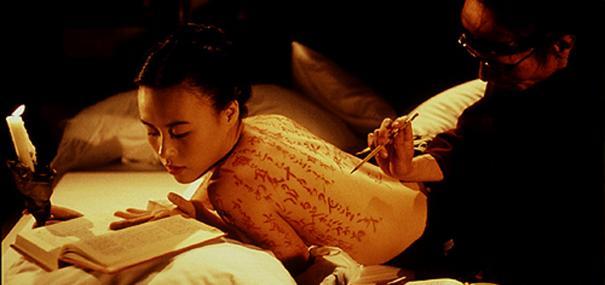

7. The Pillow Book (Peter Greenaway, 1996)

Art-damaged to the nth, chiarusco figures predominantly in Peter Greenaway’s adventurous and skewed riff on the Japanese classic, agin lensed by longtime collaborator, the late and legendary Sacha Vierny.

Vierny first came to fame working with Alain Resnais on classics like ‘Hiroshima, Mon Amour’ and ‘Last Year at Marienbad’ and Luis Buñuel on ‘Belle du Jour’, but his work with with Greenaway was anything but traditional. Featuring a number of novel visual devices (picture-in-picture, projected images of calligraphy), Vierny assists Greenaway in a deconstruction of cinema as audacious as his work on ‘Last Year at Marienbad’.

Professed to be a story of Nagiko and her search for the perfect writer/calligraphist substitute for her father (‘Mishima: a Life in Four Chapters’ Ken Ogata), the film is a textbook example of the sort of visual experimentation and style Greenaway is known for: a multitude of nudes parade throughout, the sensual lighting of flesh and its spectrum of skin tones provoking an instinctual reaction from the audience, much like a Rembrandt painting, whether it be in the unforgiving glare of electric light, the seductive glow of candlelight, or light reflected on moving water.

Stripped of any prurient value by the director’s dispassionate attitude toward nudity (another of the director’s trademarks), the ample flesh displayed in such a variety of manners becomes an intellectual appreciation of the human form. Our biological predilection towards that small brownish slice of the color spectrum is given free reign as Greenaway conducts visual experiment after experiment (although perhaps not quite redefining the way stories are told cinematically per his audacious claim).

Another in a long series of complex and layered meta- metaphorical films, ‘The Pillow Book’ is something like a porn flick directed by a 17th century master.

8. Fa Yeung Nin Wa (aka In the Mood for Love) (Wong Kar-wai, 2000)

No list like this would be complete without discussing the films of Wong Kar-wai and this, his fifth collaboration with cinematographer, Christopher Doyle (Jim Jarmusch’s ‘The Limits of Control’ being one of his infrequent collaborations with other auteurs). ‘In the Mood for Love’ is the gentle and lyrical story of two neighbors (Tony Chiu Wai Leung and Maggie Cheung), both of whom suspect their spouses of infidelity, and the strong, platonic friendship that develops between them.

Through the use of colored filters and complex lighting arrangements, Doyle separates these two characters from their backgrounds, emphasizing both their beauty and loneliness. Sparse on dialogue or any traditional form of action, the film relies on the space between words and the lighting to express itself, set design and costuming taking on enhanced roles as well.

Originally planned as a more traditional love story, replete with more dialogue and scenes of lovemaking, director Wong (who traditionally shoots without a script) decided on a more low-key and subtle form of tale telling. Much of the success of this approach is predicated upon the skills of the cinematographer and quality of the lighting, two artists who have taken a simple romance set at the end of the 1960s and transformed it into a dreamlike vision of times past.

9. The Isle (aka Seom) (Kim Ki-duk, 2000)

Self-trained as a painter after moving to Paris, Kim Ki-duk is a director whose films polarize audiences, especially in his native country of South Korea, and leave even his most ardent supporters with mixed feelings.

The first thing critics noticed about this film (after the disturbing violence) was the artistic use of light. For a film that reportedly only cost $50,000 to make, it stands head and shoulders over many others that spent ten times that much and owes much of its greatness to the cinematography and lighting of Seo-shik Hwang.

Utilizing the lake upon which this tale takes place to good advantage, we see it dressed in a variety of lighting schemes: harsh, direct sunlight, nighttime light by lanterns, soft greyish light diffused by mist, and the blue-green glow of sunlight underwater.

As most of the film is dialogue-free, the visuals take on an expanded role in delineating the plot, a metaphorical tale of the eternal battle of the sexes on water that tells how a mute prostitute with a mean streak in charge of renting houseboats to businessmen for the weekend meets a suicidal cop on the run, and how they find redemption in each other after some nasty business with fish hooks.

10. Janghwa, Hongryeon (aka A Tale of Two Sisters) (Jee-woon Kim, 2003)

One of the creepiest films to date, Asian or otherwise, Jee-won Kim conjures up a constant and unrelenting atmosphere of dread, much of which is achieved through his use of lighting. The film opens with sunny, exterior shots, and there is a an interlude that takes palce outside by a birdcage, but the bulk of the running time is devoted to spooky interior shots. Even those shots that happen in the daytime are filled with shadows and that sense of dread.

In addition, one of the only brightly lit scenes is also one of the most chilling (the dinner scene and the apparition under the sink). From this, surprisingly his first film as cinematographer, Moe Gae-lee has gone on to lens equally strong Korean offerings like ‘Ang-ma-reul Bo-at-da’ (aka ‘I Saw the Devil’) and ‘Joheunnom Nabbeunnom Isanghannom’ (aka ‘The Good, the Bad and the Weird’) for director Kim.

‘A Tale of Two Sisters’ has been accurately described as “Korean Gothic” as well as a loose adaptation of the Korean fairytale it derives its name from. One of the tropes of that genre is the Gothic house, full of mystery, unexplainable events, and the revelation of dark secrets, all reflections or projections of the characters mental disturbances and past transgressions.

