8. Ostře sledované vlaky (Dir. Jiří Menzel, 1966)

Eastern European countries have a history of grotesque culture (in terms of characters and stories, not in terms of quality). Menzel’s brilliant, and politically charged, Ostře sledované vlaky (Closely Watched Trains) examines the explosive life of a station agent (Václav Neckář) whose love life proves to be his undoing, especially when pitted against the oppressive regimes that control his city. The film became one of the staples of the Czech New Wave and helped Czech filmmaking penetrate into an international platform.

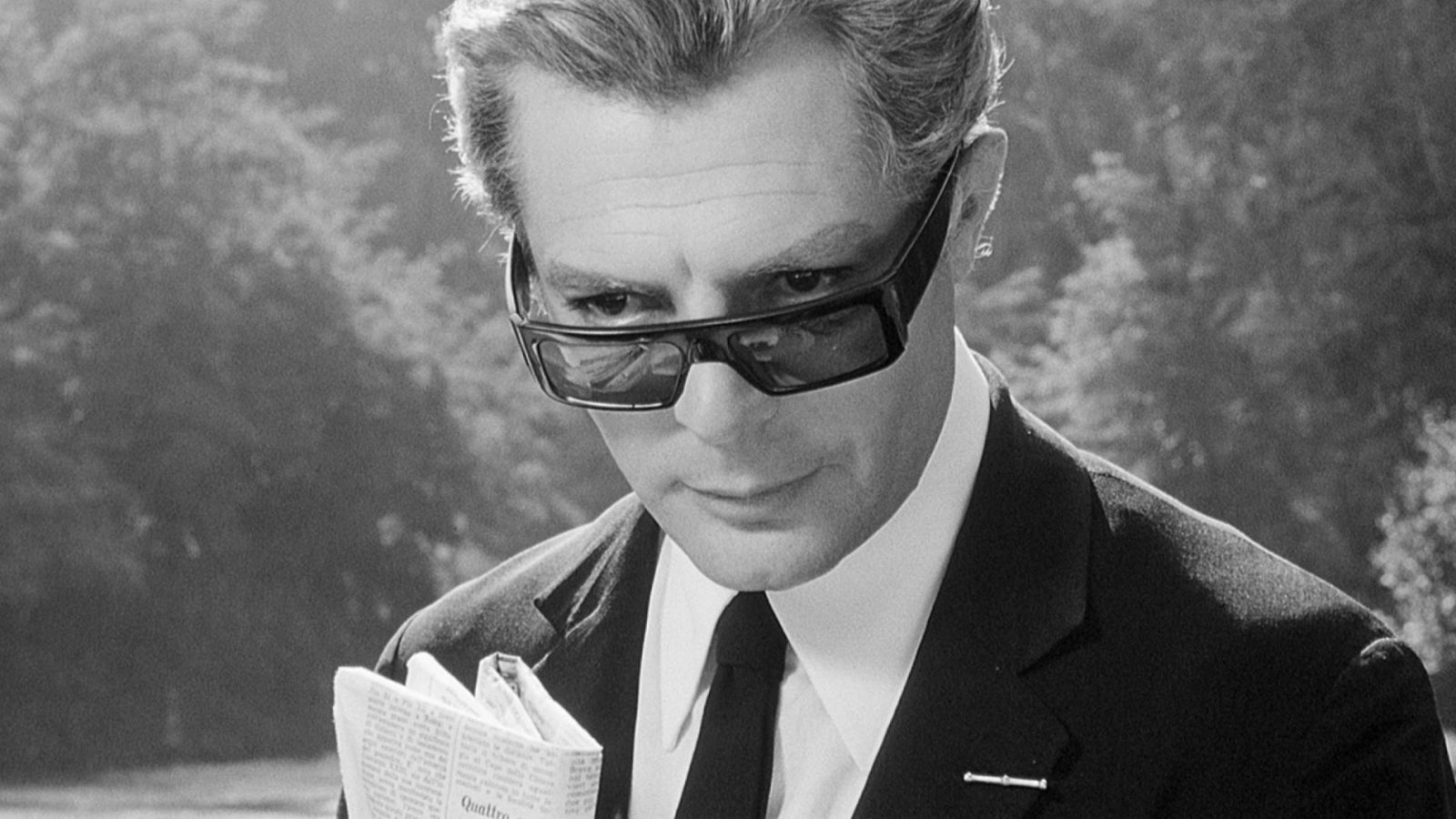

7. Z (Dir. Costa-Gavras, 1969)

The assassination of Grigoris Lambrakis (Yves Montand) shocks a community, and leaves a photojournalist and an investigator to try to put the puzzle pieces together. The tense thriller uses rapid editing by Françoise Bonnot and pulsating music by Mikis Theodorakis to tell the story of political intrigue and corruption. Z uses its energy to both investigate political power and corruption, while simultaneously reinventing the cinematic experience. The film never backs down from its bleak tone, but it does offer one glimmer of hope through its final slogan: “Z – Il est vivant (he lives)!”

6. La strada (Dir. Federico Fellini, 1954)

Sold to a traveling sideshow run by the brutish strong man Zampanò (Anthony Quinn), the naïve Gelsomina (the ever-charming Giulietta Masina) endures personal tragedy all the while meeting a host of sympathetic characters. It is a story told through a neorealist lens, but wrapped in the gargantuan fabric of circus culture (an aesthetic that Fellini would repeat in many of his future works). Though Fellini initially achieved international success with his screenwriting efforts, La strada helped showcase his talent as a director and brought him to the forefront of post classical and modernist cinema.

5. Le charme discret de la bourgeoisie (Dir. Luis Buñuel, 1972)

It is only natural that one of Buñuel’s critical and commercial successes is a film that attacks social structure through food. Le charme discret de la bourgeoisie (The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie) follows a group of bourgeois friends who, for one reason or another, are incapable of having a meal. The film devolves into a series of episodic vignettes, dreamlike trances, stories without end, and hilarious sight gags. The success of the film not only put Buñuel into a mainstream/international discourse, but it helped the filmmaker get a carte blanche for his next (and final) films.

