8. William “D-Fens” Foster – Falling Down (1993)

“I’m the bad guy?” This is the sad, key line in Joel Schumacher’s excellent and incisive film about a divorced, unemployed former defense worker who rampages through L.A. on a journey (by foot, no less) to his young daughter’s birthday party. Michael Douglas plays our antihero – so nicknamed because of the license plate on the car he abandons in the traffic jam that opens the film – as a man who’s simply had enough and decides to take his repressed rage at society out on all who get in his way.

The film was not without controversy, angering some over its depiction of minorities, defense engineers like the Douglas character, and typifying the stereotype of the “angry white man.” It could never be called thoughtless though. Douglas says this is his favorite performance of his career, as the character is far from a maniac. He’s portrayed both as villain and victim, his actions stemming from relatable grievances, yet being impossible to condone.

It’s a film that still resonates today, especially with the current climate of racial tensions in America, as an underrated exploration of what can happen when an already unbalanced individual is pushed just a little too far…

7. Captain Jack Sparrow – Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl (2003)

You’ve got to hand it to Johnny Depp. The famously unconventional actor helped turn a film resulting from the questionable idea of using a Disney theme park ride as its basis into one that started a multi-billion dollar grossing franchise. With four films released so far and a fifth on the way, the first is still unquestionably the best, and the only one to earn an Oscar nomination for acting (Depp’s, of course).

Channeling Rolling Stones guitarist Keith Richards (who would later appear himself in the series as Jack’s father), Depp initially worried studio executives with his unexpected interpretation of the character.

Playing Jack as ambiguously drunk and with a series of flamboyant mannerisms to accompany his unique facial hair and makeup, Depp makes the fictional pirate not just fun to watch, but the indisputable highlight of the film. Favoring the use of his head rather than his sword, and even running away at times, he is definitely not your typical pirate.

The Jerry Bruckheimer-produced films may have decreased in quality as time progressed and their budgets ballooned (director Gore Verbinski dropped out after the third as well), but their money-making potential was just too large to abandon.

Luckily, Depp’s continued presence makes them at least watchable, and has even gone on to influence areas of life outside of the films. Indeed, Jack Sparrow has become an extremely popular Halloween costume, and is now considered one of the greatest action heroes in recent film history (despite his often less than heroic behavior).

6. John Rambo – First Blood (1982)

Who would have thought a character named after a variety of apples would be so kick-ass? Based on the novel released ten years earlier, First Blood tells the story of a Vietnam veteran and former green beret who, when harassed by a small-town sheriff, starts a veritable mini-guerilla war in the woods of the Pacific Northwest.

Unlike its source material and its three (as of the writing of this list) hyper-violent sequels, the first film in the Rambo series has a surprisingly low body count. Star Sylvester Stallone, who co-wrote the script, actually toned down the violence and made Rambo more sympathetic, simultaneously changing the meaning of the story. While the unhinged Vietnam vet became a trope following the contentious war, Stallone turned Rambo into an abused and misunderstood warrior rather than a PTSD-fueled psycho.

While the book’s suicidal ending would have deprived the world of the franchise if followed, it may have been more fitting for the grim material. Though it’s difficult to understand, the normally dialogue-averse Rambo’s impassioned monologue at the climax of the film is both heartrending and revealing, satisfactorily explaining his damaged mindset.

Rather than having snapped and gone crazy, he’s simply tired of being unappreciated, shunned, feared, and abused by the country he’s fought to defend. While Rambo’s actions constitute an overreaction, it’s notably understandable from his perspective and given his backstory.

The subsequent films would never explore this message with as much poignancy as First Blood, opting instead of for the high-octane blood, bullets, and explosions approach. This leaves the first film with the distinction of being that rare action film with something important to say – all the more laudable given its close proximity in time to the real war its fictional antihero suffered through.

5. Charles Foster Kane – Citizen Kane (1941)

It’s hard to overstate the influence and importance of Citizen Kane in film history. Required viewing for all film students, this black-and-white masterpiece has been endlessly studied and dissected, frequently appearing on lists of the greatest films ever made, if not occupying the #1 slot. That it failed to win the Oscar for Best Picture has only added to its legacy as a filmmaking milestone that, while admired upon initial release, was not given the proper honors and effusive praise it should have received at the time.

