14. Dogtooth (2009)

Dogtooth is a purely provocative film, because we aren’t meant to understand what the hell is going on. This unnamed family is so dysfunctional they defy explanation. Father is a brute, forcing his children to perform bizarre tests of mettle, homeschooling them in nonsense, and beating them in inventive ways. Mother is no better, teaming with Father in an unholy partnership of planned parenting.

The children—who are assumedly teenagers—are rewarded with stickers for good behavior, and punished severely for bad behavior. They play masochistic games to fill the time, and lick each other in such nonsexual ways that it becomes more sexual than normal sex.

There is no plot. The closest we have is the eldest daughter’s growing disconcertment with her situation, though this is never vocalized. Instead we learn from her increasingly risky behavior that she must want out of this arrangement. The rest is for our viewing pleasure.

Director Yorgos Lanthimos points his camera nonsensically, capturing people out of frame, holding on characters for no discernable reason. We aren’t in control, and aren’t allowed to know why—just like the children. Dysfunction is cultured in this family, and in the unrelenting brightness filling the white, Greek home in which they live. It is blinding both to our eyes and to our sensibilities.

13. Spider Baby (1968)

Jack Hill’s masterful B-movie, Spider Baby, nearly defies genre. It is a horror film, because the Merrye family bashfully terrorizes any and all visitors to their dusty mansion estate. But Spider Baby is also a comedy, and is just plain odd in the vein of James Whale’s Old Dark House.

While we’re at it, the dusty corpses in the basement evokes memories of Hitchcock’s Psycho, and the quirky murderousness of the Merrye family might even remind us the ghastly family from The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. All of these evocations don’t, however, strip Spider Baby of its originality.

The Merrye family, though of immense wealth, is left to just a few members. Secluded in a giant mansion are two sisters, Elizabeth and Mary, and a brother, Ralph. They are watched over by Bruno, a large, softhearted caretaker. They aren’t actually children, but they suffer from a disease that has doomed them to regress socially and mentally to something like children.

The sisters are ultraviolent lollipop girls, Ralph is sort of like a dog (a sexually violent one), and Bruno is very sweaty, nervous that the house secrets will be found out when a couple of cousins visit, looking to turn the mansion over for profit.

Spider Baby is offbeat horror, the type that doesn’t scare you, but gets into your bloodstream. It’s also funny and weird and unforgettable. The Merrye’s aren’t even so dysfunctional. They just seem so to us outsiders.

12. Capturing the Friedmans (2003)

Capturing the Friedmans follows the story of Arnold Friedman, a computer teacher who, after being caught with child porn, was charged with molesting the young boys in his computer class.

Living in Great Neck, Long Island, there’s not much more for a family to do except fight, but the Friedmans take it to a whole new level. Pitted against her three adult sons, Elaine—the wallowing matriarch of this tightly wound Jewish family—pleads with her husband to turn himself in, which would spare Jesse (the son charged with helping his father in his heinous acts) a heavier sentence.

The remarkable part of Capturing the Friedmans is that much of the footage shown is from home videos filmed by the Friedmans during the lead up to the trial. It is amazing to watch them go at it, the five Friedmans fighting each other, almost as a distraction while staring down the possibility of father and son, husband and brother, going away for the most unthinkable of crimes.

Documentary filmmaker Andrew Jarecki illustrates the story with a sympathetic tone, though where there’s smoke, there’s fire, and where there’s pedophilia, there’s usually jail time.

11. The Squid and the Whale (2005)

Noah Baumbach’s The Squid and the Whale makes reference to the great exhibit at the Museum of Natural History, and it’s not just for use in an anecdote by the film’s central character, Walt Berkman (Jesse Eisenberg), a teenager in 1980s New York City, struggling to cope with his parent’s divorce. Looking at the exhibit says something about divorce, and in this case, the children of divorce look more like the squid, the whale attacking their safety and soundness.

Walt shares the discomfort with his younger brother, but Walt being older, and in high school, brings along a host of hormones and social pressures complicating his ability to deal.

He takes his cues from his father, a once successful writer now falling on hard times (“dad” is played with perfect pretension by Jeff Daniels). His mother (played with equally perfect patience by Laura Linney), a flighty but finally free woman, takes the bulk of Walt’s ire.

Walt’s struggle to come to terms with his mother’s newfound freedom and his father’s glaring imperfections is frustrating to watch. Though Walt is often spiteful and glaringly self-conscious, the light-hearted humor and fast editing gives Noah Baumbach’s third feature a candy-shaped heart—emotional without being cruel.

