4. Being There (Hal Asbhy, 1979)

Chance is a gardener who lived his entire life taking care of the plants in a house in the suburbs of Washington, DC. When he is forced to get out into the real world, he knows only what he saw on TV.

But after a series of fortunate events, he is not destroyed and suppressed by society and the outside world. Instead, the major exponents of it want to hear from him about his considerations of the state (of things) and about the State. He will be received by the president himself, who will quote Chance’s words, that are nothing but tutorial to gardening, in one of his speeches.

Hal Ashby makes a perfect satire of society and, generally people, who believe that everything that “is there” on the TV that Chance (a marvelous, both sad and funny, Peter Sellers) watches obsessively, is true and must be trusted and followed. Chance knows everything through TV, but he is somehow superior to everyone who surrounds him and wants to earn from his person (“they” want him to become even president).

Conversely, to a lot of other movies with a similar subject (the “normal person” mistaken for a genius), in “Being There” the mistake is not uncovered, but it may continue forever while Chance himself doesn’t pay attention to it. He walks away upon a lake, without sinking. He is a modern Idiot, laic and religious at the same time (just like in Dostoevsky’s masterpiece). He goes away, careless but not selfish, unconcerned by “human actions”, because he is, somehow, the genius everyone sustains him to be, just in a diametrically opposite way.

3. Match Point (Woody Allen, 2005)

Of all the movies on this list, Woody Allen’s (who has already dealt with Russian literature and Dostoevsky himself in one of his greatest masterpieces, “Love And Death”) magnificent “Match Point” is, without any doubt, the most clearly Dostoevskian. Allen immediately gives us a hint in one of the first scenes, in which the main character, Chris Wilton, reads “Crime And Punishment”.

Just like in one of the two episodes narrated in “Crimes And Misdemeanors”, Allen explores not just the human being, with its selfish thirst of power and wellness (unconcerned for other people’s decline or death), but also the presence of evil in the world and its unintelligible and constant victory against good.

Particularly in “Match Point”, he deals with the importance of luck in our lives and how frighteningly decisive it is for all of us, so much so that it can literally change the course of the events, just like when the tennis ball hits the net and, during that endless moment, it could fall either on one side or on the other. In fact, this is the crucial point of all the movies (and the crucial point for most of the greatest thinkers of history): where does this fortune end and where does our free will begin?

Our “hero” is different from and, at the same time, like Raskolnikov, the protagonist of “Crime And Punishment”. They both end up murdering, also in a very similar way (putting-on a theft), but, while Raskolnikov commits his crime as if it was a moral duty, a need for the society, Chris decides not just to kill for his personal interests, but also to murder a person he loved.

Woody Allen demonstrates also his total lack of hope toward humanity and justice (interpreted both as an abstract object and as an institution) through the reaction Chris has after the murder: his face remains the same, he can talk without hesitation about the killing after having read it in the newspaper, wearing his bathrobe and having breakfast with his wife in their attic in front of St. Paul’s Cathedral.

His conscience is clear, for he thinks he has done something good for him, while Raskolnikov, who really has killed for “good reasons”, is haunted by regret and ends up confessing. Chris will not do such a thing; he will just stay aside, looking at what is happening. Now, “fate” plays its game, saving Chris.

Allen is trying to tell us that it is up to us, up to our free will, to decide to confess, because no one will do that for us, because we deserve our punishment, but we are too evil and miserable to understand that and we will always put ourselves before others, even if this means killing someone else. Raskolnikov is, therefore, a heroic character and an honest person. But modern “heroes” (and persons) are more like Chris Wilton.

2. Rope (Alfred Hitchcock, 1948)

“Good and evil, right and wrong were invented for the ordinary average man, the inferior man, because he needs them,” says Brandon, one of the two murderers in Hitchcock’s terrific movie, sustaining that his intellectual and physical superiority permits him to commit a murder, because “nobody commits a murder just for the experiment of committing it. Nobody except us”. Brandon is the joining link between Chris Wilton, the protagonist of “Match Point”, and Raskolnikov, the main character of “Crime And Punishment”.

“Rope” is, effectively, on this list, the movie that was most influenced by Dostoevsky’s most famous novel. If “Match Point” was the movie in which the Dostoevskian atmosphere was most palpable and evident, “Rope” transforms the major twists and reflections of “Crime And Punishment” into an incredibly mean satire about the upper-class world that, in addition,

Hitchcock turns into an extremely tense thriller, also thanks to the astonishing camera work. The only true difference between the movie and the novel is the motive that leads to the murder. In the book, just as it was already said, the murder is lived as a moral duty; in the film it is just an exercise, something done just to see what is happening and to confirm Brandon’s theory that superior men can and should kill.

This leads us back to “Crime And Punishment” and to Dostoevsky; Raskolnikov thinks he is better than the people around him; and killing those under him is justified and understandable. Brandon says the same, but he is just trying to legitimize his crime and he is trod by someone who, just theoretically, thinks the same things Brandon has the courage to admit.

1. Taxi Driver (Martin Scorsese, 1976)

“I am a sick man… I am a spiteful man. I am an unpleasant man. I think my liver is diseased. However, I don’t know beans about my disease, and I am not sure what is bothering me. […] My liver is bad, well then let it get even worse!” This is part of the incipit of Dostoevsky’s “Notes From The Underground”, in which the anonymous protagonist presents himself.