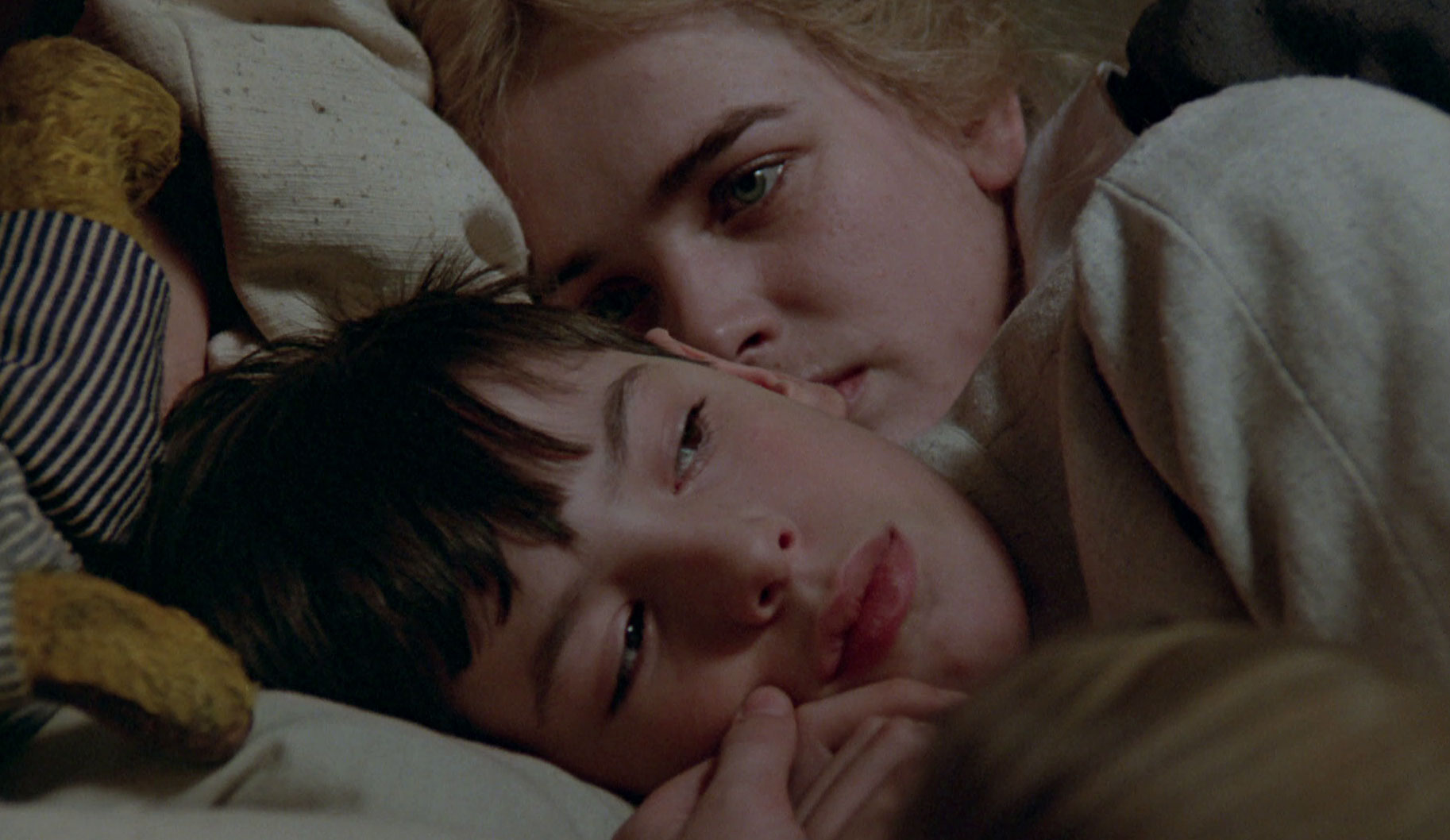

4. Fanny och Alexander (Dir. Ingmar Bergman, 1982)

Following the sudden death of his father, Alexander (Bertil Guve) endures the emotional and psychological abuse of his stepfather (Jan Malmsjö), a local bishop with a penchant for sadistic punishments.

Like many of the filmmakers and films on this list, Ingmar Bergman used Fanny och Alexander (Fanny and Alexander) as a means of untangling his own demons and psychological scars. Alexander represents Bergman, and the bishop represents all that Bergman came to fear: religion, punishment, death, etc. Shot by the masterful cinematographer, Sven Nykvist, Fanny and Alexander juxtaposes its lush settings against its minimalist interiors, constructing a story that both visually and thematically reveals the weight of the emotional and psychological baggage that people carry with them.

3. 8 ½ (Dir. Federico Fellini, 1963)

In the pantheon of self-reflexive films, 8 ½ reigns supreme. Suffering from his own writer’s block following the critical and commercial success of La dolce vita, Federico Fellini couldn’t come up with his next film. His struggles were parlayed into the basis of his next work in which a director named Guido (Marcello Mastroianni) confronts his past, his demons, his lovers, his neuroses, and his crippling creative stagnancy. The film spawned provocative imagery (the opening and closing scenes are brilliant) that still echoes throughout the many films that followed.

2. Ladri di biciclette (Dir. Vittorio De Sica, 1948)