All the more impressive is the fact that co-writer, producer, director, and star Orson Welles was in his mid-twenties when he made the film – a staggering achievement that he’d never top. The character of Kane himself is an enigma, his dying word, “Rosebud,” providing the central mystery of the film.

Modeled not so subtly on newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst, Kane is a ruthless megalomaniac, intent on achieving greatness at the expense of friends and family. The film charts Kane’s life from his impoverished childhood in Colorado to old age (makeup is used to convincingly transform Welles, its effectiveness surprising given when the film was made) in his self-made castle of Xanadu.

At two hours long, the monumental film is hardly a chore to sit through, unlike other singular motion pictures, and offers a gripping story in addition to its constant display of advanced cinematic techniques. And while some may find the revelation of Rosebud’s meaning to be anticlimactic, it does give us a startling final bit of context to aid in understanding this complex man.

Welles’s performance and screenplay create a “warts and all” portrait of a person who, while fictional, is nonetheless comparable to many larger-than-life public figures, both past and present. His willingness to show Kane’s vulnerabilities and ugliness in addition to his successes is striking, and one of the reasons the film still holds up today as a dark fictional biopic that demands to be analyzed after being enjoyed.

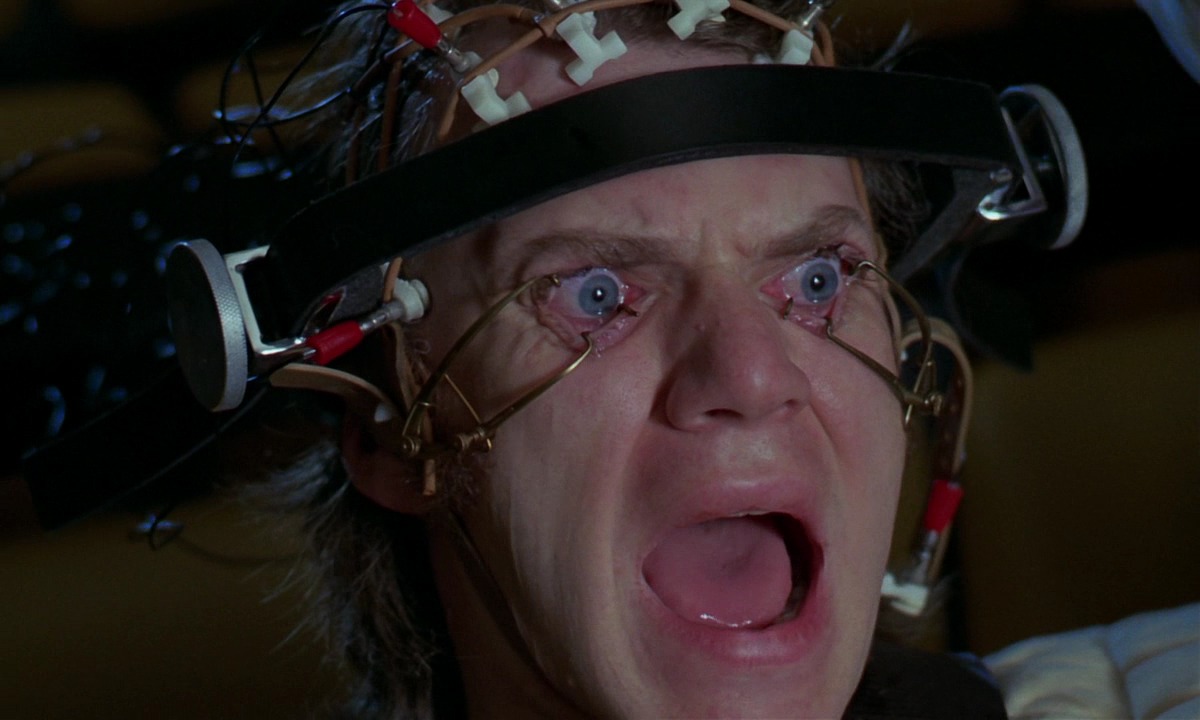

4. Alex DeLarge – A Clockwork Orange (1971)

If “antihero” is defined as someone with a mix of both admirable and terrible traits, than it’s hard to find a better example than Alex, the murderous yet magnetic “humble narrator” of Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 tour de force.

Still controversial to this day (though less so now than it was during Kubrick’s lifetime), the cinematic adaptation of Anthony Burgess’s dystopian novel is a meditation on subjects no smaller than the concepts of good and evil and the issue of how to balance free will with communal protection.

