7. Happiness/Life During Wartime

Todd Solondz’ Happiness, like many of his other films, is completely messed up. It pushes the boundaries of provocation, laced with humor to help the medicine go down, exploring taboo subjects with the giddiness of a child rifling through Halloween candy. Solondz explores one family’s struggles to find happiness (as well as some other characters tangentially related).

A woman’s husband realizes his pedophiliac desires, her sister chases degrading sexual encounters, and their other sister stays unwholesomely optimistic after a litany of embarrassments. All of this goes on while their parents decide to separate while living out their golden years in a condominium in Florida.

Solondz takes his characters as far into their personal hells as we think he can go, and then he lingers there. It’s not just for shock value. Solondz is deeply committed to his characters, forcing us to consider them as people beyond their atrocious or pathetic behavior, even asking us to understand not only their pain but to see ourselves in them. Happiness leaves us with nothing resolved, but we’re relieved to be away from it.

That is, until Solodnz made Life During Wartime. Though different actors are used for the characters, Life During Wartime picks up where Happiness left off. The three sisters are followed as their lives have moved on. One sister’s ex-husband, the pedophile fresh out of jail, tracks down his now college-aged son to reconnect, while she is busy remarrying, hoping to God the new one’s not fucked up, too.

Another sister, who, after driving one boyfriend to suicide in Happiness, gets married, realizes she has a similar affect on her new husband, too. Just like we cannot escape them, this dysfunctional family cannot escape its dysfunction, doomed to torment for as many films as Solondz deems necessary.

6. The Ice Storm (1997)

Ang Lee’s The Ice Storm focuses on two families, intertwined in their dysfunctional ways. The Hood’s live next door to the Carver’s. Mr. Hood (Kevin Kline) is sleeping with Mrs. Carver (Sigourney Weaver), the young Hood girl (Christina Ricci) is messing around with the equally young Carver brothers (Elijah Wood and Adam Hann-Byrd), and Mrs. Hood (Joan Allen) and Mr. Carver (Jamey Sheridan) are stuck pretending everything is fine.

Then there is the teenaged son of the Hoods (Toby Maguire), coming home for Thanksgiving, living his own life at boarding school, and yet just as sexually deviant as the rest of his family.

Stuck in the cold Connecticut suburbs, a brutal ice storm impending, the members of the two families try to work out their personal dysfunctions, too self-centered to address their familial ones.

The Ice Storm takes place in 1973, and if the 60’s were a cultural rainstorm in America, Lee is depicting the 70’s as being what has frozen over. The Ice Storm is an emotionally chilling experience. The characters lack concern for each other, the elements are unforgiving, and the elements of the film—sound, shots, editing—nurture uneasiness.

The Ice Storm is a call for familial decency in an age of rebellious overload, forcing the sexually free adults of post-1960s America to look themselves in the mirror, and to look loved ones in the eyes.

5. American Beauty (1999)

Sam Mendes’ American Beauty is a not-so-subtle look at what bubbles beneath the façade of the suburban family.

Life for the Burnham family is chokingly American—real-estate, cubicles, cheerleading and suburbia. When a new family moves next door (even more American in an outdated, sadder way), their lives are thrown into upheaval, existential crises afflicting everyone.

Lester Burnham is played by Kevin Spacey and Carolyn, Lester’s wife, by Annette Bening. These two great performers go at it, and every other performance revolves around theirs.

Mirrored in the tension of the neighbors next door—The Fittses, comprised of an intensely homophobic retired marine, his shell-shocked wife, and their emotionally scarred son—the meltdown of the Burnhams gives the phrase “don’t let life pass you by” paranoid immediacy.

Caught in the middle are the children, Jane Burnham (Thora Birch) and Ricky Fitts (Wes Bentley). Jane and Ricky come together under the guise that they are too different to be properly understood, that their parents are lunatics, and everyone else is just ordinary. Ricky loves to film things using a handheld camera.

American Beauty is made forcefully poetic (unfortunately bordering on poeticism) by Ricky’s films within the film. Even through these two characters, struggling so hard to be different, we see more of the same discontentment—American Beauty is about the dysfunction creeping in all of us, festering inside our plastic family homes.

4. Through a Glass Darkly (1961)

Bergman’s atmospheric drama about a family dealing with the mental illness afflicting one of their own wraps around you like a straight jacket.

The minute cast—only four characters are involved: the writer/father, David, his ill daughter, Karin, his young son, Minus, and Karin’s husband, Martin—and the secluded location (shot on Bergman Island) traps us like bats in the belfry. Bergman’s expert lighting and use of shadows brings Karin’s descent into madness to greater depths, as well as alluding to the darkness hiding inside of David.

Like Bergman’s Cries & Whispers (another family drama centered on illness), when it gets bad, it gets really bad, and it’s hard to get Karin’s wails of torment out of your head. It’s even harder, however, to see David the same, knowing that Karin’s suffering means more to him than just pain.

