17. Terence McDonagh – Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans (2009)

Nicholas Cage has given MANY crazed performances throughout his wildly unpredictable career, but it’s in this film that the Oscar-winner reaches perhaps peak insanity (and keep in mind, that’s including films like Vampire’s Kiss and the remake of The Wicker Man). This is not necessarily a criticism, as this film is actually quite… well, maybe “good” isn’t the right word, but it’s certainly entertaining and worth watching.

Directed by the always interesting Werner Herzog, the movie actually has little in common with the depressing 1992 Abel Ferrara arthouse film of the same name starring Harvey Keitel (which Herzog claims to have never even seen) beyond having a deeply flawed, gambling, drug addicted police officer as a protagonist. This film takes place in post-Katrina New Orleans (hence the subtitle) and involves a pretty standard murder investigation plot.

With Herzog and Cage combined, however, the result is anything but standard – case in point: the surreal (and brilliant?) tangential sequence consisting of extreme close-ups of a pair of lizards for nearly TWO MINUTES. Though the quality of the film is debatable and may hinge on your tolerance for weirdness, when you’ve got Cage at his Cage-iest, it’s impossible for the outcome to be boring.

16. Oskar Schindler – Schindler’s List (1993)

The true story of Oskar Schindler, played beautifully here by Liam Neeson, is indeed remarkable. Considering where Schindler’s story starts and ends, progressing from Nazi Party member and war profiteer to ultimately saving the lives of more than a thousand Jews, it’s one of the most moving tales of shifting morality told through the medium of film.

Steven Spielberg’s over three-hour long magnum opus paints Schindler as a complex and ultimately unknowable figure. He is clearly no saint – not just as a Nazi, but also as someone who indulges in his own greed and lust during one of the darkest chapters in human history – but as the war continues, his priorities gradually change.

A key turning point is the celebrated sequence in which he witnesses the brutal liquidation of the Kraków Ghetto, focusing pointedly on a young girl whose red coat is one of the only uses of color in this otherwise black-and-white film. Seeing the killings and destruction firsthand is undeniably transformative for Schindler, but his complete change in attitude cannot be attributed to any one moment.

Rather, Neeson plays Schindler with a subtlety that is tough to read at times, though the scene in which he tries to convince Płaszów commandant Amon Goeth (Ralph Fiennes) to spare the lives of prisoners by appealing to his psychopathic egotism is particularly informative. Schindler knows how to play people, and it is this skill that sustains him through the war, and ultimately aids him in doing the right thing and helping create the life-saving list of the title.

A testament to the dangers of apathy and collaboration, especially when conforming to both is lucrative, the film succeeds (among many other ways) in portraying a complicated man whose motivations remain enigmatic, which is far more interesting (and factual) than if Schindler were a one-dimensional good guy operating amidst a sea of genocidal Germans.

The scene at the end when he finally breaks down, admitting that he could’ve done more, is heartbreaking in its honesty, allowing us to see, however briefly, the terrible realizations that can haunt even the best-intentioned among us in retrospect.

15. Sonny Wortzik – Dog Day Afternoon (1975)

Taking place over a mere matter of hours and based on a bizarre true story, this film features one of Al Pacino’s best performances. Heavily improvised, Sidney Lumet’s film stars Pacino and John Cazale (one of the only five films the latter starred in – all of which were nominated for Best Picture – before his premature death from lung cancer) as a pair of amateur bank robbers. The plan quickly goes awry and becomes a hostage situation and media circus. “And it’s all true,” as the film’s tagline states.

Perhaps best known for the “Attica! Attica!” chant (which was ironically an ad-lib), Pacino’s performance is far more nuanced and memorable than for that one scene. The actor purportedly slept sparingly and ate little to simulate his character’s exhaustion, communicating Sonny’s desperation throughout the ordeal.

In a notable example of truth being stranger than fiction, the eventual reveal of the motivation for the attempted robbery makes the whole event even more fascinating. The film stands as both a time capsule of ‘70s era New York City and a showcase for Al Pacino’s tremendous acting talent.

