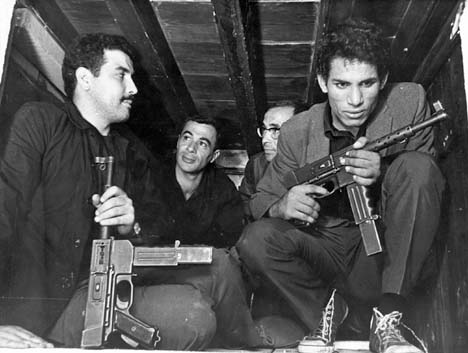

5. The Battle of Algiers (Gillo Pontecorvo, 1966)

The Battle of Algiers is, without a doubt, as technically sound and efficient as movies can aspire to be. It’s been hailed by some critics as one of the best war films to have ever been produced due to the type of fictional realism it employs.

So much so, that back in 2003 it was famously shown at the Pentagon as a complementary lesson for the war in Iraq. Italian director Gillo Pontecorvo conducts every sequence with surgeon like precision and the final result is a carefully crafted cinematic gem that sheds light on Algeria’s fight for independence from France.

To this day the experience gives out a fresh, on the moment type of sensitivity that’s close to hypnotic. The bombings and torture scenes are still pretty impressive as well. Direct, engaging and uncompromising; a must watch for any film student.

4. Lucía (Humberto Solás, 1968)

Three different female characters named Lucía take center stage during three different periods of Cuban history in one grandiose spectacle. In terms of production value this is the most ambitious title on the list: an epic that focuses on Cuba’s twentieth century transitions.

The film’s philosophical blueprint consolidates key aspects of social representation like sex, class and political values which in turn become meshed with a variety of language methodologies that comprise and complete its diagram of practice.

While each segment shares and deals with their respective heroine’s own process of lucidity, none is quite like the other. Nevertheless, the anti-colonialism sentiment is quite palpable all the way through its two and a half hours running time.

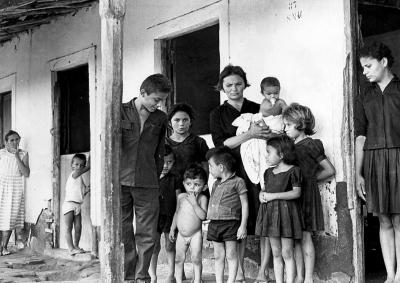

3. Twenty Years Later (Eduardo Coutinho, 1984)

Truth is stranger than fiction and Twenty years later is certainly proof of such an adage. Eduardo Coutinho’s poignant tour de force is the completion of a job left undone that’s both highly personal and historically relevant. In March of 1964 Coutinho had begun directing a fictionalized account based on the real life slaying of brazilian farm leader João Pedro Texeira that was interrupted and ultimately closed down by the military coup d’etat that occurred on the 31st of that same month.

A number of the mainly non-professional actors were imprisoned, others (like Elizabeth Texeira, the widow of João Pedro, who was actually playing herself in the movie) had to go into hiding and nearly all of the filmed material was confiscated.

Coutinho, however, managed to salvage fragments of footage and in the early eighties went back to the same community in hopes of tracing the people he had worked with. The result is an anthropologically rich and emotionally charged experience that is inevitably bound to leave a mark.

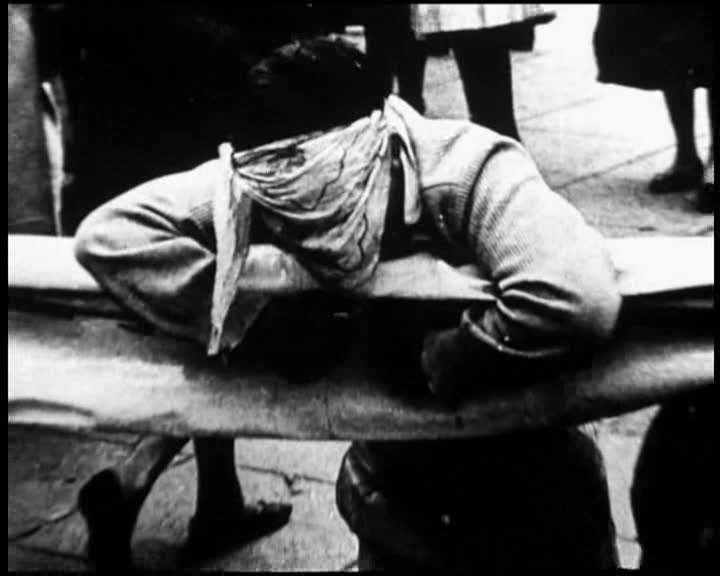

2. The Hour of the Furnaces (Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino, 1968)

Widely regarded as the prime example and crowning achievement of the Third Cinema movement, The Hour of the Furnaces is a 260 minute revolutionary propaganda masterpiece. The movie is divided into three parts that can, in a sense, respectively stand alone for the reason that each develops a particular treatment with varying motifs.

Solanas and Getino use every aspect of film language that they can with the sole purpose of molding them into weapons capable of psychosocial consequence which brings about the vital bombardment on the spectators senses. Though it is true that all works feed off public input, in this case that notion becomes an absolute necessity. Agitation on film has never been so striking.

1. The Battle of Chile (Patricio Guzmán, 1975, 1976, 1979)

There’s a word that comes up almost every time someone refers to The Battle of Chile and it’s: monumental. The reason for this (apart from being divided into three parts that make up a total running time of almost five hours) stems from the fact that, from both a literal and figurative standpoint there is no better way to describe it.

For several months, Patricio Guzmán accompanied by a small crew took to the streets of Chile to capture the sociopolitical pandemonium that ultimately gave way to a savage military coup on September 11, 1973. Structured on a very journalistic vein that entails a more vivid sense of participation from its audience, this awe-inspiring documentary is one of the greatest feats to ever be put on film.

A most serious and commanding work, that manages to rescue a critical portion of its country’s collective memory.

Author Bio: Guillermo is a film critic and screenwriter from Puerto Rico. At times dabbles as freelance audiovisual resource and currently developing an artisanal photography project.