3. Life is Sweet (1990)

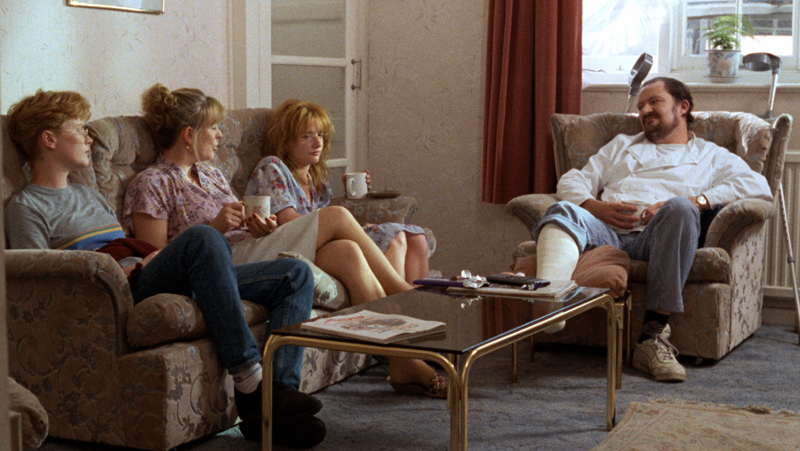

Laughter is the best medicine, especially when confronted with life’s disappointments, chief of which is trying to sweeten a bland existence. In Mike Leigh’s Life is Sweet, Andy and Wendy are trying to make the best of things while living in Northern London with their twin daughters, Natalie and Nicola.

Mike, a working class chef, buys a rusty snack cart from a slick friend, Wendy struggles to see the brighter side of life for her and her family, Natalie is a plumber and happy enough, and Nicola is a nervous wreck struggling with having a bad attitude on top of an eating disorder.

Life is Sweet is about the average dysfunction of working-class family life. Director Mike Leigh seems to be saying that through all the dysfunction there is a brighter side, though getting there requires resiliency and good faith. The trick to life is to pretend it ain’t so bad, but Life is Sweet actually gives credence to this piece of rubbish advice.

With a wonderful cast (including an amazing performance in a side role by Timothy Spall), Life is Sweet balances its comedy with its bitterness, occasionally dipping into hopelessness, but ultimately keeping a smile on.

2. The Magnificent Ambersons (1942)

The controversy over Orson Welles’ second feature film, The Magnificent Ambersons, is well documented. With heavy editing capped by an altered ending by RKO Studios, Welles all but denounced it, claiming it would’ve been better than Citizen Kane had it not been for the meddling studio heads.

Whatever might’ve been, what we have in the only version of The Magnificent Ambersons alive is a prescient look at the effects of industrialization on a wealthy family failing to change with the times, crumbling under the weight of their own ego, especially that of the brattish George, the heir to the Amberson throne. Though technically his last name is Minafer (after his father), George clings to his Ambersons roots like a dog to a chew toy.

Welles took particular joy in showing a wealthy family rotting away—creating one of his most beautifully and sharply shot films ever. You can see every design in the wallpaper in the background, every groove in each statue, all the pieces in the stained glass windows. Welles dazzles us with superficial excellence and Shakespearian romance.

George’s mother loves a man of industry (bringing the world the automobile), and George loves the man’s daughter, though he’d rather lose her to see his mother lose him than allowing cupid his arrows.

Such is the self-combustive stubbornness of a young man out of touch with the world. The dysfunction of the Ambersons clan begins and ends with George. Welles said the success of the film rests with George receiving his comeuppance, and though the studio changed the ending to finish on a happier note, The Magnificent Ambersons is still a marvel and a must see. Families have it hard enough, but when the golden boy, the only child, is a big baby even as an adult, there’s little hope for happy times.

1. The Royal Tenenbaums (2001)

Wes Anderson’s explosive third feature is full of energy and delight. It isn’t always smooth—the overuse of pop music and quirky costumes fit poorly with its forcedly dark overtones against its silly humor. But The Royal Tenenbaums is ultimately a breathtaking film.

Royal Tenenbaum—the rascally, selfish and deceitful patriarch of the prodigious Tenenbaum family—returns seeking his family’s forgiveness as he finds himself broke and desperate. Only he must lie to get back in their good graces.

The Royal Tenenbaums is about the dysfunction of a family that has suffered the wrath of a bad dad. The children, now grown, are terribly unhappy. Yet they are all geniuses, as this fact is reminded to us over and over (ad nauseam).

Elaborate sets and intricate details adorn Anderson’s early magnum opus, and a particularly amazing ensemble cast—a staple of Anderson’s films—helps up the esteem. Gene Hackman, Anjelica Huston, Gwyneth Paltrow, Ben Stiller, Luke and Owen Wilson, Bill Murray and Danny Glover (with Alex Baldwin narrating) makes up the cast, and it’s hard not to enjoy their committed performances.

But it is in Anderson’s filmic exuberance that The Royal Tenenbaums has found its place on the mantel of the most memorable post-millennial films. Creating dysfunctional families is a large part of Anderson’s early catalogue, and yet he never did it better, or with more style and thoughtfulness than in The Royal Tenenbaums. Sometimes a dysfunctional family still loves each other, and so it is only right to remember the good times, burying the bad ones and putting flowers on top.

Author Bio: Jules is a former fiction writer turned cinephile, working towards a career in film criticism. He has a podcast (with a cohost), entitled “Gooble Gobble,” dedicated to the weird, unknown and forgotten films hiding in the catalogues of streaming services like Netflix (coming out on iTunes and www.gobblepod.com Spring/Summer of 2015).