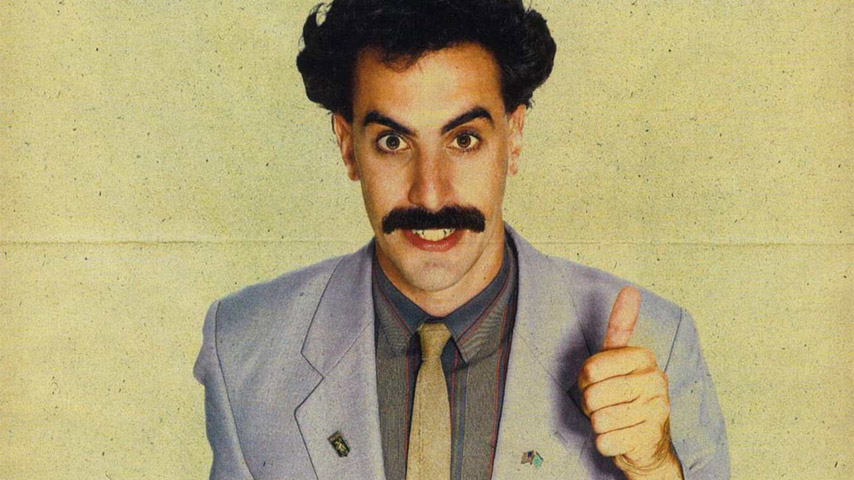

14. Borat Sagdiyev – Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan (2006)

First off, yes, that is indeed the full official title. Of all the alter-egos created by English comedian Sacha Baron Cohen, the fictional Kazakh journalist is easily his best (for further evidence, his outrageous but ultimately miscalculated follow-up, Brüno, comes up short in contrast). Cohen succeeds in making us root for Borat as he travels across the “U.S. and A.” with his faithful producer, Azamat Bagatov (Ken Davitian), on a quest to woo Baywatch star Pamela Anderson, despite the character’s blatantly anti-Semitic, misogynistic, homophobic tendencies.

What makes Borat such a hilarious and subversive film is its mixture of both the scripted and the genuine. While the opening and closing scenes in Kazakhstan and the climax involving Anderson are all scripted, it’s the bulk of the film’s brisk 84-minute running time that makes it an instant classic.

Cohen literally convinces real people that he’s not acting (a feat that should have garnered him an Oscar nomination without question), often causing them to expose their own prejudices as he gleefully spouts the most offensive beliefs imaginable without seeming to realize it.

It’s unsurprising that the film was controversial, resulting in lawsuits and bans galore (not to mention the police being called nearly one hundred times during the film’s production). Cohen’s dedication to the character never wavers, and in fact continued into the film’s marketing (when asked by one talk show host about the charge that the film was anti-Semitic, the Jewish Cohen, in character, replied, “Thank you very much!”).

Of course, there are those who argue that the film doesn’t hold up to repeat viewings, or that the editing made the American public seem far more bigoted than it actually was/is, but there’s no doubt that the film remains a landmark in comedy. It uses daring techniques that, while at times shocking or gross, nonetheless resulted in belly laughs across the world (at least in the places it was legal to watch, that is).

13. Antonio Salieri – Amadeus (1984)

Let’s get this out of the way: Despite the claim in the film’s tagline that “…Everything you’ve heard is true,” Miloš Forman’s Best Picture-winning adaptation of Peter Shaffer’s stage play is not a definitive account of the life and death of Mozart. Rather, it should be taken more as a work of historical fiction, albeit one that is beautiful to look at, listen to, and is, above all, highly entertaining.

While the main subject of the film is, as the title suggests, the (arguably) greatest musical genius of all time, the protagonist is actually the bitter Salieri, a contemporary of Mozart’s whose jealousy of the prodigy was, the film argues, the motivation for a scheme that resulted in the latter’s death.

F. Murray Abraham endured hours in the makeup chair to play the aged version of the Italian composer, who describes the events of the film, shown in flashback, to a young priest after attempting suicide out of guilt. Tom Hulce is equally outstanding as the gifted but vulgar Mozart, whom he portrays as both immeasurably talented and incongruously immature.

Again, while the story’s depiction of the relationship between Salieri and Mozart isn’t that historically accurate (while the two were at times rivals in real life, they had a professional respect for one another, and Mozart likely succumbed, tragically, to an infection of some kind), it is still spellbinding.

Anyone who has ever worked hard for years at something he or she wanted more than anything, only to watch as someone seemingly less deserving achieved the same with little effort, can effortlessly relate to Salieri’s spiritual struggle. It’s an impressive performance that makes us understand and feel for the man while simultaneously condemning his actions.

12. John “Scottie” Ferguson – Vertigo (1958)

The fourth and final collaboration between James Stewart and Alfred Hitchcock, this classic met with mixed reviews and disappointing box office receipts when first released. Today, of course, it is considered a cinematic work of art, topping the British Film Institute’s Sight & Sound poll in 2012 as the greatest film of all time.

In addition to its notable innovations, such as the disorienting “dolly zoom” and an extended wordless sequence early in the film, Vertigo is also a project that had the audacity to make Jimmy Stewart unlikable. Adapted from the novel by Boileau-Narcejac, the plot concerns an acrophobic former police detective hired to investigate the strange behavior of an acquaintance’s wife, played by Kim Novak.