Antonio (Lamberto Maggiorani) finally finds employment by hanging posters, but when his bike is stolen, his job and morality are thrown into crisis. Told through gritty images and brilliant mise-en-scène (which often pits its impoverished characters against the glamour of Hollywood or against the upper classes), Ladri di biciclette (Bicycle Thieves) came to be one of the primary examples of the Italian Neorealist movement. The film, which is often studied in film theory classes, still stands as one of the finest films ever made.

1. Rashomon (Dir. Akira Kurosawa, 1950)

A rape and murder lead to four accounts by a criminal, a deceased husband, a rape victim, and a bystander. A simple story, but in the hands of Akira Kurosawa (whose script was based on the short stories of Ryunosuke Akutagawa), Rashomon came to be known as an important landmark in filmmaking.

It challenges the notion of narrative and perspective, as no two stories are completely the same. It tests the credibility of these fabricated images, while also creating a lasting image of humanity in a modernizing world. The influence of the film is far reaching, spawning similar iterations while also influencing screenwriters to experiment with their own narratives and stories.

Author Bio: Jose Gallegos is an aspiring filmmaker with a B.A. in Film Production/French from USC and an M.A. in Cinema, Media Studies from UCLA. His main interests are the French New Wave, Left Bank Cinema, and Spanish Cinema under Franco. You can read his film reviews at nextprojection.com and view his film poster collections at discreetcharmsandobscureobjects.blogspot.com.