It tells the story of an amoral youth who, after undergoing an experimental new form of aversion therapy in prison, becomes victimized by the society he once terrorized. Played by Malcolm McDowell in a career-making performance, Alex is far from unidimensional. An unrepentant criminal, he leads a gang that, as a form of entertainment, rapes, steals, and assaults whoever is unfortunate enough to cross paths with them in the night.

Surprisingly, however, Alex is no brainless thug. He exhibits intelligence, speaking at times poetically in the fictional slang language invented by Burgess dubbed “Nadsat,” and appreciates classical music – especially that of Beethoven. And while the omitted ending of the book softens his character somewhat, the film has no such interest.

Kubrick does, however, do everything in his power to keep us on Alex’s side as much as possible, being sure, for example, not to focus on literal blood until it’s coming out of Alex rather than his victims. Classical music is used to evoke the joy Alex feels while committing random acts of violence, robbing the carnage of its gritty realism.

McDowell famously suffered for his art, experiencing cracked ribs and scratched corneas during filming. And while we may catch ourselves feeling bad at times for the abused person at the center of this futuristic fable, we can never forget how much of a monster Alex truly is. It’s Kubrick’s ability to blur these usually distinct lines that is part of what makes this decades-old shocker still relevant and powerful.

3. Michael Corleone – The Godfather (1972)

Though simple, the title has deep meaning, echoed in the film’s final line, “Don Corleone.” Marlon Brandon may have won the Oscar for Best Actor (which he famously – or infamously, depending on your perspective – refused to accepted), but it’s really the young Al Pacino who has the full character arc.

Widely considered one of the greatest – if not THE greatest – movie ever made, the storyline is a tragedy worthy of Shakespeare. Adapted from Mario Puzo’s novel by both Puzo himself and director Francis Ford Coppola, the nearly three-hour long film tells the story of the complicated transfer of power from the aging head of an organized crime family to one of his three sons.

Starting the film as a decorated war hero wanting nothing to do with the family business, Michael slowly becomes more involved in his family’s criminal activities after his father is shot and almost killed by rival gangsters.

The pivotal scene in which Michael commits his first murders on behalf of the family is a master class in suspense, the tension brilliantly orchestrated by Coppola through the combined use of precise sound design, camera work, subtitles, and of course, Al Pacino’s great performance (much of it nonverbal).

An epic but not never dull film, The Godfather is a quotable classic featuring one of the most absorbing character journeys ever in film, which continues in the equally stunning – if not even better – Oscar-winning sequel. Far more restrained than in his go-for-broke performance years later in Scarface, Pacino as Michael Corleone is a performance for the ages – an indelible illustration of an individual’s reluctant rise to power accompanied by the loss of his soul.

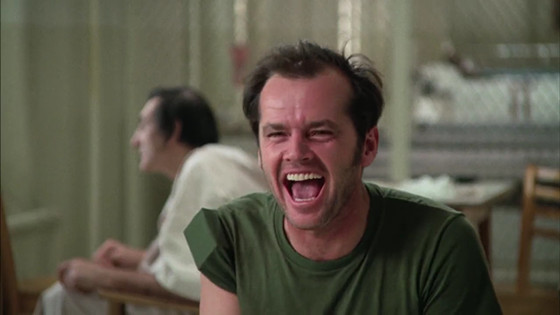

2. Randle Patrick McMurphy – One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975)

Deservedly winning his first Oscar after a series of acclaimed nominated performances, Jack Nicholson is at his manic best here, perfectly cast as the protagonist in Miloš Forman’s adaptation of the 1962 book by Ken Kesey. Kesey eventually would have a falling out with the filmmakers over some of the changes made to the story, but it’s hard to argue with the result: the film went on to win the top five Oscars (Picture, Director, Actor, Actress, and Screenplay), and remains as potent today as it was when first released.

McMurphy is a societal misfit, driven by hedonism and rebelliousness, but he’s not insane. Sent to a mental institution to avoid serving hard time in prison as part of a short sentence for statutory rape, he disrupts the routine order established by the authoritarian Nurse Ratched (Louise Fletcher).