The Squid and the Whale is thoughtful, bitter, and very funny, often all at the same time. This dysfunctional family is on the precipice of functioning again, albeit fractured. Considering divorce as the final function of a dysfunctional family makes The Squid and the Whale sneakily poignant.

10. The Celebration (1998)

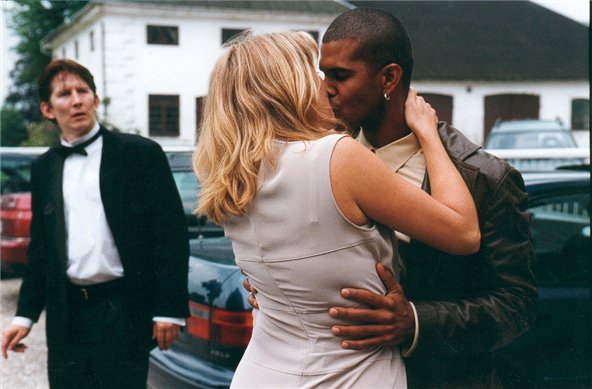

Director Thomas Vinterberg, co-founder of the Dogme 95 film movement, made The Celebration under his (and other co-founder Lars Von Trier’s) strict rubric. What came wasn’t at all an amateurish effort, despite its crude aesthetic. The shaky, erratic, handheld quality served The Celebration’s brisk pace and wild story.

The father of a wealthy Danish family is celebrating his sixtieth birthday with a party at the family’s grand hotel lodgings. But a horrible secret being held by one of his three remaining children (with the fourth having committed suicide not long prior), is about to be exposed, turning their already fragile family completely inside out.

The Celebration illustrates dysfunction at a break neck pace. From the outset, we understand that this family is barely keeping it together. Vinterberg, with little more than a camera in his palm, creates an incredible and nauseating visual experience using some wild camera angles and movements and editing.

The Celebration is funny at times, though just when you want to embrace the humor, you are horrified beyond belief, shocked back to twisted reality. A family this dysfunctional will never recover, but confronting the source at least gives them a chance to breathe easier.

9. Imitation of Life (1959)

Douglas Sirk’s Imitation of Life is a subversive look at the American family unit in the 1950s, though Sirk’s idea of family is progressive in many ways and sharply pointed at the American way of life. Made in 1959, the film focuses on a single-mother with Broadway dreams coping with the reality of caring for her six-year-old daughter. When they meet a homeless black woman and her own young daughter, they hire her as a housekeeper, and a strong bond is forged between them.

Race, motherhood and superstardom come between them, though, and Sirk takes aim at the pitfalls of the American dream while shining a light on the ugliness of racism and material desire.

Nothing drives this point home harder than the daughter of the housekeeper, Sarah Jane, born so many shades lighter that she passes for white. And she is happy pretending, too, much to the disappointment of her mother.

Imitation of Life features four awesome actresses—Susan Kohner, Sandra Dee, Lana Turner and Juanita Moore—four women starring in a film in 1959 (bravo). (For posterity’s sake, see the 1934 version of Imitation of Life, too). There is always opportunity for dysfunction in a family, but with the added pressure of the dysfunctions afflicting American life in 1959 (racism and sexism, here), it is all but impossible for a family to escape it.

8. Interiors (1978)

Woody Allen’s first dramatic effort, Interiors, doesn’t really feel like an Ingmar Bergman film. It pays homage to Bergman, and perhaps the interior scenes and the location—a beach house used for the latter half of the film that reminds us of Bergman Island—are Bergmanesque. But Interiors is a Woody Allen film.

It centers on a family of intellectuals. Three adult sisters must cope with the sudden divorce of their elderly parents. Their mother is a loose cannon, has been unstable for years, and finally now is too much to bear for their father.

One sister is a poet and writer, one an actress, and the other struggling to find a creative outlet. Like many Allen films, trouble boils inside these otherwise successful people. But unlike almost every other Woody Allen film, Interiors is a comedy vacuumed of its jokes.

The whiny one-liners and exhaled humor of Allen’s other auteur efforts—Hannah and Her Sisters, Manhattan, Annie Hall, and Husbands and Wives, to name a few—feels like it has a place in Interiors, and sometimes you’ll laugh without being prompted at this dysfunctional clan of intellectuals. If being smart means being this fucked up, all the more reason to put the book down and flip on the television.