of the popular consciousness. Nor does Head quite match the bedazzled cinéma vérité meets psychedelic dream anti-logic of A Hard Day’s Night.

But then “not being one of the greatest British films of all time” is not exactly a fair criticism, and Head is a gilded treat in its own right. A fever swamp of full-throated concussive mania wrapped around a freely flowing spectral haze, Head is no less a mercurial amalgamation of leaping abstractions and cheeky hidden hostility than The Beatles’ cinematic masterpiece from a few years prior. The band begin the film with an ode to artifice, a reminder that they deconstruct their own manufactured nature by embracing it and turning their image – and the manufactured decade they inhabited – into their toybox.

Much like the decade, the film finds stuttering pop-psychedelia and entropic conflict trapped in a trance by the prismatic beam of artistic insanity as the band tackle nearly every film genre in cinema history and bend them to their liking. Head remains one of the most adamantly inexplicable acid casualties of a lost decade that began in earnest by getting pyschoed and ended up a flying circus. Perhaps it wants to be hidden. That way, it can be rediscovered.

15. Monty Python and the Holy Grail

Writing about one of the most loved comedies of all time is a Sisyphean task, if a pleasurable one. Of the three Monty Python feature films, the third best captures the shambolic stream-of-consciousness flavor of the televised production, the second is the most intellectually cohesive. But the first film, and justifiably the most famous, remains their crowning cinematic achievement.

Unlike Meaning of Life, it doesn’t reduce itself to the level of televised also-ran sketches, but it does not adhere too ascetically to the conformist rules of claustrophobic narrative cinema like Life of Brian; The Holy Grail hits the precarious sweet spot of contorted cohesiveness, of untethered symmetry, of raging, prismatic centeredness.

If the second Monty Python feature was so streamlined that it could be accused of relative sanity, and the third too pointlessly insane that it barely registered as an attempt at a film, The Holy Grail singularly lies in the uncontrollable realm of hazardous narrative uneasily matched to insecure episodicness.

It is not the mind regained (Life of Brian), nor the mind already lost (Meaning), but the mind in freefall, struggling to put the pieces together and not yet willing to admit that its uncontainable tangents would soon have the better of it. The Holy Grail is engorged with timelessly quotable moments, but it is the fact that it so desperately pretends to link them whilst wholly laughing in the face of its own cohesion that marks it as the Python’s most entropic experiment in the limits of narrative cinema.

What is often left undiscussed in the universal outsider love-fest directed The Holy Grail’s way is the ramshackle visual anti-panache Terry Jones brings to the production, deliberately recreating not the Middle Ages as they existed in reality but as a dilapidated, neglected, stage-bound version of the time period – more the version as it existed in fictional memory than anything else.

As much as The Holy Grail revels in outright absurdism and perverting the legitimate Middle Ages, it takes no less delight in wrapping its carnival glove around the way time and pop culture have diluted the Middle Ages into a kitschier beast altogether, the sort of location where corroded empty spaces strangled themselves around the fingers of gilded castles built on improbable badlands where magic was a deus ex machina to solve any and all social woes.

The drug-induced, barely cobbled-together B-movies of the 1970s are a particular target for the Pythons’ withering put-downs, with the slapdash world of The Holy Grail a satire of the equally sickly, slapdash worlds of so many other artificial fantasies that straight-faced films produced in the 1970s.

Monty Python and the Holy Grail is not only an ingenious comedy vis-a-vis clown school history, but a salient, learned rib-tickling chopping block upon which cinematic history – and especially matinee cinematic history – must lay its frail, withered neck.

Author Bio: Jake Walters is a recent graduate of Amherst College and an aspiring film-writer/ist. He shares his thoughts on film at his website, thelongtake.net and is particularly interested in film in relation to society, race, class, and gender, He writes frequently on horror films and looks to Werner Herzog, Michel Foucault, and John Shaft for life advice. You can find him on Twitter@long_take.