The film calls in to question the notion of insanity, and reveals the extent to which those in charge can grow corrupt and mad with power. It’s impossible not to root for the charismatic McMurphy as he goes from trying to reason with Ratched to resorting to disobedience and eventually outright rule-breaking, as demonstrated during an unscheduled fishing trip he organizes, temporarily breaking his fellow inmates out.

Buoyed by supporting early-career performances from Brad Dourif, Danny DeVito, Christopher Lloyd, and especially Will Sampson as a seemingly deaf-mute Native American mental patient, the film is both uplifting and challenging.

We know McMurphy won’t be able to get away with his behavior forever, but the injustice of how his story ultimately unfolds still disturbs to this day. He’s hardly a model citizen, but McMurphy’s mini-revolution is entertaining to behold as a great fight-the-power story, albeit an ill-fated one.

1. Travis Bickle – Taxi Driver (1976)

The ultimate antihero, the protagonist of Martin Scorsese’s plunge into the darkest aspects of ‘70s-era New York City is unforgettable. Embodied by Robert De Niro (who worked 12-hour shifts driving cabs to prepare for the role), Travis is difficult to pin down.

Screenwriter Paul Schrader has explained that the story is semi-autobiographical and that the main theme of the film is loneliness, he himself having struggled with isolation and social rejection before writing the film. Another big inspiration was the published diary of Arthur Bremer, the man who attempted to assassinate then- presidential candidate George Wallace in 1972.

The behind-the-scenes information is relevant in order to better understand Travis Bickle, whose actions – especially at the end of the film – have often been misunderstood.

The story is simple: Travis becomes a taxi driver to deal with his insomnia (Fight Club, anyone?), only to sink deeper and deeper into paranoia and psychosis after experiencing romantic rejection and becoming disgusted by the rampant crime he witnesses on a daily basis. His chance encounter with a teen prostitute (played by Jodie Foster), along with a political campaign swirling in the area, become the catalysts that cause him to take drastic actions.

In addition to being an excellent character study, this is also a great film about mental illness. What Travis suffers from exactly is never made clear, though some have speculated that his behavior and thoughts bear the hallmarks of schizotypal personality disorder.

Regardless of his diagnosis, it’s hard to minimize the film’s significance in the development of more personal, psychologically-minded and darkly realistic films. There are multiple readings of the ending, and critics have interpreted the film as being about everything from masculinity to urban decay to the traumas of war.

And of course, there is the controversy sparked by John Hinckley Jr.’s attempted assassination of President Reagan (hardly the film’s fault that the movie inspired him, but a troubling association nonetheless).

In the end, Taxi Driver taps into something familiar for many viewers: a growing dissatisfaction with the outside world, especially when compounded with the isolation that can all too often come with living alone in a big city. Travis Bickle may have been crazy, or at least very disturbed, but that doesn’t mean he was necessarily wrong about everything either…

25 Honorable Mentions (listed alphabetically by film):

Lester Burnham – American Beauty (1999)

Jeffrey “The Dude” Lebowski – The Big Lebowski (1998)

Carrie White – Carrie (1976)

Paul Kersey – Death Wish (1974)

Wikus van de Merwe – District 9 (2009)

Bobby Dupea – Five Easy Pieces (1970)

Fritz – Fritz the Cat (1972)

The Man With No Name a.k.a. “Blondie” – The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966)

Henry Hill – Goodfellas (1990)

Steven Jay Russell – I Love You Phillip Morris (2010)

Rupert Pupkin – The King of Comedy (1983)

Humbert Humbert – Lolita (1962)

May Dove Canady – May (2003)

William Lee – Naked Lunch (1991)

Louis Bloom – Nightcrawler (2014)

Seymour “Sy” Parrish – One Hour Photo (2002)

Jake LaMotta – Raging Bull (1980)

Ethan Edwards – The Searchers (1956)

Pasqualino Frafuso a.k.a. Settebellezze – Seven Beauties (1976)

Karl Childers – Sling Blade (1996)

Benjamin Barker / Sweeney Todd – Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street (2007)

Daniel Plainview – There Will Be Blood (2007)

Mark Renton – Trainspotting (1996)

Jordan Belfort – The Wolf of Wall Street (2013)

Randy “The Ram” Robinson – The Wrestler (2008)

Author Bio: Jason Turer received his B.A. from Cornell University with a double major in Film and English, and currently works in TV and film production in New York City. He has too many favorite films to list here, but some of his favorite directors include Kubrick, Cronenberg, Hitchcock, and Lynch.