He observes the world from a metaphorical underground, in which he buried himself alone, hating everything and, at the same time, hating himself more because of this. He is not a child of a primitive society, he studied, he works, he could change his life, yet also when the occasion is literally in front of him in the form of a prostitute, he consciously destroys it, feeling good while doing it, reaching the limit of his abjection and unloading his frustration on a more unsuitable (and undefended) person.

Paul Schrader, the famous screenwriter of “Taxi Driver”, was obviously inspired by this short novel while he was creating the iconic character of Travis Bickle. The analogies are evident. In Schrader’s re-writing, the Vietnam War is also important. Travis is a reject of a society that used him as cannon fodder, and now all that remains is for him to look at the Big Apple that surrounds him from his taxi, by night, when all the rotten parts of humanity can be left unleashed.

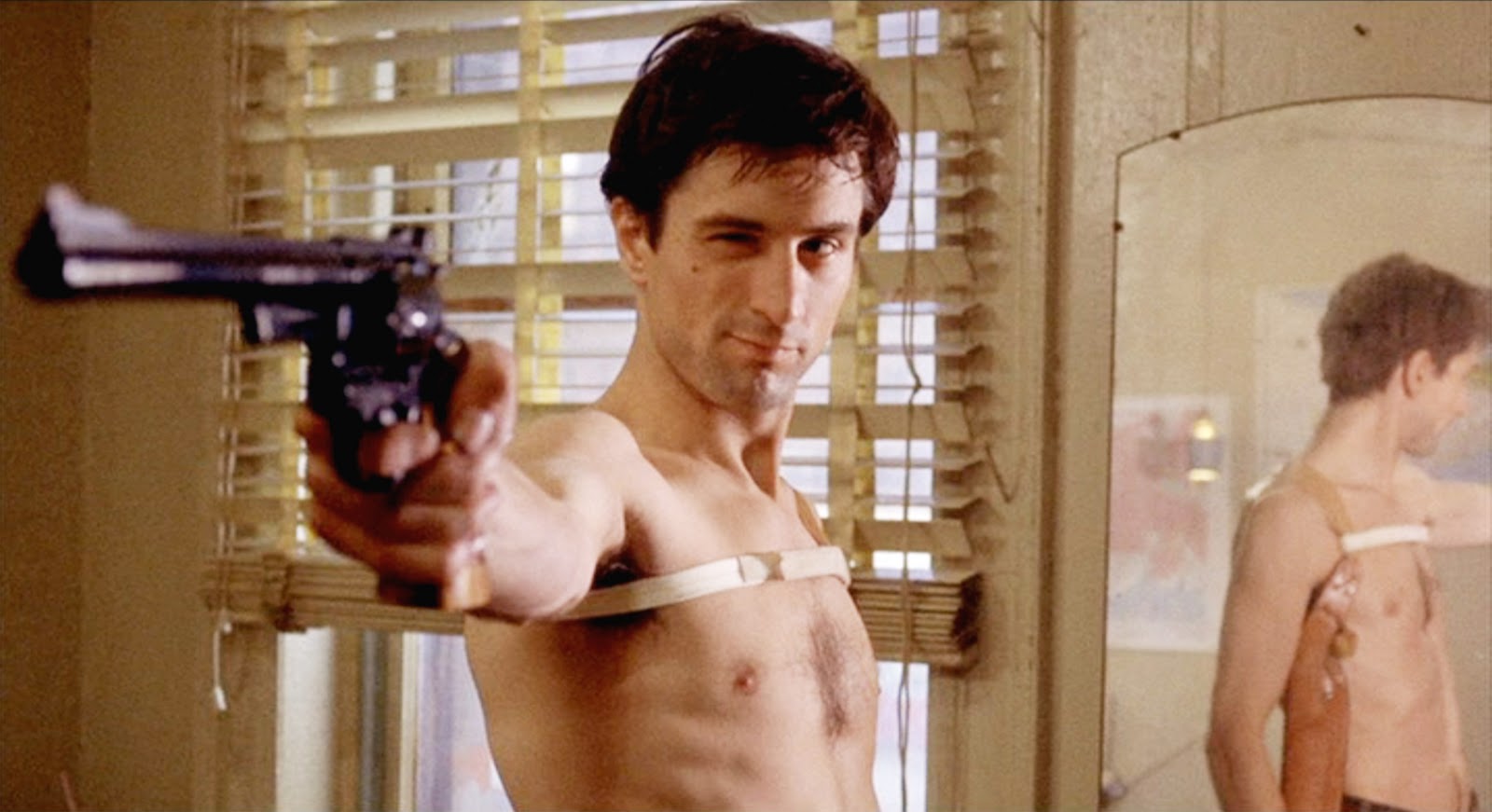

Martin Scorsese brilliantly expresses this confusion and lack of aim in just one, perfect choice of direction; Travis is talking on a public phone, but the camera does a little movement to the right, cutting Robert De Niro out of the frame and leaving it empty, until the phone call is over and Travis walks away, but he is relegated to the extreme left side of the shot and we are able to see just his shoulders.

Unlike the narrator of “Notes From The Underground”, Travis tries to enter the society and, in the end, he ironically succeeds, trying to help Jodie Foster, concluding the first kind impulse that the Dostoevskian anti-hero had while seeing Liza, the prostitute, for the first time. The consequences are extremely sick and realistic, and it is an undisputed masterpiece.

Author Bio: Pietro Mauri lives and studies in Milan, Italy. He collaborates with some Italian movie websites. He writes about cinema because he says, paraphrasing Ingmar Bergman “Cinema is a need, like eating, drinking or sleeping, and every cell in my body is completely imbued with it”.