To maximize the identification of the house with the psyche of the the cast of characters (two sisters, their father, and his wife, their traditional evil stepmother), and in an attempt to create “a sense of color that wasn’t there in Korean horror films before’ Kim shot each of their rooms through a colored cloth: purple for the stepmother’s room and green for the sisters’ rooms. As is common to many horror films, red is a signature shade, here represented by flowers, the sisters clothing, various scenes involving blood, and the tense family dinner scene.

As described by one reviewer, the house itself seems veined with blood. The film offers no break from the tension, with even the brightest colors carrying a dark meaning: many times the brighter the color (for instance, the kitchen floor), the greater the psychic disturbance exhibited by one or more characters. The darkness that permeates the house gets inside the viewer and follows them after the film has ended.

11. Constantine (Francis Lawrence, 2005)

Under-rated and rarely given the love it deserves, Francis Lawrence’s ‘Constantine’ is more than a $100,000,000 Keanu Reeves vehicle. Featuring a stellar cast (Tilda Swinton, Peter Stormare, Rachel Weisz, Pruitt Taylor Vince), the film also boasts the impressive cinematography of Phillipe Rousselot. An adaptation of the Alan Moore comic ‘Hellblazer’, the continuing saga of a demon hunter named John Constantine.

Constantine, besides sharing initials with the resurrected savior of Christians, has also returned from beyond the veil: having committed suicide in his youth, he went to Hell, and was returned to life where he now hunts hellspawn and yearns for forgiveness. The look and lighting of this film is nothing short of glorious. More than eye-candy, the lighting conveys the director’s intent as well as any other element in the production, including the acting.

Much of ‘Constantine’ takes place at night and, in the scene where Reeve’s and Weisz’s characters are attacked by demons on the street, in almost complete darkness. The cursed nature of Constantine’s existence is echoed in the dim lighting of his apartment, and the gritty shots of the nighttime streets of Los Angeles. These parts of the movie are best described as ‘contemporary noir”and, in a field crowded with similarly styled films, stand heads and shoulders above and go far to conveying the world-weariness of our protagonist.

This is not the only distinctive look Rousselot brings to the film. There are bright, outdoor scenes in the desert and various locations in Los Angeles, cloudless and bright, the polar opposite of the night shots, fiery reds and other hellish tones when he crosses over into the other side, the electric reds and blues of Papa Midnite’s club, and cool blue tones at the climax that echo the poolside setting and the forgiving and fire-quenching nature of water.

Utilizing this constrained palette, Rousselot takes each look to an impressive level. Keanu never looked so ruggedly stylish, Rachel Weisz and Tilda Swinton so fresh, nor L.A. so mysterious.

12. Chinjeolhan Geumjassi (aka Sympathy for Lady Vengeance) (Park Chan-wook, 2005)

There is precious little sunlight in this third and final chapter in Park Chan-wook’s “Vengeance Trilogy”, that bright light light mostly limited to the flashback’s at the beginning and the Australian outback when Geum-ja is reunited with her long-ago adopted daughter.

Except for those latter scenes, taking place far from Korea, daylight is either overcast (the prison yard scenes, her release from prison at the beginning) or ironic (driving to the abandoned schoolhouse through a snowy landscape, Min Chik-soi’s deceptive facade as a normal school teacher).

Punctuated by the sunny reunion with her daughter in Australia, most of the story takes place at night or in dimly lit environments. Dark signifies the evil she struggles against, both to get revenge for herself and her false imprisonment for thirteen years, and for the parents of those kidnapped children Mr. Baek (Min Chik-soi) has murdered.

In fact, as originally intended, Park gradually desaturates the film (aka the “Fade to Black” version) until only the tiniest bits of color remain. Her battle in the alley with two wannabe kidnappers is shot in such low light, that it is sometimes difficult to make out much detail, although this technique works beautifully in ratcheting up the tension. It’s a fine line longtime Park collaborator cinematographer Chung-hoon Chung walks and he does so with the skill and grace of a highwire walker.

13. The Proposition (John Hillcoat, 2005)

Australia is the new Wild West of cinema and its sweeping vistas and arid landscapes are now featured in many films coming from that country. Unable to realize his desire to employ a British or Australian cameraman, director John Hillcoat chose DP Benoît Delhomme both for his work on ‘The Scent of Green Papaya’ and the fact that he is also the camera operator.

Delhomme has stated in interviews that Australia is the star of this film and it is interesting the techniques and restrictions he employed to show his star off to best advantage. Having wanted to shoot a film outdoors, he limited himself to only three focal lengths (citing Henri Cartier Bresson’s use of a only a single lens), avoiding both extreme close-ups and wide shots, and limiting the height of the camera to the director’s requirement of “nothing taller than a horse” in order to keep the look of the film human-sized and period friendly.

His lighting techniques were varied and often employed Fresnel lights to augment the light of the sun, although his main tool was a white sheet placed on the ground. The look he got was surprisingly natural, one example being the scene where Charlie Murphy (Guy Pearce) crosses paths with bounty hunter Jellon Lamb (John Hurt is a singularly inspired performance). By combining Fresnel lighting through the windows and foregoing the use of any interior fills, Delhomme mimics a shadowy bar’s interior in a noon-time Australia to great effect.

To avoid the natural glare of the outback, he adjusted his exposure to match the shadows, or set the exposure so that it would mimic the way one’s retina behaves coming into to a darker space from bright light, almost blinded. For one nighttime shot actually shot day-for-night and tweezed the look through post-processing. The sum total of these processes is a film that leaves you feeling as sunbaked and gritty as the characters you were watching.