While the story is indeed involving and the choice to reveal its twist much earlier than in the source material was astute, the plot itself is not what gives the film such cinematic importance. Students of film will note that its themes indicate a large amount of self-reflection on Hitchcock’s part, as personified by Scottie’s molding of his love interest to resemble the appearance of another, much as Hitchcock shaped and sculpted his usual blonde heroines.

Enhanced by a resonant score by Bernard Herrmann (without a doubt one of his best), the film’s exploration of the idea of obsession is powerful and haunting, no more so than in the downer of an ending. Though Hitchcock blamed the film’s mediocre critical and financial results on Stewart “looking too old” for the part in hindsight, Stewart’s bold and uncharacteristically less than heroic performance as Scottie is easily one of his best.

11. Mark Zuckerberg – The Social Network (2010)

Again, here is another example of a film that, while based on a true story, could never be confused with being a documentary (not that that’s necessarily a bad thing). David Fincher directed this adaptation of Ben Mezrich’s The Accidental Billionaires, which tells the story of Mark Zuckerberg and the creation of Facebook.

With a crackling screenplay by Aaron Sorkin and a pulsating score by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross (both of which won Oscars in their respective categories), the tone is decidedly dark, especially for a story with no fatalities.

Jesse Eisenberg gives an icy and intense performance as the computer prodigy whose invention would make him one of the youngest billionaires in the world. Of course, the real Zuckerberg disputed the film’s accuracy, citing the portrayal of his motivations for creating the website in particular, though granting that the film got his wardrobe exactly right.

Regardless of how true the film version of the story is, it nevertheless provides a consistently entertaining illustration of what it takes to achieve the American dream, and the fallout – both positive of negative – of reaching that goal. Who would have thought that a movie about how a computer wiz made one of the world’s most popular websites would have garnered comparisons to Citizen Kane?

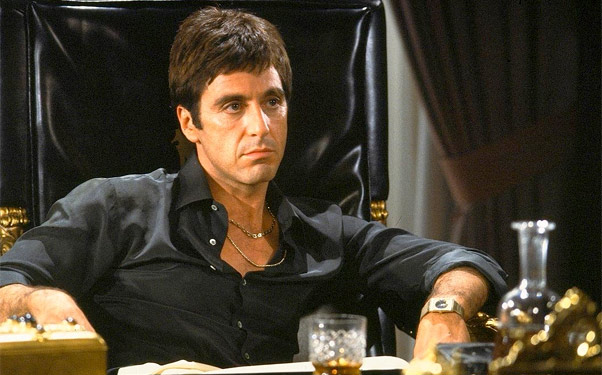

10. Tony Montana – Scarface (1983)

Many may not realize that Brian De Palma’s gangster classic is actually a remake of a film made fifty years prior, though on the surface the two seem pretty different. The 1983 film features graphic violence and wall-to-wall profanity, in fact setting the record for most uses of the word “fuck” and its derivates at the time (just try watching the censored version on basic cable – it’s both impressive and hilarious). That said, the shock value is hardly the only aspect of the film that makes it noteworthy.

Written by Oliver Stone in the midst of an admitted cocaine addiction, the film tells the story of fictional Cuban refugee Tony Montana, who comes to Miami during the Mariel boatlift of 1980 and proceeds to build a drug empire. Pacino has stated that Montana, whom he plays with a thick accent, is one of his all-time favorite roles, and it’s not hard to understand why.

The character is so over-the-top that decades later he’s still weirdly emulated to a degree in certain circles, influencing the worlds of hip hop and video games. And while the climactic line, “Say hello to my little friend!” is likely the most memorable one in the film, it’s just one of many violent, but yes, fun parts in this unapologetic and epic crime saga.

9. Harry Callahan – Dirty Harry (1971)

Clint Eastwood has made a career out of playing outlaws and heroes of questionable morality, but it’s the role of Inspector “Dirty Harry” Callahan for which he’ll possibly best be remembered (in terms of his acting performances).

The star of a franchise of five films, “Dirty Harry” was first introduced in the 1971 Don Siegel film of the same name. With his trademark .44 Magnum and a host of badass lines and catchphrases (some of which are often misquoted), the character has become something of an icon, influencing nearly every “cop who plays by his own rules” movie made since.

In the first film, Harry faces off against a serial killer modeled on the Zodiac Killer who calls himself “Scorpio.” Clint perfectly embodies the character, making him both cool and unpredictable. Present-day San Francisco works as a logical progression from the desert expanses of the Wild West audiences were accustomed to seeing Clint in up until this time, making his Harry a modern cowboy of sorts.

Along with Straw Dogs and A Clockwork Orange (both released the same year), the film helped usher in a new era of acceptable levels of violence in cinema. Perhaps partially the result of the chaotic turmoil of the ‘60s and the Vietnam War, these films likely appealed to viewers who wanted to live vicariously, watching as fictional heroes and villains played out their collective anger in a bloody but harmless manner.